Alina Fiszgrund

Cracow

Poland

Interviewer: Magdalena Bizon

Date of interview: March-August 2005

I met Mrs. Alina Fiszgrund in a former assisted living facility in the suburbs of Cracow. A former one, because, following the fall of communism in 1989, the tiny apartments were sold to the residents, leaving the cantina and the clinic at their disposal. Mrs. Fiszgrund moves with difficulty, as, because of her advanced diabetes, she has had part of her foot amputated. Our meetings take place to the rhythm of the consecutive insulin injections. Mrs. Fiszgrund is a hard-of-hearing person. To read, she needs a special flashlight-equipped magnifying glass, which she very much deplores. She is a delicate lady and finds many of our questions blunt. She is also a person who converses and explains her views with great eloquence, while making sure to avoid the specifics. During the first meeting I discovered that even happy childhood memories were painful for her. 'It's better to forget everything,' she told me. After meeting me thrice, Mrs. Fiszgrund's health suddenly deteriorated and she had to spend six weeks in hospital. Upon returning, she told me she wanted to stop the interview because remembering her loved ones is proving too painful for her. She agreed to continue talking about the family of her husband, whose brother, Salo Fiszgrund, was the last secretary general of the Bund.

I don't even have genuine documents, everything's misrepresented. I changed my identity because such were the circumstances. I was born in Ruda Pabianicka near Lodz [today a Lodz suburb], but my ID says Lodz, and my war- time fake papers state Przedecz [town 75 km north-west of Lodz] as my birthplace. The documents say I was born in 1921, but it seems to me it was a year earlier. I've been something of a globetrotter. I've lived in Moosburg [Przedecz's name under the German occupation], Wloclawek [city 100 km north of Lodz], Lodz, Vienna, Lebork [large town in northern Poland, 50 km west of Gdynia], Cracow, and Paris.

There was little talk about our ancestors. Where they came from - I don't know. I know that people write letters, do research and so on to trace back their ancestry. I was never interested in that. My family wasn't one with many children, and there were few relatives, few cousins. Of the grandparent generation, I remember only my mother's mother, and vaguely at that.

Grandfather Birnbaum, my father's father, was a lawyer in Piotrków Trybunalski [town 40 km south-west of Lodz]. I don't know his name, or his birth date. I think he died before World War I. From what I know, he had a brother who was a lawyer in Lodz. That brother probably had a son, but they are all dead, so why touch it? I don't even know how they died. I hardly knew them at all. I may have met them once or twice. My father's mother died delivering another baby when my father was seven. I know neither her maiden name, nor her first name. My father and his two brothers were raised by their mother's cousin.

My father's name was Towie Birnbaum [ca. 1890 - 1943]. His Polish was as good as his German and his Russian. He spoke Yiddish too, but seldom. He was born in the early 1890s, in Konin [city 100 km west of Lodz], which was then under German administration [there were three partitions of Poland, in 1772, 1793, and 1795, by the three neighboring powers: Russia, Austria- Hungary, and Prussia. Konin initially found itself in the Prussian part, and after 1815 formed part of the Kingdom of Poland, a limited-autonomy organism tied by a personal union to Russia. Poland regained its independence in 1918] 1. He lived in Petersburg, studied in Dorpat [then Russia, today Tartu, Estonia]. During World War I he served in the regular Russian army. That was before the Revolution 2.

Zygmunt, one of his brothers, was murdered during the Revolution, as at the time you only had to have the wrong political view to be executed. Zygmunt was a lawyer, an attorney-at-law, in Yekaterinburg [then Sverdlovsk], I guess. I know that, in the interwar period, my father made efforts to bring Zygmunt's family from Russia to Poland. His wife, who was Russian, and their two daughters. I think the Russian [Soviet] authorities didn't permit them to leave. I didn't know that part of the family at all.

