Tel Aviv

Israel

Name of Interviewer: Tanja Eckstein

Date of Interviews: August 2010

In August 2010, I landed at Tel Aviv airport for the first time in 10 years. The airport had been renovated, but still, nothing was foreign to me.

On the contrary, Tel Aviv appeared familiar as never before. It was August and it was very hot. On the next day, I went to Ramat Chen, a suburb of Tel Aviv with mostly private mansions.

Because of its great location – just next to a national park and highway 4 – Ramat Chen is a very popular place, and very expensive.

At Aluv David Street 185, there is a German retirement home. Erna Goldmann has been living there for years; she has a nice little apartment on the ground floor, with an amazing view of the garden – with trees, bushes and huge cacti. I called Ms. Goldmann several times; she was awaiting me and was looking forward to the interview.

If you saw her, you wouldn’t believe that she was 92 years old. And, judging from the way she spoke, she would still have passed for a German – except for the occasional Hebrew word, like “nachon?” [Hebr.: “right?”].

On the telephone, we had great conversations, and we laughed a lot. But there were a lot of things in her life that Ms. Goldmann was not able to or did not want to remember.

- My family

I’ve never got to know my maternal grandmother. Her name was Eva [Jew.: Chava] Rapp. When I was born, she had already died. My Jewish name is also Chava; I was named after my grandmother.

My maternal grandfather’s name was Michael Rapp. In Frankfurt, we lived together with him at Eschenheimer Anlage 30. Eschenheimer Anlage was a huge complex – there were houses to the right and to the left, and the street between them was called Eschenheimer Anlage.

On it’s beginning, there was the Eschenheimer Tower, landmark and oldest building in Frankfurt. The house we lived in belonged to my grandfather. It hat three floors. On the lowest floor, a doctor lived with his family; my grandfather occupied the middle floor and we lived on the second floor. There were also rooms for the service staff in the attic.

My grandfather was a tall, handsome man. Supposedly, he was very well known in Frankfurt. They told me that he had a coffee import company. Until inflation set in in 1923, he was very wealthy, but then he lost a lot of money. But when I think back, we still had a good life. We had a cook and housekeepers – and a seven-bedroom apartment.

The way I knew him, he didn’t do anything. He was sitting at home at his desk, where he read newspapers and wrote letters every morning. That is the only thing I remember.

My grandfather was religious. He only ate kosher 1 food and didn’t drive on Shabbat 2. He kept all holy days and went to the synagogue regularly. My father and my grandfather went to the synagogue together. But my grandfather also bought a Christmas tree for our non-Jewish staff, organized presents and lit candles.

I remember that, I saw it. I was a child, and something like that always looks beautiful and impressive. But otherwise we didn’t have anything to do with Christian holidays.

My grandfather’s life ended tragically. He didn’t manage to get out of Germany. My brother, my mother and I had already been gone. He had to give up his house and lived in a Jewish hotel. When the hotel was Aryanized and the owner deported, a Christian family hid him in Frankfurt.

I don’t know when he died, but I know he didn’t die in a concentration camp. But he was alone, without his family.

My grandparents had four children. My mother Rosa – people called her Rosi – and three sons. All the children were born in Frankfurt. Julius Jonas Rapp was born in 1869, Ernst Juda Wilhelm in 1880 and Daniel Michael in 1882. Daniel Michael was only two when he died.

My mother Rosa was born on April 28, 1885.

Ernst died in 1918, after the First World War, of Spanish Influenza. It was an epidemic. Obviously, I didn’t know Ernst. But I own a Tefillah [the word Tefillah actually means prayer, but in this case, it refers to a family register], which my grandfather gave my mother in 1937, when she left for Palestine.

There’s everything in there. I only knew my uncle Julius. He was a stock exchange speculator and very wealthy. He lived in Berlin, in a district named Wilmersdorf, at 83 Paulsborner Straße. He was married twice; his second wife’s name was Anna Benon. She had a son named Günter.

Uncle Julius fled from Berlin and made it to the south of France. But then they caught him. From the internment camp in Gurs 3 he was deported to the death camp Majdanek 4 and killed. His son Günter fled to South America. That’s what I know. After the war, he visited my brother Karl in Jerusalem, but I wasn’t there.

The apartment had seven rooms and a balcony. We had a dining room, a Gentlemen’s Room [original: Herrenzimmer] – Gentlemen’s Room sounds stupid today – a salon, a bedroom for my parents, two rooms for my brothers and one room for me. In front of the house, there was a small garden; a green space with a small fountain.

My grandfather’s house still exists. But it was remodeled after the war. I don’t know exactly, when I was in Frankfurt the last time; I think it was about 20 years ago. I was invited by the city of Frankfurt, and I also visited the house.

It is higher now, one floor was attached, but otherwise it pretty much looked the way I remembered it. But I did not go in; I don’t know anyone in there anymore, what should I have said? Stupid, right?

My father’s parents came from Worms [Germany]. Their name was Guggenheim. I have never got to know them, even though they had become fairly old. I don’t know, why I didn’t know them, why they never came to visit us. My parents went to visit them; that I know.

They didn’t take me with them on the trip, I was a small child, and from Frankfurt to Worms it was quite a long trip. My father Theodor had five sisters; he was the only son. There were my aunts Gina, Alice, Sofie, Klara and Emma.

Aunt Emma and aunt Klara lived in Berlin, aunt Gina with her daughter and stepson in Bad Homburg. They had a small factory there. Aunt Alice and aunt Sofie lived in Frankfurt.

When my aunts from Berlin and Bad Homburg came to visit us in Frankfurt, I remember, they stayed at the hotel “Frankfurter Hof”. I knew all my aunts, but I didn’t have a close relation with them; to me, they were just old people.

