Ida Goldshmidt

Riga

Latvia

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: August 2005

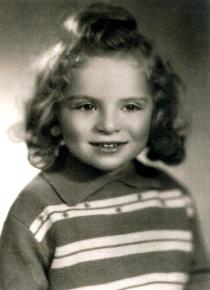

This interview with Ida Goldshmidt was conducted in the Riga Jewish Charity Center. There is a Jewish choir in this center, and Ida sings in this choir. We met after a rehearsal. Ida is one of those ladies, when each next year of their life only adds to their charm. She is a tall, slender, shapely lady with good stature. Her black hair with gray streaks is cut short. One can hardly see any wrinkles on her face. Ida wore light trousers and a light flowered blouse. This outfit was very becoming. It's hard to believe that this 74-year-old lady has lived a very hard life. Ida is very friendly and kind. She told me willingly about her family and her life, however hard these memories are for her.

My family background

Growing up

The war begins

Post-war

Married life

Our son Boris

Glossary

My parents' families lived in Daugavpils [200 km from Riga], Latvia. I have no information about my father's family. My paternal grandfather and grandmother died long before I was born. My father had brothers, but I never met them. They must have been scattered around the world. My father, Isaac Zaks, was born in 1886. I only know one thing about my father for sure, and that is that he studied at cheder. This was mandatory for all Jewish boys, and this is pretty much all I know about my father's childhood or boyhood.

My mother's family also lived in Daugavpils. I never met my grandfather. I don't know his first name, but his last name was Liberzon. I remember Grandmother well. Her name was Hana. My grandfather didn't live long, and my grandmother had to raise six children alone. My mama Buna was born in 1890. She was the oldest of all the children, and helped her mother to raise the other children. After Mama her brother Hersh, who was usually addressed with Grigoriy, the Russian name [common name] 1 or, I'd rather say, Grisha, an affectionate of Grigoriy, and Borukh-Zelek, or Boris in the Russian manner, were born. I know that Boris was the youngest of the children. Mama also had three sisters, but they lived in different towns with their families, and I never met them.

Before Latvia gained independence in 1918 it belonged to the Russian Empire [see Latvian Independence] 2. Daugavpils was within the [Jewish] Pale of Settlement 3, and Jews constituted a big part of its population. Only Jewish people with higher education, traders and craftsmen with specialties in demand in the town, were allowed to settle down in Riga. A major part of the Jewish population settled down in Riga after the [Russian] Revolution of 1917 4, when the Pale of Settlement was cancelled. I believe the Jewish population constituted at least half of the total population in Daugavpils. There were several synagogues in the town. Each guild had its own synagogue: butchers, leather tanners, tinsmiths, etc. All Jewish people were religious, and it couldn't have been otherwise. All Jewish boys had to go to cheder. All weddings followed the Jewish traditions. If a rabbi didn't bless the marriage, the man and woman were considered to be living in sin.

When World War I began in 1914, Nicholas II 5, the Russian Emperor, ordered to deport all Jewish people to Russia from Latvia. The emperor had concerns that Jews were to support the German armies, if they came to Latvia. My parents' families were also deported. I think my mother and father got married in Russia. However, they both came from Daugavpils and must have known each other before their deportation. All I know is that their first baby was born in Russia and died shortly after his birth. After the revolution, when the tsar was overthrown, my parents could return to Latvia. They settled down in Riga. Mama's brothers also lived in Riga. It was difficult to find a job in Daugavpils, and many people were moving to bigger towns looking for a better life.

Poor Jewish people mainly settled down in Moscowskiy forstadt 6, a suburb of Riga. Most streets were named after Russian writers and poets such as Turgenev 7, Pushkin 8, Gogol 9, etc. They had been named so during the Russian Empire, and their names were not changed afterward. There were also Moskovskaya, Kievskaya and Katolicheskaya [Catholic] streets. Even Katolicheskaya Street was mostly populated by poor Jewish people. My parents rented an apartment on the 2nd floor of a two-storeyed wooden house. It was owned by a Jewish man, and its tenants were also Jews. They were poor Jewish families, and couldn't afford to pay higher fees, and the owner wasn't much wealthier than the tenants. Other houses in this street were as shabby as ours.

My father became a cab driver. He bought a cart and a horse. The horse stayed in our yard. My parents' horses often died since my father had no money to feed them properly. This was like a vicious circle. A horse died, and my father had to borrow money to buy another horse. Then he had to pay back his debt, and again he had no money to feed the horse. He also had to feed the family. Mama didn't have a job. She had to take care of four children. Jewish women didn't work at the time. They had many children and had to take care of their homes.

My brother Todres, the oldest of the children, was born in 1921. The next was my sister Joha, born in 1926. My brother Haim-Shleime [Semyon] was born in 1929. I was born in 1931 and was the last child. I was given the name of Ida.

My maternal grandmother lived with us. Jewish mothers commonly stayed with older daughters. And there was another Jewish rule: brothers could only get married after all of their sisters were married. Mama's brothers also lived in Riga. Both were tinsmiths. Both brought Mama money every week in order for her to support Grandmother. Mothers were well-honored in Jewish families. I remember my grandmother well. She was short and wore her gray hair in a knot on the back of her head. My grandmother wore long, dark skirts and dark, long-sleeved blouses. My grandmother was kind and friendly. She always had a smile and a kind word for others. My grandmother loved her grandchildren dearly. She particularly spent much time with me. I was a sickly child. I was allergic, but I only know now that I was allergic. At my time the doctors couldn't identify the disease. Whatever food I ate I had red blisters on my skin. A doctor in the Jewish hospital [Bikkur Holim] 10 told Mama I would overgrow them, and this happened to be true.

Our family was a typical Jewish family. We lived a Jewish life. We lived in a Jewish environment, and the Jewish religion and Jewish traditions constituted a natural element of our life. We followed strictly all traditions, and it never occurred to anyone to skip any of them. Newly-born boys were circumcised. At the age of 13, boys had the bar mitzvah ritual. Of course, there were no big celebrations in our poor neighborhood, but there were mandatory rituals and treatments at the synagogue. I was just three, when my older brother Todres had his bar mitzvah, and don't remember any details, but I don't think there was a celebration. My parents couldn't afford it. However, I remember how proud he was, when he put on his tallit to go to the synagogue with our father. My husband also told me about his bar mitzvah, and it was about the same. There was a cheder in our neighborhood, and all boys attended it. My father also studied at cheder in Daugavpils in his time, and so did my brothers. Girls studied Hebrew and prayers when they studied at Jewish schools.