Father's second brother lived in Piotrków Trybunalski. I don't know his name. I know he had children and that he was murdered during World War II. I don't know where, I don't know how, I suspect it was in Piotrków [the first ghetto the Germans organized in the occupied Polish territories, created October 1939, with 28,000 people inside, of which only some 1,600 survived].

My mother's father was a pharmacist. His last name was Wyler, and his first name, I guess, was Abe. Where he was born and when he died - that I don't know. His family came from Warsaw. Grandfather's father was a great expert in horses and I think he kept a stud farm somewhere near Warsaw. Grandfather himself completed three-year pharmacy studies, as that was how long it took, according to Gasiorowski's book on pre-war pharmacists. Grandfather had a brother who was also a pharmacist. I think he never married.

My maternal grandmother was nee Staft-Zofft [1877 - 1925]. It was a Swedish surname. But she wasn't Swedish, she was a Swedish Jew. I don't remember her first name. I know she had a sister, Sonia, who was handicapped. She was 'bucklig' [German: hunchbacked]. She died before my birth, I only heard about her. A chest lid reportedly fell on her because the maid didn't watch, and, as a result, Sonia had a 'Hochschulter' [German: high shoulder]. My grandmother died in Lodz, at the age of 48. I think it was 1925. I was four then, or something like that.

I remember my grandmother from photographs. An ascetic face. I remember vaguely that I liked to dress in her shirts. I'd also try her shoes on. The shoes of the period were high, up to the knee, laced up, and with very high heels. When I put them on, they were much too large for me. I couldn't make a step, and I was afraid I'd fall. I remember I tried the brown ones, I tried the black ones. And the shirts. And from early childhood I had a fondness for bead necklaces. I liked very much to wear them, to have something on my neck.

When my grandfather became a pharmacist, at first he operated pharmacies in small towns, to then gradually work his way up. That's how people did it back then. So first he had a business in Slupca [small town near Plock, 50 km north-west of Warsaw], then known under the German name of Stolp, where my mother was born. Then in Parysów [small town 50 km south-east of Warsaw], where the other children were born. Then my grandfather had a pharmacy in Lodz.

My mother's name was Perla, Perla Wyler [ca.1892 - died in the Holocaust]. She was two years younger than my father, so she must have been born around 1892. She grew up in Slupca and Parysów. I think she had a governess, as was customary for a middle-class home at the time. She was the pharmacist's daughter, so they weren't just anybody. I don't think she had official high school education, though she spoke several languages. She spoke German, French, Russian, Polish, and Yiddish as well.

Mother had two younger sisters. The middle one, Aunt Iwa [? - 1944], her real name was Iweta, I think, was a spinster, never married. She had a degree in pharmaceutics and worked in a pharmacy in Lodz. She also completed a musical school in Paris. She had a piano at home and played very nicely. It was a brand-name instrument, a Pleyel. During the war she gave the piano for safekeeping to a German family she knew, the Freygangs, and left Lodz. When the war was over, the Freygangs were thrown out, and their apartment was robbed.

After my aunt left Lodz, she settled in Warsaw. Not in the ghetto, she had Aryan papers. She had converted sometime during the Sanacja period 3, joined the Orthodox Church, and was officially of Orthodox religion. She lived on the Aryan side, and that was costing her a whole lot of money. Eventually she ran out of money and, shortly before the Warsaw Uprising 4, she moved to Lowicz [town 50 km west of Warsaw]. She still co-owned a chemical or pharmaceutical factory of sorts in Lodz, but by that time she had lost any contact with the people there. She rented a room in Lowicz, and there, in that room, she fell ill, and died. It's really sad to remember, she had lost everything by then, had no money, and, well, she wasn't old yet.

My mother's youngest sister, Klima [? - died during WWII], married a Polish doctor before the war, Mr. Donat Brzeski. She originally had a different name, but I don't remember it. As the wife of Mr. Brzeski she used the name Klementyna, Klima.