Aunt Gina survived the concentration camp in Bergen-Belsen 5 and died a few years later, after the end of the war, in Holland. Aunt Klara survived the war with her family in America. My other aunts were killed in the Holocaust.

I don’t know exactly, where my parents got to know each other, but I know that it was – as it was common at that time – an arranged marriage. There were no youth movements, where young people could have got to know each other. My parents got married in 1903 or 1904.

My father was a corn merchant. He took over the business from his father. He had two or three employees at the office. I remember that I visited him at the office when I was a child. There were no typewriters yet, only big books and inkbottles. They wrote in Sütterlin script back then. My god, that was such a long time ago!

- Growing up

My father left the house in the morning and came back for lunch at noon. The office was close to our house; one could easily walk there. After lunch, he went back to the office and returned around seven.

We kept a kosher household. There were few kosher butchers in Frankfurt, even though there were many Jews. But Frankfurt was not a big city back then, and it wasn’t as nice at it is today. We celebrated Shabbat each Friday. They cooked in the morning and warmed it up later.

Back home in Frankfurt we used to light candles at Chanukah 6 and at Yom Kippur 7, my father spent the whole day at the synagogue. My mother wasn’t there all day, but she also fasted until the evening. My brothers did not go to the synagogue at all. They were good Jews, but they were not religious.

I continued to celebrate Shabbat later with my family. We thought that this was a nice evening. We also celebrated Chanukah. We lit the candles and gave presents to the children. It doesn’t have anything to do with religion, though; we just thought it was homely.

We celebrated all the high holidays. My husband led the Passover Seder 8; he liked to do it and he did a good job, and we used to invite a lot of friends and children. We were around fifteen, sixteen people.

We spent a lot of time preparing for these evenings, and we really looked forward to them. I don’t know when I saw the Wailing Wall for the first time. I just remember that it made a huge impression on me.

My oldest brother Karl was twelve years older than me; he was born on January 12, 1906. My brother Paul was seven years older than me; he was born on April 18, 1910. I was born on December 22, 1917, in our house in Frankfurt. Back then, everybody was born at home, and not at the hospital.

“My dear granddaughter Erna Guggenheim was born during the night of December 21-22, 1917” – that is what my grandfather noted down in our Tefillah.

My mother was a tall, blonde, respectable woman. She was a loving mother. When I was young, she often kissed me, but when I entered puberty, a certain distance developed. I think that this is perfectly normal. My father was crazy about me: a little baby-daughter, after two sons.

That always makes parents happy, doesn’t it? I don’t know what kind of relation my brothers had with my father. My father wanted my oldest brother Karl to take over his business. But for Karl, this was out of the question – thank God! Karl was not born to be a tradesperson; he was an intellectual guy.

My mother often said – I still hear her – “Oh, how your brothers spoil you!” I had a great relationship with my brothers. They did spoil me. Karl studied medicine at different universities; in Frankfurt, Munich, Berlin, and every time he visited us in Frankfurt, he took me out to Café Laumer at 67 Bockenheimer Landstraße.

That was really something special. There were not a lot of cafés in Frankfurt at that time, and Café Laumer was a very famous one; it still exists today. I was a child back then, and I was always very proud when my brother took me there.

We had a Jewish maid and a Christian cook. And when we were small, we had a nanny, too. During the last few years, until 1929, there were only the cook and the maid. The Jewish girl lived in our house.

But not in our apartment; she lived up in the attic. She used to take me for a walk or went to the park with me. She was much older than me – I was still very young. I know that she was able to flee to the United States.

My parents did not go to the theater very often, but sometimes they went to see concerts and they often invited guests. We only had Jewish friends and acquaintances. My mother attended a Jewish girls’ boarding school, where she was taught home economy.

She had made many friends back then and still spent a lot of time with them. She talked to them on the phone in the morning, and then they went for a walk together.

Once I went to the palm garden with her early in the morning, and there was also a friend of hers with us. My father worked all day. At the most, he read the newspaper in the evening.

Until 1929, we had a good time. But after 1929 – when I was 12 years old – the economic crisis had completely changed our lives. Our store did not generate sufficient profit. First, we remodeled our apartment: from a 7-bedroom into a 3-bedroom apartment. Even today, after decades, I still admire my mother, how she could take all this. She was very realistic.

I went to a Jewish school together with my friends. There were two Jewish schools; I attended the Samson-Raphael-Hirsch School, which was named after a famous rabbi. The Hirsch-School was the more religious school of the two. It had been modern in our circle to send the kids to a Jewish school for the first four years, and then to a Christian school, so that they would learn as much as possible.

But in my days that was not the case anymore. We were already approaching the Nazi-era. So, I didn’t go to a different school after the first four years. I attended the Samson-Raphael-Hirsch School for 10 years.

Of course, I had religion classes at school, but I was not very interested in them. I liked languages, but I was not a good student. I didn’t study. Even though my brother taught Hebrew classes in Frankfurt, when he was back home, I didn’t learn Hebrew.

I returned home from school at 1pm. Then our maid served lunch, and we all ate together. After lunch, my mother used to take a nap, or would sit next to me and help me with my homework.

Then I went down to the street to play with my friends; sometimes we played hopscotch [Hickelkreis]. We would draw different forms onto the street and hop on one leg from one box to the next. I would also ride my bicycle a lot.

My parents gave me a very pretty bike; it was my Rolls Royce. I can’t remember how old I was when I got it. Everyone had a bike at that time. I didn’t cycle to school though; I went by foot. It took me 20min to get there. In the afternoon, I would drive around with my girlfriends.