However poor we were, we celebrated all Jewish holidays in our family, following all rules. Mama saved money for holidays. When my father brought his salary, she put a few coins into a box. Mama cooked gefilte fish and chicken broth on holidays. We had that on Pesach, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. We also celebrated Sabbath. On Friday evening Mama lit candles and prayed over them. On the following day my father went to the synagogue. He never missed one Saturday. My brothers went to the synagogue with my father. Mama didn't attend all Saturday services at the synagogue, but she went there, and my older sister and I joined her. The synagogue was actually the only place of Jewish gatherings. Our poor neighbors couldn't afford to go to the theater or to a restaurant. The synagogue was the center, coordinating the Jewish life of our neighborhood.

There was a major clean up before Pesach. All belongings were taken outside to whitewash the walls and clean the windows. Mama and I cleaned the house from chametz. My father, holding a candle and a goose feather, swept off breadcrumbs that were purposely left in an open space. They were wrapped in a piece of cloth to be burnt. Mama baked matzah for Pesach in an oven. Mama added eggs to the dough, and it was yellow and crunchy like thin crunchy cookies. Now they make rectangular matzah, while Mama used to make it round. My sister and I assisted her. Mama made the dough and baked the matzah, my sister rolled the dough and I made little holes in it with a little wheel. We had to do everything very quick, because 18 minutes after the dough was made it was no longer good for matzah. Therefore there were smaller portions of dough made. There was plenty of matzah to be made to last through all days of the holiday. We had no bread at home throughout the holiday. Mama had special utensils for Pesach. During the year they were stored separately from our everyday utensils. Mama also used different utensils for meat and dairy products, though we hardly ever could afford meat.

On the first day of Pesach we got together for a festive dinner. For this dinner Mama made chicken broth, gefilte fish, matzah and potato puddings. In the evening we conducted the seder. Everything was according to the rules. There was special wine, and a big glass of wine for Elijah the Prophet. My father conducted the seder and read the Haggadah. He broke a piece of matzah into three and hid away one piece called the afikoman. One of the children was to find it and hide it away again to have Father pay the ransom. My brother Haim-Shleime was usually the one. There was also everything required for seder on the table: a piece of meat with a bone, a hard-boiled egg, greenery and a saucer with salty water. Our father told us what these stood for. The seder lasted long, but I didn't feel like sleeping. I kept staring at the glass meant for Elijah, and there seemed to be less wine in the glass, which meant to me that Elijah had visited our seder and blessed our home. After the Haggadah we sang Jewish songs. Jewish songs are usually sad, but we only sang merry songs at Pesach. My father couldn't afford to stay at home on all days of the holiday since we could hardly make ends meet. He only stayed away from work two days at the beginning and one day at the end of the holiday.

On Yom Kippur my parents, my older brother Todres and my sister fasted 24 hours. Haim-Shleime and I weren't allowed to fast, but we tried as hard as we could. On Yom Kippur everybody spent the day praying at the synagogue. We went to the synagogue with our parents. Children were allowed to play in the yard during the prayer. We also celebrated Rosh Hashanah and Chanukkah. Chanukkah was our favorite holiday. My mother's brothers visited us to greet grandmother and my parents. They gave us a few coins. We could buy lollies, which was a rare delicacy for us.

We only spoke Yiddish at home. This was the only language I knew, when a child. Later I learned Latvian. I don't remember how I managed to learn Latvian. We lived in the Jewish environment and went to a Jewish school. We even had the Yevreyskaya Street, Zidu Yela, in our neighborhood.

There were two Jewish schools in our neighborhood: 'Zidas skola' and 'Ebrais skola'. Zidas skola was a six-year general education Jewish school. All subjects were taught in Yiddish. We also had Hebrew and religious classes. Ebrais skola was a Hebrew school. All subjects were taught in Hebrew, and children studied the Torah and the Talmud. We went to Zidas skola. I liked studying, and my teachers praised me for my successes.

My older brother Todres tried to help our parents. Even when he was still at school, he tried to earn some money. My mother's brothers were tinsmiths. They rented a shop. Mama cooked lunch for them, and Todres delivered this food to the shop. Mama's brothers gave him some change for this, and he gave this money to Mama. After finishing school my brother went to work at the leather factory. He became an apprentice. When he started working, he brought home his wages, and life became easier, when two men were working. I was the youngest in the family, and my brother liked spoiling me. He gave me the most precious gift in my life. When he received his first wage, he bought me a purse. I can still remember it: red leather and a clasp with a shiny yellow lock. I believed it was made of gold. I had never had a beautiful thing like this before, and I put it on my pillow beside me, when I went to bed. When Todres started earning money, we moved to another apartment. It was also located in Moscow forstadt, but it was a better house and a better apartment. It was more spacious and comfortable. My grandmother moved in with us. In 1940 Todres went to learn the furrier's specialty. It didn't take him long to learn this vocation.

Mama's brother Girsh was single. Mama's younger brother Borukh-Zelek got married in 1928. His wife's name was Zhenia. She came from Riga. She also came from a traditional Jewish family. It goes without saying that they had a traditional Jewish wedding. They were very much in love, but they didn't have children for a long time. Their only daughter, whose name I can't remember, was born in 1935.