My father earned his degree from the University of Dorpat [Academia Dorpatensis, a university founded in 1632 by Gustav Adolf, King of Sweden; today Tartu, Estonia]. Which year it was, I don't remember. The lecturing languages were, if I remember it well, partially Russian and partially German. Aunt Iwa, my mother's younger sister, also studied in Dorpat. She was one of the first female students there. My father met her first, and that's how he got to meet my mother. I remember the story very well.

My parents married towards the end of World War I, in 1917 or 1918. It was a civil marriage, I guess. My father was a supporter of full assimilation. Only he wouldn't change his religion. That was his, let's say, 'Weltanschauung' [German for philosophy of life]. And my mother also had progressive views. It was a rather non-religious home. They went to the synagogue once a year. And the holiday dinners were, I guess, my mother's initiative. But she wasn't very religious either. Mother kept the house and raised the children. She always had a maid, and sometimes even two. On the other hand, a maid cost 15 zlotys a month before the war, someone once told me [a pair of good shoes cost 10-12 zlotys].

As far as her looks are concerned, my mother wasn't pretty. Not ugly, though, so-so, I'd say, but shapely and elegant instead. I have my mother's photo from the ghetto, but I never look at it. She looks tragically. The worst misery and poverty you can imagine. I have it somewhere, I even know where. But I never look at it. My mother died in Lodz. I heard it was in 1943. Father died in Wroclaw. I don't know which year and how. Well, that's life.

I had siblings. There were four of us. All girls. I was the oldest one. There was roughly two to three years' age difference between each next one of us, so we played together. I played with my sister, and then they... In 1939, when I was 18, the whole family got scattered. No one's left.

When I was little, we lived in Moosburg [Przedecz], where my father had bought a pharmacy. The first language I spoke was Polish. I know German well, and I can converse in French. I like the German language. It aids reflection. I like German literature. It is something I knew before, yes. The languages spoken at our home were German and French. There were guests you spoke French with. I also remember a landowner family, the Wiesers, with whom my mother spoke German.

My parents lived in three rooms. The first one, from the front, served as a living room, a dining room, and a guest room. There was a large table there, and a library, that is, a bookcase, a desk, and an armchair in which my father would sit when he had something to write. And a radio, which stood in the corner. The top-of-the-range model. The most expensive, most exquisite one available at the time. There were also paintings. None of those have survived that I know of.

I have a photo of myself, taken at home, when I'm three or four years old. I'm sitting on the table in a flower dress. I remember that dress. It was a white one, with colorful flower posy fancywork. The photo also shows the living room furniture. The next room was my parents' bedroom. In the back, looking out into the garden.

From the living room you entered into the pharmacy, because the apartment was divided by it, and the third room, the children's room, was beyond the pharmacy and beyond the backroom, where they kept the equipment and materials and prepared the medicines. There was a hallway in the back that you entered from the porch, and from that hallway there was a door directly to the children's room. But it was rarely used. The door was usually closed. As I remember it, you usually went through the pharmacy.

It was a small pharmacy, a rural kind of one. There was a single backroom, and the main room with a clock in the middle. The clock was large; you had to wind it every 48 hours. The walls were lined with cupboards with shelves for jars and bottles at the top and drawers at the bottom. The furnishings had been brought from Berlin, as Berlin was not far away [ca. 400 km].

I was always afraid to go through the pharmacy. I often wondered why I was afraid. It seemed to me something was clattering, shuffling in those drawers. Later, when I was older, I arrived at the conclusion there had had to be mice there. Not rats, certainly not, but mice, and it was them that frolicked there, making all those noises. And I also remember when someone died and I thought a ghost was visiting the house. But that was also a broader influence of the surrounding because I had girlfriends who would often speak about ghosts.