We used to dress differently back then. I was dressed very well, with coat and hat.

I also took dance lessons. For my first ball, I got a wonderful ball gown, made from light blue taffeta. It was tailor-made for me. There are beautiful photos; my brother took them. I sit in the Gentlemen’s Room, wearing the ball gown.

My brothers – and me too – attended a Zionist 10 youth movement named “Blau-Weiß” [Blue-White]. This youth movement was just one of many Zionist groups back then; it was very well known at the time. We didn’t go out to cafés, or to eat, we didn’t do that.

We went hiking, we sang, and we talked a lot about Israel. My life was never boring, because we were always together. We went to the Frankfurt City-Forest with our bikes and we went to camp together. I still have some photos from back then. We met several times a week, even after Hitler had risen to power.

In 1933 we went to a camp in Döringheim, which is located on the right bank of the Main, very close to Frankfurt. We slept in tents or in youth hostels and cooked over open fire. We went swimming and hiking. For our summer camp, we went to Switzerland. I loved these camps.

I can’t remember how long we were out together, but I don’t think it was longer than a week at a time. One of my friends from back then I met again in Israel, where she lived in a Kibbutz 9. I talked to her several times. Dear God, it’s been such a long time.

My brother Paul was a handsome man. He used to smoke his pipe, which was very modern back then. He went to Holland. He was done with school after ten years, but I don’t know what he did afterwards. We had an uncle in Holland, it was my grandfather’s cousin.

His name was Karl Rapp. He owned a paint factory in Delft. It made a lot of profits, and Paul went there after Hitler had risen to power, in order to get commercial practice.

We often went to Holland together: my parents, my grandfather and me. Sometimes I went alone with my grandfather. We went to Delft to visit my brother, to Den Haag and to Katwijk at the North Sea. We went on vacation there, visited my brother and my grandfather’s relatives.

We always used to stay for a while; I think it was two to three weeks at a time, 10 days at the least. In 1933, I still had school vacations. So I went to Holland again with my grandfather and my aunt Flora (one of my grandfather’s nieces, who kept his household).

In 1934, we lived with my brother; we had a room in his apartment. Paul had a primitive apartment in Delft; I think everything was primitive at that time.

Paul had a girlfriend in Holland; her name was Regina Fränkel. She was born in Frankfurt, too. She was my friend back in Frankfurt, and our parents were friends, too.

After Paul had finished his commercial education, the Fränkel family hired him for their button trade “Butonia” – they produced and traded in buttons.

The Fränkel family left Frankfurt early. People believed that Holland was safe. But when the Germans came to Holland, it got dangerous. It was a terrible time.

The Fränkel family emigrated to England, and my brother and Regina managed to get visas for Cuba. My brother knew somebody in Switzerland, who organized these visas in 1940, when Holland was already occupied by the Germans. Otherwise they wouldn’t have been able to get out of Holland.

When they were on the run, Regina got to know another man, whom she followed to the United States. My brother went to Cuba alone. It was a difficult time for my brother, because Cuba was primitive, and life was hard. But my brother was young, and he was happy to be safe.

At that time, one would take almost anything, just to get out. He wasn’t able to maintain contact with his family at the time, it was hardly possible.

From Cuba, Paul went on to the United States. There he signed up for the Dutch military, and that’s how he got Dutch Citizenship. So after the war, he went back to Holland.

He lived there and went back to working with the Fränkel family, this time together with their son. Later he even took over the button trade, and he was well off.

Paul was married twice. He had three children with his second wife Jetti:

Gidon, Michael and Margalit. His wife was very pretty – her mother was Dutch and her father from Indonesia. My husband and I often visited them in Holland; we were in Amsterdam for the first time in 1958. That was also the first time we left Israel. My brother died on February 9, 1974. His wife and kids still live in Holland.

Karl Rapp, my grandfather’s cousin, was killed during the Holocaust.

My brother Karl was a fervent Zionist. In 1933, he had finished his studies and he had even completed an internship at the Virchow-Hospital in Berlin. He was a general practitioner, but later, he only did scientific research.

After his internship, Karl left Germany and went to Palestine. My parents were ok with it; they were very modern. It wasn’t easy back then, you needed a certificate from the British, because Palestine was ruled by Great Britain.

Karl had realized early what happened in Germany and wrote to my parents over and over again: “You have to come, you have to come!” When he got to Palestine, he went to Jerusalem.

He had a girlfriend from Frankfurt; they met at the Zionist Youth Movement and they got married in Palestine. Her name was Irene; first she was in a Kibbutz, and then they got married and lived in Jerusalem. Karl stayed in Jerusalem.

He worked at the University, got his PhD in nutritional sciences and became a professor. Karl did nothing but read and work. My brother taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and published 250 scientific works and books.

When he visited me in Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan or Ramat Chen, he always came in with a book under his arm: “Shalom, how are you?” And then he sat down in a chair and read. But when he got older, he changed, because his vision got blurry and he couldn’t read anymore.

Then he started to get interested in conversations. Karl had three children, two sons – David and Amnon – and a daughter, Ruth. Ruth died in a car accident 20 years ago. She was on a trip through the United States with her husband when it happened. Karl died on October 15, 2002, in Jerusalem.

I met my husband in 1933 in the Zionist Youth Movement “Blau-Weiß”. His name was Martin (Jewish: Moshe) Goldmann. He was 20, and I was only 16. Moshe lived in Dessau. I think his mother came from Vienna; his father Adolf Goldmann was born into an eastern European Jewish family from Poland.

He had no formal education. Every letter he sent was written by my mother-in-law. She was the only one who wrote. She tended to everything that had to be written. She was religious, but traditional. They celebrated the holidays and kept kosher.