I have very dim memories about the establishment of the Soviet regime [see Annexation of Latvia to the USSR] 11. I was nine years old. I remember Soviet tanks decorated with flowers driving along the streets. Basically, our situation didn't change. The Soviet regime was loyal to poor people. Perhaps, our situation even improved. A pioneer unit [see All-Union pioneer organization] 12 was established in our school. Children joined the pioneer organization. My brother Haim-Shloime became a pioneer. I was too young, since the admissions started only in the 4th grade. My brother became a pioneer along with his other schoolmates. The children lined up and red neck-ties were tied round their necks. I wished I had been one of them. Actually, there were no changes in our life. Jewish schools were operating, though Jewish history and religious classes were cancelled. We studied the 'History of the USSR,' a new subject. We also observed Jewish traditions and celebrated Jewish holidays at home. The synagogue was open, and my parents attended it on Saturday. There were new Soviet holidays: 1st May and 7th November [October Revolution Day] 13. We didn't celebrate them at home, but there were celebrations and concerts at school. I sang in the school choir. We sang Jewish songs since we didn't study Russian at school.

In early June 1941 I finished the 2nd grade and my brother finished the 4th grade. We usually spent summer vacations at home. Our parents couldn't afford to arrange vacations elsewhere for us. We played with our neighbors' children and went to swim in the Daugava River. Wealthier Jewish families had summer houses at the seashore, but my brother and I had never seen the sea, though we lived just a few kilometers from the seashore. In June 1941 Soviet authorities established a pioneer camp for children in Ogre. Children from poor families could go there on summer vacation. My brother and I were also to spend the summer there. We were looking forward to going to the summer camp, and our parents were very happy that we would have decent vacations. I remember so well that when we were leaving, our parents gave us a whole bag of cheap candy. We had them in the bus and offered some to our friends. The trip started like a feast! Most children came from poor Jewish families. They were on the priority list of the camp.

There were small houses in the woods in the camp. There was a spot in the center where the children lined up in the mornings. The pioneer tutors reported to the camp director and then the flag was raised on the post. There was a flowerbed with flowers planted in the shape of a red star.

We were busy in the camp. There were clubs, and also, we went to the woods or to bathe. My brother and I were in different pioneer groups, and didn't see each other often. Sunday was the day of parents' visits. Our parents visited us once. They brought us sweets and candy. The following Sunday was to be 22nd June [the beginning of the Great Patriotic War] 14. We heard distant explosions in the morning. We ignored them. There were frequent military trainings, and we were used to such noises. Later we noticed that adults looked concerned about something. In the late afternoon German planes attacked the camp. The red star in the flower bed suffered the most. Perhaps, it was seen best from the planes. We were hiding in the forest during this air raid. At night evacuation of the camp began. We headed to the railway station where we boarded freight carriages. Children were crying asking to be taken home. We knew nothing about the war. We associated it with boys' games. Only the children who were ill at the time stayed in the camp for fear of epidemic, and they all died, of course.

Our train left Ogre. Children were crying, and our tutors tried to comfort us. My brother and I stayed together. Our train stopped at a crossing. There was another train with recruits right there. My brother and I were looking through the window, when all of a sudden we saw our older brother Todres. He was standing near the military train. Later we got to know that he volunteered to the front on the first day of the war. His gaze was sliding along our train, when he suddenly saw us. When he told us about it later, he said that his heart almost stopped. He didn't know whether we were alive or how our parents were doing. He ran to our carriage. He wanted to get in and talk to us, but he wasn't allowed to come inside. My brother and I also ran to the door, begging our tutors to let us see him, but all in vain. Our train started. My brother and I kept looking at Todres standing on the track. We saw the tears running down his cheeks.

Only after the war we found out what happened to our family. Uncle Boris told us the story, and he heard it from his Latvian acquaintances. When my parents got to know about the war, they prepared for evacuation. They packed their luggage onto the cart and were ready to leave, but Mama didn't want to go without us. She tried to get to Ogre, but there were no trains available, and she failed to reach us. The others were telling her that we would be taken care of, and she had to think about the rest of the family, Joha, Grandmother. Mama made up her mind to go, but they couldn't get to the opposite bank of the Daugava River. German planes were bombing the bridge, and our family had to go back. They stayed in Riga. A few days later German forces came to Riga. The Moscowskiy forstadt area was fenced with barbed wire to make a Jewish ghetto [see Riga ghetto] 15. At first Jews from Riga were taken to the ghetto, and then Jews from other towns followed. The first prisoners were those families, who lived in this neighborhood. In late November 1941 the shootings of prisoners began. November in Latvia is frosty, and there is usually snow on the ground. Prisoners were convoyed to Rumbula [forest] 16, about 15 kilometers from the ghetto, where they were killed. My father, mother, grandmother and my older sister Joha perished in Rumbula. My grandmother was perhaps unable to walk as far as the forest. It didn't matter. The Germans killed the weak ones who stopped to take a rest. There were no survivors. It didn't matter whether a person lived one or two extra hours on his last road. Maybe those who died on the way were luckier to avoid the horror of mass shooting. I think at times whether these Jews going to Rumbula knew what to expect or whether they were hoping to be taken to another ghetto? Of course, I will never get an answer to this question. In 1944 the Germans opened these huge graves in Rumbula to burn the remains of the people who had been buried there. They also crushed the bones in bone crushing machines.

In early June 1941 my uncle Boris' wife Zhenia and their daughter went on vacation to Pliavinias where Boris rented a room for them from Latvian landlords. Boris and his wife were hoping that their daughter would gain more strength during the vacation. When the war began, Boris was mobilized to the front. After the war we got to know that the Latvian landlords killed Boris' daughter even before the Germans came to the town. Zhenia hanged herself after this happened. Boris didn't know what had happened to them until after the war. Recently the memory of Zhenia and her daughter came back to me. My husband, my friend Ella Perl and I went to the exhibition 'Jews of the Riga ghetto.' We heard on the radio about it and didn't hesitate to visit it. My family members perished in this ghetto. I was hoping to find a mention of them at the exhibition. There was a large book of victims of the ghetto. However, I didn't find the names of my family, though Katolicheskaya Street where we lived was within the ghetto territory. Thus, I found the name of Zhenia Liberzon and her home address. The book also mentioned that she hanged herself after the vicious murder of her daughter. Zhenia was very young.