There was also this Mr. Arentowicz [Zdzislaw Arentowicz - man of letters, journalist, bookseller, bibliophile] who would visit our town from time to time. He was a bookseller by profession and kept a bookstore, but he also wrote poems about the region. And I remember that he also inspired those séances. Invoking ghosts was something that the Catholics did, I never heard of Jews doing it. Even in those homes that were in flavor of assimilation they wouldn't hear about it. I remember that when Pilsudski 5 died, there were whole companies of people in Lodz who'd gather to invoke his spirit. I had a friend in Lodz in whose home those séances were held very often and I was simply afraid to go there. Janka Kozlowska, her name was, a beautiful girl.

When I was little, I had all the toys I could dream of. I was very fond of dolls. I had pretty ones. Girlfriends would visit me, kids from the neighborhood. I played with them. I was about eight when I got a tricycle. I vaguely remember that. Near our house there was a field where soccer matches were played. And when no game was taking place, I'd go there to ride my bike. There was also a large yard and a porch at the back of the house where you could play. The porch was unglazed, made of wood, so on sunny days it was very nice to sit there. On rainy days, you had to be careful, because, sitting at the edge, you could get wet.

There was a large garden by the house, but in that garden there were hares running around, and rats... Because at the far end of it was a cellar. Country houses used to have such dugout cellars, you went down the stairs there. Sour milk, for instance, was beautifully done there. If you took it out from there in the summer, it'd be cold and so thick you could cut it. But there were also rats in those cellars. I know you had to put out rat poison, I remember that. Sometimes if I saw a rat there, I thought it was a marten. And for a long time I mistook the rat for the marten. The rat has a long, bare tail, whereas the marten has a short one, and it's furry. I was terribly afraid of rats. But sometimes, when I thought it was a marten, I'd call it. The marten, when called, came to you, but the rat didn't. Perhaps the martens were domesticated...

The garden was large and very nice. There were many kinds of fruits there, there were apples in that garden, and there were cherries. I remember how they shook those cherries. At the far end lived the gardener. His first wife had died, and he married again, and they had a new baby each year. His wife carried water to the nearby houses using a special yoke. They were very poor. She was still a young woman. She would deliver the baby, and two or three days later she'd already be carrying the water. The sight of that woman carrying that yoke was horrible. I don't know what happened to them.

As far as the holidays are concerned, I remember them, but I didn't pay much attention to that. At home, we observed Pesach, as well as Yom Kippur, to remember the departed ones. I never dressed up for Purim. I never felt drawn to that. But I remember the masqueraders. That's a nice tradition.

For Christmas, we had a tree at home. The tree was large, beautiful, with an arrow on top, and full of decorations. For us kids, the tree was an attraction. I remember that you opened wide the door from the pharmacy to the living room, and there stood the tree. During the Christmas season, the tree attracted people. It was a propaganda thing [marketing gimmick], to make people visit the pharmacy, if only to see the tree. It was for the public [the Przedecz population was made up by Poles, Germans, and Jews, who represented 20 percent of the overall population; there was one pharmacy for everyone]. In Klodawa [9 km from Przedecz], there was another pharmacy, owned by the Lewandowski family. Well situated, on the [Warsaw- Poznan] road. That was our competition.

I liked seder the most, because I love the Haggadah tune. This is the prayer you recite during the seder dinner. There are verses you recite, and verses you sing. I even have the Haggadah text in Polish. In the area where we lived, the traditional seder dish was stuffed pike. They took out the intestines, boned it, mixed everything, and added spices. They added onion, salt, pepper. Then they cooked it and put it on a platter. Whole, because they cooked it in an appropriately large pot. It tasted very good.

I haven't eaten stuffed pike for a long, long time, because here in Cracow they don't know how to make it. Here in Galicia 6, they make the carp and they believe this is the Jewish art fish. This isn't true, because stuffed pike was also a Jewish dish. Another version was pike in jelly. There was always gefilte fish at home, and carp. Besides the fish dishes, there were also various kinds of cakes, and a lot of eggs. Because on Pesach, when the seder evening starts, the first thing they serve, are eggs. Lots of eggs, whole platters of it, and you can eat as much as you want. They also served kosher beef ham. The more delicate variety, I think it could have actually been veal. Kosher ham is from the front part, because the back isn't kosher.