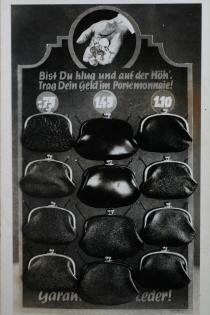

My father-in-law emigrated to Germany from a Polish small town when he was 19 years old. He didn’t have anything. But over the years, he established a big leatherwork factory, got a house and a car with a chauffeur. Before the war, he even presented his products at the Leipzig Trade Show. “If you’re smart and on the top, buy a purse in our shop” – that was one of his slogans for his products. Lotte, his oldest daughter, also worked in the factory.

My grandfather, too, was a glowing Zionist. He went to the 17th Zionist Congress in Basel with Moshe and Moshe’s sister Lotte. They got there, and my father-in-law was asked: “Mr. Goldmann, do you have an invitation?” Of course he didn’t have an invitation.

So he said: “My name is Goldmann, I want to get in there with my two kids.” They told him that he couldn’t come in without an invitation. So my father-in-law took the work clothes and brooms from the cleaning staff, everyone put on the clothes and took a broom, and that’s how they got in, and they even got good seats.

So Moshe was a child of good, Jewish family – but an Eastern European one. And my father was a very Western European Jew. That was a huge difference back then. The Western Jews disliked the Eastern Jews. They were not classy enough, even though many Eastern families had come a long way and had often achieved more than us. But Eastern Jews remained Eastern Jews.

My father-in-law’s brother owned a fur store in Dessau. With his wife Jenny and his children Arnold, Marianne and Bernhard, he managed to escape to Australia in 1939.

There was a quarter in Frankfurt – Ostende (East-End) – the eastern part of Frankfurt. Many poor Jews lived there. Those who were better off, the assimilated Jews, lived more towards the west. There’s one thing I’m thinking about at the moment.

The Yekke [Jews from Germany] lived secluded from the non-Yekke, i.e. the Jews who came from the east. I had a girlfriend at school, her name was Sonja. That’s all I remember about her. We were friends, and once I was invited to her birthday party.

And my mother said: “Should I let my child go there?” I’m telling you this, because it was typical of that time. Sonja’s family was from Eastern Europe. That’s the way it was back then.

Moshe was born in Germany. He completed a tanner’s apprenticeship close to Frankfurt, because his father wanted him to help with his factory as well. But in the end, it was completely useless, because he couldn’t do anything with it here in Israel.

Moshe went to Palestine in 1934. He visited me frequently between 1933 and 1934. But the most time we spent at “Blau-Weiß” together. After the meetings, he used to walk me home, and then we would stand on the street in front of our house for a long time, until my mum yelled from the window:

“Erna, come in now.” I don’t know if she was OK with me having a boyfriend, but it was never discussed. Moshe also visited me at home a few times. When he was not in Frankfurt, he would write me.

On a postcard, from Dessau, he wrote:

“Dear Erna, I can not thank you for your letter, because there was none.

Above all, I want to wish you a fine Seder. Ask ‘ma nichtane…’ [ma nischtanen haLeila hase is a Passover prayer from the Haggadah 11, which is recited by the youngest member oft he family. It means:

“How does this night differ from all other nights”?] and don’t eat too many Matzo 12 balls. Yesterday I returned from Berlin. I talked to almost all of my friends, Schattner, Sereni, Liebenstein, Schollnik, Georg, etc. etc. Sereni went to Rome for Seder 8 yesterday.

From there, he went to Eretz 13. Stay in country for three weeks, and then come back. In the evening, I went to the theater, “One hundred days” by Mussolini. Fouché, Gustav Gründgens; Napoleon, Werner Krauss.

It is the depiction of the 100-day-reign of Napoleon, after his exile. It was fabulous. The actors Gründgens, Krauss were amazing. After I hadn’t been to the theater for such a long time, this performance was a real pleasure. In the true sense of the word. So, let me know how you are. I will be in Dessau until Monday. My regards, I kiss you. Moshe. Dessau 29.3.34.”

Moshe also sent me a postcard with a swastika from Dessau. It says: “National Holiday 1934.” It was May 1, 1934. On the post stamp it says: “Fight unemployment, buy German goods.”

Moshe had three sisters. Jenny, Lotte and Malli.

Jenny came to Palestine in 1939. She lived in Berlin with her husband Josef Wahl. Her son Hanania was born there in 1939. Josef worked for the Jewish Agency 16. He had to leave overnight, because they were looking for him.

The Nazis were going to pick him up. So he disappeared overnight, went to Dessau and stayed with his parents-in-law. And from there, he quickly went to Palestine. Jenny remained in Berlin alone with her baby.

Luckily, she eventually made it, too. I remember how she got here with her baby Hanania on her arm. My husband and I went to Haifa by bus to pick her up. Hanania is 71 years old now. We have been in contact all the time. He doesn’t live far from here.

Malli was my husband’s younger sister, she was my age. She married Robert Sommer in Palestine. They had a daughter, Ilana. She has been working in a dental clinic.

Lotte was the oldest one and she had already come to Palestine in 1936 with the Youth Aliyah 14. She was married to Ludwig Ickelheimer, but they didn’t have children. Ludwig was from Dessau, too; he was a very popular cantor.

In Israel, he was called Jehuda, and he worked for Keren Hayesod. Their son Ruben was born at the same time as my oldest son Daniel: in 1940, 70 years ago. Ruben became a Physical Education teacher; unfortunately, he died a few years ago of cancer.