In June 1941 our train, full of children, was moving to Russia. The train was camouflaged with tree branches, so that German pilots wouldn't be able to identify the train. Regretfully, I cannot remember the places where we stopped. There were many stops. I knew no Russian, and couldn't remember Russian names. When the train stopped in a village or town, we got off, if there was an opportunity for us to stay for some time in school buildings or in local houses. For some time we stayed in a distant village where people had never seen a plane before. They used to look into the sky asking, 'What is that flying thing?' Usually a few children and a tutor were accommodated in a room. We were provided meals. However poor the food was, nobody starved. We never had enough food, and before going to sleep we often thought about our mothers' dinners. We didn't go to school. There were mostly children from poor Jewish families in our train. None of us knew Russian. We spoke Yiddish to one another and Latvian to our tutors. We couldn't attend Russian schools. Our tutors tried to teach us things, but they were not teachers. When the front line advanced we moved farther into the rear. We had left our homes with summer clothes on, and on our way we were given warmer clothes. Local women at places where we stopped felt sorry for us and shared their warm clothes with us. Of course, these clothes were different sizes. Now I know that we looked like scarecrows, but we didn't care then. So we kept moving till early 1943. We were called a children's home from Riga, but there were also children from other Latvian towns in our group. I don't remember if there were any Latvian children among us.

During this journey across Russia we faced anti-Semitism for the first time. We found out we were different from others. Speaking no Russian we didn't play with local children. We usually stayed in smaller groups. Local children used to follow a group of us shouting, 'Zhid, running along the line' [in Russian, the lines rhyme]. We knew the word 'zhid,' of course. Zhid in Latvia meant 'Jew' and had no abusive underlying note. This was the only word we knew, and we didn't know what the locals were shouting. Later we asked our tutors and they told us what it meant. The translation sounded nothing but funny, but the intonation and conduct of these boys indicated abuse.

In 1943 our former pioneer camp and current children's home arrived at Ivanovo [300 km from Moscow]. There was an international children's home, known all over the Soviet Union, located there. It was established in 1936 or 1937, during the war in Spain [see Spanish Civil War] 17, when Spanish orphan children started arriving in the Soviet Union. Initially, these children were let for adoption, and those coming afterward were taken to the children's home. Then came Polish children, whose parents were killed, when Hitler attacked Poland in 1939 [see Invasion of Poland] 18. There were children from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and when the Great Patriotic War began, Soviet children were also brought to the children's home. Also, there were many children from the countries annexed to the USSR in the late 1930s, early 1940s: the Baltic Republics, Western Ukraine and Moldova. They didn't know Russian, but there were also Russian children at the home.

My brother and I stayed together during our wanderings across Russia. In Ivanovo we were separated: my brother, being two years older than me, was assigned to a different group of children. In Ivanovo we attended Russian classes. Children learn fast, but what is surprising is that I forgot Yiddish, when I started speaking Russian. I remembered Latvian, though, and when I returned to Latvia, I could speak Russian and Latvian. I also spoke Russian to my friends from the Riga children's home. All children of different nationalities spoke Russian to one another in this international children's home. We faced no anti-Semitism in the children's home. There were so many different children at this home, that nobody looked foreign. Of course, life in the children's home was no idyll, and I would never believe those who say they were happy there. However good a children's home can be, it will never replace a family. However, we knew we had no alternative, and that we would have died, if it hadn't been for the children's home. Actually, we had sufficient food and clothes, studied, had clean beds and were treated all right. I was continuously ill in Ivanovo. The doctors really saved my life at the children's home.

I became a pioneer at the children's home, and I was very proud of it. I studied from the 3rd to the 5th grade at school at the children's home. I was doing all right at school. I had friends: three sisters from Latvia, their last name was Pesakhovich. They came from the eastern part of Latvia. Feiga, the middle daughter, was in my group and my class. Her older sister Fania and the younger Sonia were also my friends. My other friend was Sonia, a Polish Jewish girl, whose parents were killed by the Germans in 1939.

We knew the war was coming to an end. In 1944 Soviet forces advanced as far as Latvia. We looked forward to the day when Latvia would be free and we could go home. My brother and I often discussed how we would come home and our parents would be waiting for us. It never occurred to us that none of them had survived. We thought that they were in evacuation, but couldn't find us, considering that we were moving from one place to another.

In 1945 children from Latvia left Ivanovo for the Daugavpils children's home. In fall I went to the 6th grade. The majority of our tutors were Russian. They only spoke Russian. They treated us well, and there was no anti-Semitism in our boarding school. Our tutor, Tatiana, was a Russian Jew. I owe my life to her. In winter I fell ill with pneumonia. The doctor of the boarding school had no positive feelings about curing me. Our tutor's sister was a doctor in the municipal hospital of Daugavpils. One night I was taken to her hospital on sleighs. A bag with my dress, underwear and some food was beside me, but the cabman stole this bag. I was unconscious in the hospital for a long time. My tutor's sister brought me back to life. She felt sorry for the Jewish orphan girl and spent much time with me. When I recovered from pneumonia, I fell ill with measles. I don't know how I survived.

Two months later I returned to the boarding school. My head was shaved, and I rather looked like a skeleton. Our tutor helped me a lot. I had missed many classes. Tatiana helped me to catch up with the other children. We had individual classes, and I managed to complete the curricula of the 5th and 6th grade. In fall 1946 I went to the 7th grade. After finishing the 7th grade well, I was awarded a trip to Moscow. Ten children and a tutor went on this trip. This was the first time we went to Moscow, and everything was interesting. Moscow was being reconstructed, but theaters and museums were open. We went on excursions and to the theater. This was the first time I went to the theater, and I loved it.

Our boarding school tutors took efforts to find our relatives. One Sunday children from Riga were taken to Riga hoping that we might find someone we knew. We had an appointed place to meet in the evening, and I went walking along the streets. I went to our neighborhood, walked along familiar streets recalling my childhood. An older woman looked at me closely and asked, 'Are you Buna's daughter?' Buna was my mother's name. Everybody said I looked like her. The woman recognized me. She told me that my family had perished, but that my uncle Boris was alive. He had returned from the front. The woman promised to find his address, and take me there the following Sunday. She gave me her address, and the following Sunday my brother and I went to see her. We went to our uncle together. The reunion was joyful.