And on Pesach you eat matzot. You don't eat bread, but matzot. Where we lived, they baked them in the oven themselves. Those were rolled out matzot, they were thick, round, sort of fleshy. The dough wasn't rolled out equally. I saw how they did it, how the women rolled out those matzot. Then they put that rolled out dough on those wooden shovels, like the ones you use for bread, only wider ones, slid them into the oven, and then took them out very quickly, already baked. There was a special basket at our home that was used solely for storing matzot. And when the holiday was over, the basket would be put away into the attic. In Lodz, there were special bakeries, Jewish ones, that baked matzot. On Poludniowa Street. Like today, the matzot were packed in one-kilogram packs, only the packs were larger. Because the matzot - they were different than the ones of today.

After the war, those customs weren't observed at our home as much as they should have been. My husband and I didn't observe any holidays. The fact that I liked the Haggadah so much caused me to attend seder each year at the Jewish community center. This year I didn't go, but last year I was there.

Before the war it was only poor people who went for seder to the community center, but after the war that changed. Before the war, seder was organized for people who were religious but poor, who couldn't afford to eat eggs on that night, all those good things, the fish. Though in fact the fish had to be at every home. Everyone would spend their last money but the fish had to be there.

They organize it very well at the Cracow center, everything's all right, but these days, it's quite different than it used to be. In the past, when Mrs. Jakubowicz [Rozalia Jakubowicz, called the 'Mother of the Community,' mother of the incumbent community chairman, in retirement now] was still in charge of preparing seder, they served beef hams. These days they serve canned turkey. The fish isn't fresh either but comes from a can. And they serve square matzot, baked in a state-owned bakery in Israel. I have the square ones at home [prior to Pesach, the community distributes kosher matzah].

And here the Haggadah is sung by a man who is ninety years old. He screeches rather than sings. And the young man who responds to him, screeches too, he obviously learned it that way. There [in Przedecz], the Haggadah was sung by young boys, by children, and here it's an old man. And an old man, even if he had the best voice, will be screeching, not singing.

When I was a child, I liked virtually all dishes. The only thing I didn't like was chulent. That was prepared for Saturdays. I ate it from time to time, but it's heavy food. Jewish cuisine is rather fat. Before the war, they made everything with goose fat. One thing I liked to make for myself was 'Matzenbrei' [German for matzah mash]. You put the matzah into water for a moment to soak. Others simply poured water onto it. Then you put it on eggs mixed with salt and pepper, and fried all that in fat in a frying pan. We used to eat that with my husband, it's good.

There [in Przedecz], there were some Jews, but there were also many Germans, and there were Poles. There was no ethnic hatred whatsoever. That hatred only broke out later. Everyone spoke German there, because the place was close to the German border. So there was no communication problem. In the Pomerania region, the Jewish middle class was very pro-assimilation and very pro-German. Hitler's rise to power 7 came as a great shock for those people. But the interpersonal relations started deteriorating only around 1933-1934.

It was at that time, if I remember well, that the Przedecz Germans started going to Germany for some kind of training courses. They must have been brainwashing them there, because they came back all swaggering and arrogant. I know that also people with Polish names went there, though they must have obviously had some German roots. There were some Endeks 8 in Przedecz. The shoemakers, Poles. The so-called Nationalists. But those Endeks only raised their head around 1933-34, when the Germans started going to Germany for those brainwashing courses. That was taking its toll on the whole community.

Things were getting tighter. In a small town, where everyone knows everyone, one stands out. So we moved to Lodz, which was a large city, and there you got lost in the crowd. So, two years before the war, I lost touch with Przedecz. I remember it until roughly 1937. [Editor's note: the Birnbaum family sold the Przedecz business in 1937 and moved to Lodz. They had been trying to move out for several years before, which is why they sent their daughters to schools elsewhere, first in Wloclawek, where they planned to move, and then to relatives in Lodz].