Tomorrow his wife will visit me. I spent a lot of time with Lotte, we were like sisters. We talked to each other for hours on the phone. First thing in the morning, we talked. I think about this often, because it is so great to be so close with one’s family-in-law.

We did everything together. She lived very close to us, on Ben Yehuda Street, corner Ben Gurion –Ben Gurion was Keren Kayemet back then. We did so much together. We went on excursions or picnicked together. We even had a car. I didn’t drive, but my husband did.

He couldn’t be without a car for one day. It was a big investment back then, a car. They didn’t have many cars. You could park anywhere. Anywhere! And children played on the street. When we moved to Ramat Chen, the street wasn’t even cobbled. The children played on the street, and then they came back up with dirty shoes.

Frankfurt was my home. But during the last year before I went to Palestine, there already were Nazi parades. We pulled down the shutters, because we were afraid. What life is that?

I learned how to make jewelry. It was not a profession that would be of much use in Palestine. But I had a talent, and my mum encouraged that.

My mother knew someone who was a bit of an artist, and he introduced us to Kurt Jobst. I got an apprenticeship at Jobst’s precious metal forge, where I stayed for almost a year. Mr. Jobst was a real artist, I learned a lot from him. He was not a Jew, but he only had Jewish apprentices.

We were three Jewish girls there. We had a close relationship with the Jobst family. In 1934, we even had a garden party at their house. In 1935, we made an enamel piece for the county Hessen-Nassau, I think it was for the city of Frankfurt. Kurt Jobst and his wife were wonderful human beings. He didn’t want to live in Nazi-Germany and left.

Then I started at the Städel School [School of Applied Arts], which was located in Mainzer Landstraße I think. One day, it was an afternoon in 1935, we wondered, why our boss wouldn’t give us any more work to do. Before we went home, they told us we couldn’t come back the next day, because they were not allowed to have any Jews enrolled at the school.

My father thought, Hitler would just go by. Just like a lot of the German Jews thought, Hitler would just go by. Oh, it’s horrible just to think about that! My grandfather and my father felt like German citizens: “Nothing can happen to us!”

That was their attitude. My grandfather, for instance, used to go swimming in the Main River. There was a designated public swimming area, and one day a sign was put up: “Entry is forbidden for Jews.” So my mother said to my grandfather: “Dad, you can’t go there anymore.

Didn’t you see what the sign said? Entry is forbidden for Jews.” “Well, but they don’t mean me,” my grandfather said. He couldn’t believe that this would apply to him as well. I remember this conversation as if it were yesterday.

I loved my father so much. He died in 1935 because he suffered from a heart condition. They didn’t do anything back then. Today, the treatment is completely different than it was 60 years ago. I remember that I was sitting at the table, couldn’t eat anything and cried. And a couple days later, I said: “At least my father died at home.”

My mother, my grandfather and I were at home alone, my father had died and my brothers had gone. We had a janitor, who lived in the room in the attic. What I’ll tell you now was typical of the time back then. The janitor had a daughter, she was my age.

Of course, she went to a Christian school, but because we were children, we used to play together on the street. One day, I think it was in 1935, we met on the street. She looked at me, but didn’t greet. That’s the way it was. It was the Nazi Youth education, and their parents were Nazis, too. It hurt a lot. It’s strange, I think about it a lot.

My mother then decided we had to go, too. It was probably also because my brother always wrote: “You have to come as quickly as possible!” Thank God he had already been in Palestine, and thank God he wrote that.

Because I was a member of “Blau-Weiß” – where we talked a lot about Palestine, Kibbutzim and other things in Palestine – it was self-evident for me that we would emigrate to Palestine. It wasn’t only self-evident, it was our goal.

My brother got a certificate for my mother, and I got one, because I was supposed to attend the Jerusalem Academy of Applied Arts, the Bezalel School. It was clear to us that we would leave Germany forever. Most of my mother’s friends had already left.

Only a few stayed behind. It was a time of dissolution. We didn’t know what was going to happen in Germany. We experienced this strong sense of anti-Semitism, but what eventually happened, we had not anticipated.

Of course, no one could have anticipated something like that, even though there were Hitler-speeches, in which he really stirred up hatred against Jews. In Frankfurt, there were Nazi flags everywhere. I still shudder today when I think about it!

Before I went to Palestine for good, I went for a three-month-visit in summer 1936. I wanted to visit my boyfriend Moshe, and I thought, maybe I could stay there for good. But after three months, the British didn’t extend my visitor visa. So I had to go back again.

My brother picked me up at the harbor in Haifa. It took a whole day on the train to get from Haifa to Jerusalem back then. There were Arabs sitting in our compartment with us. They offered me figs and other fruits.

I didn’t want to take them, but my brother said I had to, he said I mustn’t reject them. I hadn’t known any Arabs before, they were so foreign to me because of what they were wearing, but they were very, very friendly.

I can’t remember what kind of impression I had of the landscape. I knew that I was in a completely different part of the world. Nothing was similar to what I was used to, but I was prepared for that. I wasn’t interested in the vegetation, I was interested in city life.

I had my brother, I had my boyfriend, nothing bothered me. I was young, I didn’t have any problems. I lived with my brother in Jerusalem. It didn’t look anything like the Jerusalem of today. Everything was primitive.

But I wasn’t shocked. I was with my brother and my future husband, and I was twenty years old, so there were no problems. If you’re older, maybe 40 or 50, adaptation may be much more difficult.

But when you’re 20? My brother had a 2-bedroom-apartment. Later, my mum lived in this apartment, too, and I stayed there until I got married. Also, my sister-in-law, Irene, who was pregnant with her first child, lived there; and there was a time when here father moved in, too. All of us lived there, in those two rooms, and it worked. It wasn’t even awful.