After the war Uncle Boris got to know that our family had been killed, and that my brother and I were evacuated with the camp. Our older brother Todres also came back to Riga. He was at the front during the war. The commander of his regiment heard that he could speak German and my brother became an interpreter at the headquarters. Our uncle and brother were looking for us. They never lost hope that we had survived, and we finally reunited. Todres also came to my uncle. We told each other what we had been through, talked about our dear ones and made plans for the future. Our uncle worked as a tinsmith in Riga. He remarried. His new wife was a Jewish woman from Latvia. Her husband had perished during the war, and she and her son were in evacuation. When my uncle married her, they rented two small rooms in a shared [communal] apartment 19. Boris wife's sister and her son also lived with them.

Boris told us about our uncle Hirsh. He was a very good tinsmith. Germans gave him orders, but later sent him to Germany. My uncle died of consumption in Germany shortly before the liberation in 1945. We don't know where he was buried.

I could hardly remember my parents' faces. All I remember is that they were tall. My uncle said that all I had to do to recall my mama was look into the mirror, but I wished I had my parents' picture. Our family pictures were gone. There were different tenants in our house after the ghetto was eliminated. They didn't preserve any of our belongings. My uncle found some acquaintances. They had their wedding pictures, and in one picture my parents were among other guests. There was no opportunity to make copies of photos at the time, but I remembered the faces of my parents and they were engraved in my memory for the rest of my life.

My brother had finished school by then. In Ivanovo he was called by the Russian name of Semyon, and after the war he continued to be called by this name. However, when receiving a passport, my brother had his name of Shleime indicated in it. I called him Shlemike affectionately. My brother and I were very close. Boris trained him in his vocation as a tinsmith. Later my brother started working in his shop. He rented a bed from a Jewish family.

Our older brother Todres changed dramatically after the war. I remember how kind and caring he had been before the war, but the war made him cruel. After the war he went to work as a leather worker. Leather workers earned well. Todres was young and wanted a good life. My brother and I were a burden to him. He had a family and had to take care of it. He was married to Uncle Boris wife's sister for six months. Something went wrong and they divorced. Todres married Sima Taiz, a very beautiful Jewish girl from Riga. They had a traditional Jewish wedding. In 1949 their son Isaac, named after our father, and in 1959 their daughter Bella were born. The first letter of her name repeated the first letter of our mother Buna's name. Todres believed that it was his duty to take care of his family, and we were mature enough to take care of ourselves. Perhaps, he had some reason...

After finishing the 7th grade I came of age to leave the boarding school. I moved to Riga. I stayed with my uncle for six months. I became an apprentice at the sewing factory in Riga. I also went to the 8th grade of an evening school. When my uncle's daughter was born, I helped his wife to look after the baby. However, I couldn't stay with my uncle any longer. There were five of us living in two small rooms, and when the baby was born, there was no space for a baby bed. I rented a bed from a family. I didn't stay long with those families. When their situation changed, I had to look for another bed. I became friends with my distant relative, my uncle's first wife Zhenia's relative. We were the same age, and our situation was the same. She helped me with my luggage, when I had to move to another place, and I helped her, when she had to move. I was pressed for money. Apprentices received 30 rubles of allowance. I paid 15 rubles per month for the bed, and it was difficult to make a living on 15 rubles, particularly after the war, when there was a lack of food. When I started working, I didn't earn much either. I was just a beginner, and was paid based on a piece-rate basis. Life was hard, but I knew I could only rely on myself. I joined the Komsomol 20 at the factory. I was an active Komsomol member and participated in all events. After finishing the 8th grade I couldn't afford to continue my studies. I had to earn my living. There were many Jewish, Latvian and Russian employees at the factory, but there was no anti-Semitism.

In 1948 the cosmopolitan trials [see campaign against 'cosmopolitans'] 21 took place in the USSR. I remember this period, though it had no effect on me. I was a seamstress' apprentice and was far from politics. However, all of us knew that this was a struggle against Jews. According to our newspapers all cosmopolitans were Jews. The trial against cosmopolitans was followed by the Doctors' Plot 22. However, I had too many other problems to take care of: I had no place to live and at times no food. This was scary.

When Stalin died in 1953, I took it as a personal disaster, as if it were the end of the world. Actually, I grew up in children's homes where children were raised as patriots. Our tutors called Stalin the 'father of all people' and 'Stalin is our sun.' They must have been sincere having grown up in the USSR. This had been hammered into their heads, and they, in their turn, were hammering this into our heads without giving it much thought. I cried after Stalin, our chief and teacher like all others did. After the Twentieth Party Congress 23, where Khrushchev 24 denounced the cult of Stalin and disclosed his crimes, I cursed Stalin. How much grief this man had brought to people, and how much more he would have caused had he lived longer! People were returning from exile [see Deportations from the Baltics] 25, and their stories proved the truth of what Khrushchev had said. The processes against cosmopolitans and the Doctors' Plot meant to unleash anti-Semitism and nobody knows what it might have resulted in, maybe even in Jewish pogroms. After the Twentieth Congress we had hopes for some improvements. It was like taking a breath of fresh air, but some time later everything was back: the poverty and lack of human rights for common Soviet people, anti-Semitism. Only repression was in the past. I also understood that this open and aggressive anti-Semitism was brought to Latvia by those, who arrived in Latvia from the USSR after the war. They felt like they owned our country. They were used to anti- Semitism, which existed in Russia during the tsarist or the Soviet regime.

In 1957 fortune smiled on me. Uncle Boris' wife found a room in a shared apartment for me. There were no shared apartments in our country before the USSR. There were 8-10 square meter servants' rooms in all bigger rooms, and I was to get one such room. When I came to the executive office [Ispolkom] 26, where the housing commission was to decide whether I should have this room, I was so scared that I was shaking all over. However, they took a positive decision, and I lived in this room for 17 years. From the moment I moved into this apartment I faced Russian anti-Semitism. The tenants in this apartment were a Jewish family and a Russian woman and her son. They had arrived from Siberia. When I just came in there without my belongings this woman began to shout that zhidi were buying everything and that they believed that everything there was for them, but that I would never have this room. Anyway, there was nothing she could do about it. I had an order and I moved into this room. My uncle refurbished it and bought me some furniture. The Russian woman continuously made scandals with me and with the Jewish family. She even dared to fight with us.

I became a good dressmaker and was offered a job in a shop. They offered a bigger salary and I accepted the offer. There were Jewish employees in the shop. They spoke Yiddish to one another. I had forgotten the language when in the children's home, but when I came to this environment, it took me no time to restore my language skills.

My brother and I celebrated all Jewish holidays at my uncle's place. He observed Jewish traditions and celebrated Jewish holidays. His wife was very religious. There was a lack of food products after the war. At one time there was even the system of food cards [Card system] 27, but whatever the situation, Boris' wife followed the kashrut. She bought kosher meat and sausage from a shochet. She bought live chickens at the market and took them to the shochet. They celebrated Sabbath on Friday. Saturday was a working day in the USSR, and my uncle had to go to work, but his wife didn't work on Saturday. They also celebrated Jewish holidays according to all rules. She also baked matzah for Pesach. The synagogue in Riga was open in the postwar years. It was amazing that the Germans didn't ruin it. Perhaps, it was because it was hidden behind apartment houses. The Germans burnt a number of synagogues in Riga, and later the Soviet regime closed the remaining synagogues. They didn't remove the synagogues, but instead, they used them as storage facilities or even residential quarters. However, this one survived. Even on weekdays it was full, and on holidays, such as Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur or Pesach, there wasn't an inch of room inside. There were people crowding outside. My uncle's wife had a seat of her own, and she paid for it each year. There was a beautiful choir and a wonderful cantor. We went to the synagogue on all holidays.

I got married in 1961. I met my future husband, Samuel Goldshmidt, at work. He was a tailor and worked in the shop. I made women's overcoats, and Samuel made men's wear. Samuel came from Daugavpils. His father, Hirsh Goldshmidt, was the best shoemaker in Daugavpils, and his mother, Basia, was a housewife. Besides Samuel, they had a son, David, and two daughters, Paya and Frieda. All children looked like their father. They were tall and had fair hair. Paya, the oldest one, was born in 1923, and Samuel was born in 1924. Frieda was born in 1925, and David was the youngest child. They grew up in a traditional Jewish family. The children were raised to respect Jewish traditions. After finishing cheder Samuel went to the yeshivah in Liepaja. Samuel can read and write in Hebrew well. One day a hooligan threw a brick and hit Samuel on the head. Samuel survived miraculously, but he asked his father to take him home. He went to a general education Jewish school and after finishing it became an apprentice of a tailor. His brother David was also a tailor. They spoke Yiddish in the family. None of them knew any Russian.

When the war began, Samuel's father went to the front, and the family evacuated to Irkutsk. Samuel was regimented to the army in 1943. He was at the front and had several awards: an order and a few medals. Samuel's father perished at the front. His mother became a widow at the age of 48. She never remarried. Basia was a very energetic woman. She raised four children alone and managed to give them a start in life. After the war the family moved to Riga. Samuel's sisters got married. Paya's marital name was Zilber, and Frieda's marital name was Benhen. Paya had two daughters, and Frieda had a son, Hersh, named after the deceased father, and a daughter. Basia lived with her younger daughter. David was the first to move to Israel in the 1970s, during the mass emigration of Jews. He got married in Israel and had two daughters. David was very kind, cheerful and witty. He was well-loved by all. He died of cancer prematurely. Samuel's sister and his mother also lived in Israel. Basia lived a long life. She died at the age of 90. Samuel's older sister Paya died in 2003. Paya and her husband loved each other very much. She used to say that if he was the first to die, she wouldn't be able to live without him. Paya died first. Her husband had cancer, and refused from medical treatment. He didn't want to live without her. He died one year after Paya. Frieda and David and Paya's children still live in Israel.

We had a traditional Jewish wedding. My husband and I grew up in respect of Jewish traditions, and followed them even during the Soviet regime. I was an orphan, and my uncle told me he would arrange the wedding for me. It was a beautiful wedding. There were Jewish musicians and a rabbi. The wedding took place at his dacha 28 in Majori, at the seashore. There was a big party in the hall, and a chuppah in the yard. There were many guests at the wedding party. After the wedding my husband moved in with me.

In 1962 our son Boris was born. We named him after my mama, by the first letter of her name. His Jewish name is Boruch. He had his brit milah according to the rules. Following the Jewish tradition, we did not cut his hair before the age of three, and at the age of three we arranged the upsheren ritual, the first hair cut. He had long fair hair and was often mistaken for a girl. He didn't quite like it and was happy to have his hair cut short.

We spoke Yiddish at home, and my son knows Yiddish well. My husband taught him Jewish traditions, history and religion. We always celebrated Jewish holidays at home. I didn't have as much time as my uncle's wife to prepare for holidays, though. My husband and I worked, and I had no time to stand in long lines to buy food products, but I did my best. We always had matzah at Pesach and no bread. We went to the synagogue on holidays and took our son with us. My husband and I often recall beautiful services on holidays and how beautiful the choir was. When in the 1970s local Jews started moving to Israel, fewer people were coming to the synagogue. [Editor's note: according to the 1970 census, the Jewish population in Riga constituted 30,581 people. The population in Riga went down due to Jewish emigration to Israel and other countries: in 1979 to 23,583 people, and by 1st January 1989 to 18,814 people].

There were only newcomers left, and they didn't observe Jewish traditions. This wasn't their fault. They had grown up under the Soviet regime, when there was a ban on religion [see struggle against religion] 29, when everything of Jewish origin was extirpated from their life. An acquaintance of mine, who came to Riga from Russia, told me that they were even afraid of teaching their children Yiddish. Her grandmother spoke Yiddish, and her mother already didn't know it. Also, only older people, who had no fears left, went to the synagogue. Younger people didn't attend the synagogues for fear of losing their jobs. They were not to blame. The Jewish religion and traditions have always been a part of our life in independent Latvia before 1940 or even during the period of the Soviet regime. My son and I sat on the upper tier at the synagogue, and my husband sat on the ground floor. When our son grew older, he stayed with his father at the synagogue.