My sister-in-law had a small wardrobe in the hallway. I put three dresses in there, the other ones I left in my suitcase. That’s the way it was, but it didn’t bother me and it didn’t make me unhappy.

Moshe didn’t have an apartment then. He lived with a friend in the countryside and worked on his the farm. It was a Moshav 15 in Pardess Hanna, close to Hadera. I liked Palestine a lot, but I had to go back to Frankfurt.

Then my mother and I started to pack our things. We dissolved our household; at that time you could even take big boxes to Palestine. I still own a lot of things that we took from our house in Frankfurt. We didn’t take any furniture, but smaller things. We also wanted to bring carpets, but my brother wrote: “Don’t bring carpets, you won’t need them here.” Everything was so primitive in Palestine back then; we only got carpets much later. But still, I’ve regretted that we didn’t bring them.

- Immigrating to Palestine

My mother got her certificate first, mine came a bit later. Because the certificate had to be used before a certain date – otherwise it would have expired – my mum had to leave without me. I stayed in our house, in a room in the attic. We had already abandoned our apartment.

I was alone for two, three weeks. I can’t remember how I felt, and I can’t remember what I did. Finally, there was a note from the Jewish Agency in the mail that I could pick up my certificate. The only thing I had with me was a suitcase with a few dresses.

First, I went to Switzerland by train. I had two cousins in Basel; the girl was a bit older than me and she was already married. Both emigrated to the United States later. I lived with them for a few days, then I went to Italy, and in Italy I boarded the ship.

This time around, the ship that went to Haifa was cramped with people. I don’t like being on a ship, it is wobbly and I get seasick. I think I was in a cabin together with two or three girls.

When I arrived, my brother picked me up again. My mum stayed in Jerusalem. Moshe didn’t come to Haifa either, but we met the next day. I went to see him, and I got there with a sherut, a share taxi. Moshe rented an apartment from a Yekke family. And when I got there, they had a bed prepared for him in the living room, so that we wouldn’t sleep together.

I left Frankfurt for good during the summer of 1937 and I got married in the garden of a small hotel on Yarkon Street in Tel Aviv, on December 25, 1937. This hotel doesn’t exist anymore. It was an intimate wedding:

my mother, my brother Karl, his wife Irene, her father, an aunt and my father-in-law, my mother-in-law’s sister, Lotte (my husband’s sister) and her husband Jehuda Ickelheimer (we called him Ickel), and some friends we knew from the youth movement, who had emigrated to Palestine, too.

My father-in-law came from Dessau to Tel Aviv for the wedding, and after that, my husband and Ickel said: “You are not going back!” But he left nonetheless. But he didn’t go back to Germany, he went to Czechoslovakia.

From there, he called his wife and told her to drop everything and join him immediately. My mother-in-law took whatever she could grab and left. They never went back to Germany.

What I’ve always appreciated a lot is that we all got here together, and no one stayed in Germany. You know, the family staying together. You don’t find that very often. And thank God, I left early. But the whole thing is still close to me, as if it were yesterday. The older I become, the more it gets to me.

My father-in-law didn’t have enough energy to build something new. But he managed – with the help of Jewish organizations – to transfer some money out of Germany. He bought a big house in Petach Tikva, together with an Egyptian Jew, and my father-in-law administered the apartments.

My parents-in-law were not doing very well, until they got a restitution payment from Germany during the 1950s/60s. It was good for them, because they needed the money. Considering the fact that his factory in Germany was really big, it wasn’t a lot of money, but at least it was something.

So things got better for them. In 1964, they celebrated their diamond wedding – that’s 60 years. It was a big party. My father-in-law died in 1965 in Tel Aviv, when he was 85 years old.

You could find everything you needed in Tel Aviv in 1937: streets, movie theaters, cafés. We sat together with friends, talked and drank coffee. My sister-in-law lived on Ben Yehuda Street, and we lived on the corner of Keren Kayemet/Emile Zola. Keren Kayemet is Ben Gurion Street today.

We had a beautiful apartment. In the morning, we went down Ben Yehuda Street, and we had to stop every five minutes: “Oh, hello, when did you get here, how long have you been here?” I was feeling great. I could go to the beach in shorts and meet friends. The whole Ben Yehuda Street spoke German!

But when I think about it today: everything was so primitive! When I got married, we didn’t have an electric fridge. We had this kind of refrigerator, where you had to put in ice. And we didn’t have any gas for cooking; we had to cook on a Primus stove. But it seemed natural to me. I adapted, and I knew that this is how it was and that there wouldn’t be anything else.

My husband had a small transport company. We didn’t have a lot of money, but somehow it worked. Then World War II broke out, and he joined the British military. But he didn’t have to go to Europe, he stayed around here as a chauffeur.

My son Daniel was born on June 2, 1940. Just after the war broke out. Even Tel Aviv was bombed sometimes. We lived on the third floor, and I didn’t want to go down each time the alarm went off. Then we moved to Petach Tikva, where my parents-in-law owned this big apartment building. It was terribly primitive, too, but what was I supposed to do?

Many people had big problems. But somehow, we all mastered our lives. It was very difficult for my mother. My brother sent her money regularly from Holland and I think that’s what she lived on.

I sometimes have to smile a little when I think of it: my mum was a housewife, just as much as I was a tightrope walker. She had no clue, because she hadn’t touched anything in our Frankfurt household. Then, in Ramat Gan, there was a man whose wife had died, and he stayed alone.

He was wealthy, and he wanted to hire a maid, because he wanted to have somebody at home. Our relatives who lived here managed to get the job for my mother. My mum and this man then became friends, but when my mum was diagnosed with cancer, she moved out.