We didn't celebrate Soviet holidays at home. We were happy to have another day off, though. I liked parades on 1st May and 7th November, when people got together for the parade and for parties after the parade. We drank a little and then sang songs. We had lots of fun. Then we went for a walk with our son and visited our relatives on every other day off.

My brother Shleime, a tinsmith, married Ida, a Jewish girl, in 1954. He also had a traditional Jewish wedding. His wife was born in Liepaja in 1934. Her parents had nine children. During the Holocaust the family was in evacuation and they all survived. Ida's mother sent her children to the children's home fearing that she wouldn't be able to provide food for all of them. After the war they moved to Riga. Ida told me that during their evacuation, when they were running along the streets of Liepaja to the railway station, Latvian residents kept shooting at them. They had often killed Jews even before the Germans came to the country.

Their son Boris was born in 1955, and their daughter Hana, named after Grandmother, was born in 1960. Boris was named after our mama, by the first letter of her name Buna. In 1971 my brother and his family emigrated to Israel. It was very difficult to obtain a permit to leave the USSR, and Ida and other Jews from Riga, who were refused such a permit, went to Moscow to insist on getting the permit. They went on a hunger strike in front of the Supreme Soviet 30 of the USSR, and they finally managed to obtain this permit to move to Israel. However, they only stayed in Israel for three years. My brother could hardly cope with the climate in Israel. He and I have problems with joints resulting from our hard childhood in the children's home. The disease recrudesced in Israel, and my brother had problems walking.

Ida decided they should move to Germany. My brother hated the very idea, and they argued so hard that at times they were on the edge of divorce, but my brother couldn't leave his wife and children. They moved to Berlin. They have citizenship of Israel and Germany. My brother had a hard time at the beginning. It had to do with his work considering that there were different technologies and different materials, but also, he suffered from living in the country, whose citizens had been exterminating Jews. I know that this wasn't so hard on his wife: her family survived in the Holocaust and none of them was murdered or burnt. Besides, she is five years younger than my brother and she doesn't remember all of these horrors. It was hard for my brother. Later my brother made friends with a Jewish shoemaker from Latvia, who taught him his vocation. My brother went to work in his shop and began to earn well. He supported me since he went to Israel. He sent parcels via Joint 31, and also sent money occasionally, when someone traveled to Latvia. A few years later his partner decided to move to his daughter in Canada. He sold the shop to my brother just for peanuts. My brother has lived in Germany for 30 years. He adjusted to living there and it is easier now. Shleime and his family observe Jewish traditions. His daughter is married to a Jewish man, and his son has a Jewish wife. My brother has grandchildren. Shleime was very upset, when our niece Bella, Todres' daughter, married a Latvian man, and his son's second wife is Russian. Shleime loved our brothers' children. He didn't criticize them, but he suffered a lot. However, Bella and Isaac have very good families, and I'm very happy for them and wish them happiness.

We still lived in our small room. We suffered from continuous attacks of our Russian neighbor. She was really a sadist. We spent summers renting a summer house in the vicinity of Riga. For ten years we were on the lists of the executive committee for getting an apartment. We knew that a bribe given to those officials who were responsible for the distribution of apartments would have accelerated the process, and once somebody even gave my husband a hint in this regard. However, we didn't have any extra money, and secondly, my husband would have never done such a thing. So we waited patiently till it was our turn to receive an apartment, until there was a vacant apartment available in the suburb of Riga. It was rather shabby and had stove heating, but we gave our consent to have it. Our son was 13, when we moved in there. There were two rooms, and we were quite content about it.

During the mass departures of Jews to Israel in the 1970s my husband and I also decided to move there. His relatives and my brother were moving. My older brother Todres and Uncle Boris were also going to move to Israel, but none of them obtained a permit from the Soviet authorities. My uncle had two refusals before he was allowed to leave with his wife in 1991, when Latvia became independent [see Reestablishment of the Latvian Republic] 32. They've lived in Israel for almost twelve years. Todres was severely ill in 1991 and could not relocate. He died in 1992. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Riga. His wife lived five years longer. She was buried beside Todres' grave. His son and daughter live in Riga. They have grandchildren. We occasionally see each other or talk on the phone. However, at that moment we were hoping to leave with our relatives. We wanted to be near our dear ones, and we couldn't even imagine staying here. Unfortunately, this was not to be. I developed a severe heart disease. We had to call an ambulance several times, and once I was taken to hospital. Then I was appointed for a pension for disability and the doctors advised me not to change the climate. We could not relocate. Our son often rebuked us for staying, but what could we do...

After finishing the 8th grade of his general education school my son entered the technical school of light industry. After finishing it he wanted to continue his studies at a higher educational institution, but he also wanted to learn a vocation and go to work. When a student of this technical school, my son fell in love with a Russian girl. There were no Jews in our neighborhood, and there was not much choice. The girl also loved him, and she was beautiful, but I couldn't even imagine letting her into our family. When Boris told me he wanted to marry her, I was outraged. We had a Jewish family and had our traditions and a non-Jewish woman coming into our family was out of the question. My husband was also flatly against it. We told Boris that if he married her, our family would be his no longer. I don't know what Boris told his girlfriend, but they broke up. Later she got married and left Riga with her husband. My son developed a terrible depression. He used to lie in his room staring onto the ceiling without talking to anybody in the evenings. It was hard for him, and I didn't know how to help. Later he recovered.

Boris met his future wife at the synagogue 20 years ago. We went there on Simchat Torah, and my husband's acquaintance suggested that we introduced Boris to a Jewish girl. We were positive about it, and she came back with a beautiful Jewish girl. We liked the girl. Our son also liked her. They started seeing each other. My daughter-in-law's name is Sophia. Her maiden name was Taiz. She came from the town of Rezekne, 300 kilometers from Riga. Sophia's mother died, when the girl was eight. Her father was a construction foreman. He was busy and couldn't spend much time with his daughter. She was raised by her aunt, a philologist, a teacher of upper secondary school. Now Rachel, my daughter-in-law's aunt, is the chairwoman of the Rezekne Jewish community. After finishing school Sophia came to Riga where she entered the Faculty of Physics and Mathematic. She lived in a dormitory. When my son and Sophia got married, she moved in with us.

In 1986 our granddaughter Lubov was born. Sophia was in her last year, and I took responsibility for taking care of my granddaughter. I wanted Sophia to continue her studies and defend her diploma successfully. My son was a crew leader in a big woodwork shop. He also studied at the extramural department of the Riga Polytechnic College. I looked after my granddaughter, and when my husband came home in the evening, he took her out for a walk. Of course, it was difficult for us, but we wanted to help our children. When Sophia received her diploma, her father visited us and said that Sophia wouldn't have graduated from university if it hadn't been for our assistance. It was true. I get along well with my daughter-in-law, but I think children and parents shouldn't live together. It's hard for different generations to get along. However, we had no conflicts living three years together. My son worked hard, and they saved money to buy an apartment. My husband also earned well, and we supported them to help them to save more. During perestroika 33, when it was allowed to have one's own business, my son and his partner rented an office and opened their own woodwork company. There are five of them working there and they are doing well.

Perestroika enabled us to receive an apartment. According to a decree of Gorbachev 34, veterans of the war were allowed the privilege of building cooperative apartments. My husband submitted a request, and two years later we received a two-room apartment in our building. My son and his wife stayed in our old apartment. Our granddaughter stayed with us on weekdays. On Friday evening her parents picked her to take her home for the weekend. We have a wonderful granddaughter. Of course, we wanted them to have another child, but it didn't work out. My son said he had to provide for the daughter, and wanted her to have everything she needed, but that he didn't want to have anther child to live in poverty. There is a Jewish saying that each child comes into life with its own fortune. My granddaughter went to the Jewish elementary school. She only had the highest grades in all subjects. Her Hebrew teacher always complimented her. I was so happy to hear this! My granddaughter was also a kind child and got along with all children. She went to a good gymnasium after finishing elementary school. My son and his wife earned well to pay for her studies.

Lubov studied very well and took part in Olympiads. She even went to the all-Union Olympiad for schoolchildren in Moscow. When she finished school, my son received a letter of appreciation of his good care of the girl issued by the school management. That year [2005] my granddaughter entered the Faculty of Economics at the university. The competition was high, but she was successful. My son and his wife also pay for her studies. Sophia is chief accountant in a company. She earns well. My son is also doing well. There is a lot of competition, but thank God, my son can provide for his family and support us. My husband and I are pensioners, the poorest people in present-day Latvia, but our son helps us to feel more comfortable than other pensioners. My son has fewer orders these days, but we hope for the better. We have to hope that he will have new customers soon.

Our son and his wife often visit us. My son remembers Yiddish and speaks Yiddish with us. My daughter-in-law does not know Yiddish. Rezekne was a Jewish town before the war. There were 13,000 Jews in it. They were exterminated during the war. Now the Jewish community of Rezekne accounts to 35 people, and my daughter-in-law's aunt is the only native resident in the town. A few years ago there were still about 100 Jewish residents there, but some of them passed away and the others emigrated...

We celebrate Jewish holidays at home. My husband and I go to the synagogue, and then our children visit us and we have a festive dinner. Sophia has no time to cook a big meal, and I am so happy, when our big family gets together at the table.

Gorbachev's perestroika was not only good because we received an apartment. We felt the freedom, and that was important. We also were allowed to correspond with our relatives abroad, visit them and invite them to visit us. I haven't been to Israel due to my health, but my husband has visited his relatives several times. He will go there again soon. We wouldn't even dream about anything like this, if it hadn't been for perestroika.

I was positive about the breakup of the USSR [1991]. I think this was the right thing to happen. Each republic needs to live as it wants rather than being directed by Moscow. My husband is also happy about it. There has always been anti-Semitism in Russia. During the Soviet times we heard so many times from visitors from Russia that zhidi were to blame for everything. Even if Jews never did anything bad to them they would continue to blame Jews for all their misfortunes. Rude and uneducated people don't hesitate to blame others for their problems since it's much harder for them to recognize their own faults. Even visiting Jews dislike local Jews. Every now and then I asked them what was so bad about local Jews. One cannot say that all local Jews are no good. They are different. Same with visitors. There are bad and good people. My close friend moved to Riga from Zaporozhiye, and she is a wonderful person. One cannot judge all after having one bad experience.

I think anti-Semitism in Russia is getting stronger, but the most concerning fact is that it is not punished properly. If they beat a rabbi in the street or anybody looking like a Jew, if a Duma deputy can call people to do pogroms and remain a deputy, this is terrible, and I'm happy that our independent Latvia is so far from Russia now. Here, if a politician makes an anti-Semitic statement, his career would be over. One of the Seim deputies said once that Jews assisted the Russian occupational army in 1940. There was a huge response to his statement. The Jewish community of Latvia pronounced its protest. Latvians may feel apprehensive about the Jewish community. It's no secret that Latvians took an active part in the extermination of Jews. This deputy was dismissed from the Party and deprived of his deputy's mandate. So, if one fights against anti- Semitism, it can be destroyed. Of course, there is routinely anti-Semitism in Latvia. There have always been rascals. Once an igniting bottle was thrown into the synagogue. Then a police post was established near the synagogue, and also, cameras were installed. It was a good thing to do, but how come no church or cathedral need police to secure the people, and it's different with the synagogue? They also desecrated the Jewish cemetery. These boys were captured, and there were Russian and Latvian boys among them. I know that the community fights against such demonstrations and anti- Semitic rascals. I hope this struggle will be more successful now, that Latvia has become independent.

During perestroika the Jewish community, LSJC [Latvian Society of Jewish Culture] 35 was established in Riga. There was a Jewish choir organized at the charity center. I like singing and I joined the choir. There are native residents of Latvia and those who moved to Latvia later in this choir. We all love Jewish songs, and this unites us. We enjoy each rehearsal or performance. We often give concerts in Jewish communities of different Latvian towns. Sometimes it's hard. We are older people, and it's even difficult to stand for one and a half or two hours, but we forget about it, when we start singing. There are new people and new songs coming. We've become friends. We celebrate birthdays and Jewish holidays together. We need each other and those people, who come to our concerts to listen to Jewish songs.