But she was there for a few years. Then she moved back to Jerusalem and rented a room in a family’s apartment in Rachavia, a Yekke district – almost everyone spoke German. She was a cheerful soul, but when I think back, I see now how it was really difficult for her. She died in 1948 in Jerusalem.

- After the War

When Ben Gurion declared Israel’s independence in May 1948, war started immediately afterwards. My husband took our son Dani – he was eight years old, and Rafi wasn’t even born – and took him from Petach Tikva to Tel Aviv.

There was a big fuss, and there was an assembly on the main square and in front of the municipality. It was very exciting for me, for all of us. We had waited so long for the English to leave and for us to become independent. Until then, Israel was under British mandate.

From this day onwards, it was Israel; it was our country. And from now on, Jews could legally immigrate.

And then, immediately, war broke out. In this war, too, my husband was a chauffeur for an officer. He drove his own car, though, because the state of Israel didn’t have any money to get official cars. Much later, my sons went to the military as well. There were many wars, but they never really had to go to war, it was only military service.

Then we lived in Petach Tikva for about ten years. I made my own jewelry, which I sold at a WIZO store in Tel Aviv. I had a table and a small machine – just what you need to make jewelry. Back then, for the first ten years, my mother-in-law often looked after Dani.

Then we moved to Ramat Gan, and in 1951 my son Rafael was born. Rafi was completely different than Dani. Dani was blonde at first, then he got darker. Rafi is a very light type. Both children were lovely.

But the age difference – eleven years – was quite big. We lived for about ten years in Ramat Gan. In 1963, we moved to Ramat Chen, where we built a house. I lived in this house for forty years. We had a huge garden.

When we moved there, I stopped making jewelry. When you have a big house and a huge garden, you want to invite all your friends, and you don’t have any time to spare.

My husband established a profitable business. He started out with rubber. There was a Kibbutz, haOgen, where they produced plastic foil. It was the beginning of plastic. My husband bought this foil and then re-sold it, so that curtains, tablecloths, etc. could be made.

That was very profitable! Then we also imported from Germany. My husband was one of the first people to do something like that. Then he even established a factory, where plastic was produced. My son Daniel wanted to work at this factory after school.

My husband wanted that, too. And Dani did, but he wasn’t very successful. It was a small company, which my husband founded with somebody else. They produced and sold plastic. And Dani was very technically talented, he should have studied engineering or something like that. But he didn’t want to study, he wanted to work in my husband’s factory.

In 1964, Dani got married. At that time, we already lived in Ramat Chen. His wife Pnina was a teacher. Her father was born in Israel; I think her family has lived here for generations. Pninas mother was born in Egypt though. I liked her family a lot.

My husband was a very active man. He loved cultural events, especially concerts, because he was very musical. He died in 1967 of heart failure. I think about it much too often. He had a heart attack, and they brought him to the Tel Hashomer Hospital.

Then he was lying there and they didn’t do anything. Today, I still can’t believe how they couldn’t do anything. I’ve been alone for such a long time, forever. I was 49 years old back then, now I am 92 years old. I should stop thinking about it…

My son and his wife had two children. They named their son after my husband, Moshe. He is 43 years old today; and their daughter, Joni, is 40. Moshe was born on my husband’s first death-day, and Pnina’s parents decided that he should be named after my father.

I didn’t want to get involved; I thought it was her decision, but of course I liked the idea. Moshe and Joni have kids of their own now. All of them live in Israel, and I keep in contact with tem. My son Dani died in 1990 in a car accident between Eilat and Tel Aviv.

Like Dani, Rafi started to work in my husband’s factory immediately after he had finished school. We still own the store today, but it is not as profitable anymore. A lot has changed. There is so much competition, everything is produced in China, everything is so cheap. Rafi is 59 years old.

He lives together with his wife Hannah. She teaches Jewish History and her parents emigrated from Russia, when all the Zionists came to Palestine. His daughter Odet and her son Adam live close to me.

I’ve been living in this retirement home in Ramat Chen since 2003. It was the year of the second Iraqi war. I didn’t want to stay at home alone at that point. So I got an apartment here. I thought that, when war breaks out, I want to be here, and not at home alone.

And then I saw this beautiful apartment and I stayed. It is a really nice retirement home, the house is beautiful. My son Rafi only lives a few minutes away, and he visits me regularly.

All our friends in Israel had come from Germany. We talked German at home, and I still speak German. I speak Hebrew, too, but it’s hard for me to read and write.

With my daughter-in-law and with my grandchildren, I speak Hebrew, but with my son Rafi, I always speak German. But only when we are alone. Otherwise the other people don’t understand what we’re talking about, and that’s not very polite.

I didn’t talk to my sons about my own history, and they were only interested in things they had read or heard somewhere. Personally, I didn’t really experience anything, you know, but there were people in our family who died during the Holocaust. But my parents and my siblings, and my husband’s as well, we all manage to stay together. Our closest relatives survived.

My sons went to Poland with their school classes, to visit Auschwitz. My grandson was there, too. For young people, its not the same as it was for us. Even though I did not directly experience something terrible, it feels as if the dread and murder is still with me.

We celebrated my 90th birthday in Yaffa. Rafi picked a very nice restaurant. On this evening, it was decorated beautifully, just for us. It was a wonderful celebration, and even two nephews and a niece from Holland – my brother Paul’s children – came for a surprise visit.

I am not a politician, but I think that the situation with the Palestinians is quite desperate. It’s been going on for so long. There are no solutions. But it is like Ben Gurion said: “Anyone who doesn't believe in miracles is not a realist.” But times are changing, and in Ben Gurions times, everything was different. The Palestinians were not as powerful back then.

I don’t know if they made mistakes at the beginning. Many people said that it was wrong to occupy all the Arab territories. But I am not very political, and the only thing I can say, is what I hear. And I don’t even know if this is my own opinion.

It is difficult to say, 20, 30, 40 years later, what would have been, if… But there is one miracle: this country has been through so much, so many wars, has been attacked countless times. And still, it is progressing. All along!

- Glossary:

1 kosher [Hebrew: pure, fit]: In accordance with the Jewish dietary laws.

2 Shabbat [Hebrew for "rest" or "cessation"]: the seventh day of the week, sanctified by God in reminiscence of His rest on the seventh day of the week of creation. On Shabbat, work of any kind is prohibited. Instead, the spiritual aspects of life shall be contemplated.

Shabbat starts on Friday evening and ends on Saturday evening.

3 Gurs: A French village on the edge of the Pyrenees, around 75 kilometers away from the Spanish border. During the German occupation of France, an internment camp was established in Gurs. The camp held up to 30 000 prisoners at once; among them were 'undesirable persons' and Jews.

In 1942 and 1943, 6000 Jews were deported from Gurs into the extermination camps.

4 Majdanek: The Majdanek concentration camp (on the outskirts of Lublin) was the first concentration camp established by the Concentration Camps Inspectorate [Inspektion der Konzentrationslager; the central SS administrative authority for concentration camps].

5 Bergen-Belsen: 1943-1945. Nazi concentration camp in Germany, in the Bergen and Belsen districts, near Hannover (Lower Saxony). At first designated for European Jews. Since 1944 transports of inmates unable to work were sent to Bergen-Belsen and they were murdered there.

In 1944 a labor camp in tents was created in Bergen-Belsen for Polish women. 75,000 inmates of different nationalities went through the camp, approx. 50,000 people died of sickness, starvation or exhaustion. The liberators found bodies and fatally ill people reduced to a skeleton.

Therefore, Bergen-Belsen became a "symbol for the most terrible atrocities and the inhumane barbarity of the National Socialist concentration camp system", particularly in Great Britain, whose troops liberated the camp.

6 Chanukka [Hanukkah, Chanukah]: Also known as the Festival of Lights. This 8-day celebration commemorates the re-dedication of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem that took place in 164 BC after the Maccabean uprising against Hellenized Jews and Syrians.

The Maccabees succeeded and re-stored temple worship. According to tradition, there was only enough oil for one day, but through a miracle, the lights remained on for eight days, until they could produce new, sacred oil.

7 Yom Kippur: "Day of Atonement"; one of the holiest days of the Jewish year, celebrating atonement and reconciliation. On this day, it is forbidden to eat, drink, bathe, wear leather or have sexual relations. Fasting - the total abstinence from food and drink - starts shortly before sun set and ends on the following day when the night closes in.

8 Seder [Hebrew "order" or "sequence"]: Short for the Passover Seder. This ritual marks the beginning of the Passover holiday. On the Seder evening, the story of the liberation of the Israelites from slavery is told in the family or the community.

9 Kibbutz [Pl.: Kibbutzim]: Collective, agricultural communities in Israel, traditionally based on principles of shared property and collaborative work.

10 Zionism: a primarily Jewish political movement that has supported the self-determination of the Jewish people in a sovereign Jewish national homeland. The movement was founded during the second half of the 19th century and the term “Zionsim” was coined in 1890 by the Viennese Jewish journalist Nathan Birnbaum.

The beginning of modern Zionism was marked by Theodor Herzl's work "The State of the Jews" (1897). Until the Holocaust, Zionism was a minority movement within the Jewish community.

11 Haggadah [Hebrew: "telling"]: The religious text that is read and sung together with the family during the Passover Seder. It tells of the period of slavery in Egypt and the exodus into freedom.

12 Matzah (hebr

מצה, matzá; Plural hebr. מצות, matzót): Unleavened bread made of white plain flour and water. Substitute for bread during the Jewish holiday of Passover.13 Eretz Israel [hebr.: ארץ ישראל]: a biblical term referring to the Jewish or Hebrew nation-state. The term was picked up again at the end of the 19th century with the beginning of political Zionism and is still widely used today in Israel.

14 Youth Aliyah: Organization founded in 1933 in Berlin by Recha Freier, whose original aim was to help Jewish children and youth to emigrate from Nazi Germany to Palestine. The immigrants were settled in the Ben Shemen kibbutz, where over a period of 2 years they were taught to work on the land and Hebrew.

In the period 1934-1945 the organization was run by Henrietta Szold, the founder of the USA women’s Zionist organization Hadassa. From that time, Aliyyat Noar was incorporated into the Jewish Agency. After World War II it took 20,000 orphans who had survived the Holocaust in Europe to Israel.

Nowadays Aliyyat Noar is an educational organization that runs 7 schools and cares for child immigrants from all over the world as well as young Israelis from families in distress. It has cared for a total of more than 300,000 children.

15 Moshav [מוֹשָׁב, plural מוֹשָׁבים moshavim, lit. settlement, village]: Israeli town or settlement; cooperative agricultural community of individual farms. Similar to a Kibbutz, but fams in a moshav have usually been individually owned.

16 The Jewish Agency was founded in 1929 as a representation Jewish interests during the time of the British mandate in Palestine. It acted as an official representation of the Jewish population.

After the foundation of the state of Israel, the chairman of the Jewish Agency, David Ben Gurion, became the first premier. Many tasks of the agency were taken over by the state, but, until today, the Jewish Agency has been in charge of the immigration to Israel.