Jews had lived in Przedecz for a long time [ca. 600 years; the Yiddish name of the town was Pshaytsh]. The town had a very nice synagogue. A beautiful wooden baroque building, with superb paintings. An unforgettable interior. It was an architectural monument. The literature states that the most beautiful wooden synagogue in Poland was the one in Tykocin 9. This isn't true. The Tykocin synagogue that some writers fawn over so much, was nothing compared with the Przedecz one. It was so beautiful! Mr. Zemelman was the rabbi there. A relatively young, intelligent man. When the Germans came, they set the synagogue on fire and forced him to sign a statement that he had set it on fire himself. Everything burned down.

There was a whole Jewish quarter in Przedecz, there were Jewish stores. I remember a Mr. Sochaczewski who ran a cooperative bank and a textile store. He sold good-quality wares. His daughter studied in Grenoble, so they couldn't have been such simple people. He was one of the first to die. There was a doctor. He fled. And there was a watchmaker. He was running away, but this guy, a Pole, blew the whistle on him, and the Germans caught him and murdered him. And, in the end, he wouldn't have been a nuisance to anyone if he had survived.

I wasn't there but I heard after the war that one day there came the 'death trucks' [trucks where people were killed using the exhaust]. There came those trucks, they packed them with people, and they took them all away to Dabie on Ner [30 km from Przedecz, 6 km from Chelmno]. That was quite a distance to cover. When they took them in the evening, they drove almost for the whole night. Well, almost until dawn. And someone told me that when those cars arrived in Dabie, they started throwing out the corpses right away. That it was all done 10.

It was a small town, but there were three doctors there. That was a large number, I guess, as I knew places where there was only one doctor. But in Przedecz, prior to the war, there were three. I don't know, perhaps each ethnic group had its own. There were all kinds of stories related to the 'bris' [brit, circumcision]. I was already grown up enough to understand that, and there were all kinds of stories.

The bris was performed not by the rabbi but by the shochet, according to the laws it is the shochet that performs the operation. [Editor's note: in fact, it is the mohel who carries out the brit milah.] He removes the foreskin, and then should suck out the blood. Those were often, given the prewar realities, as I saw them, so those were often rather uneducated people. Not all of them, certainly not. But I guess that's why there were frequent cases of circumcision-related infection. There, in the Pomerania area. Either there was something wrong with instrument sterilization, or the infection took place during the blood sucking. In Lodz such things rarely happened.

Such patients never went to the pharmacy for medicines. Though this may sound strange today, that's how it was. After all, such an infection could even result in death. Sporadically. But such a child was already weaker. I guess they sprayed Dermatol [disinfectant powder] over the wound.

Scrofula was another frequent disease [tuberculous infection of the skin of the neck]. Awful. Those were the lowest classes, the really poor people. Babies got born that way, already with the scrofula condition [points to the neck under the chin]. Though I also saw old men with scrofula. Trachoma was also horrible [contagious granular conjunctivitis]. Those babies were often born with innate trachoma and were blind virtually from their birth. And those eyes, all bloody, looked terribly. You don't see that kind of thing today.

I didn't go to elementary school, I had a teacher at home. That was a frequent practice those days, still popular when I was young, that people took a teacher. The teacher taught you, and at the end of the school year you took an exam at the public school and either you passed the year or you didn't. That's what it was like.

Then I successfully passed entry exams to a school in Wloclawek. I went to gymnasium there, because my father wanted to buy a pharmacy in Wloclawek. He was negotiating with the owner, Mr. Goworowski. In the end, they failed to reach an agreement, and someone else bought that pharmacy. I guess he wanted a lot of money. Too much. My father didn't have that much. That Mr. Goworowski went to Casablanca and opened a pharmacy there.

I also remember, in Wloclawek, on Cyganka, there was a street of that name, there was a pharmacist, Dziewanowski, who used to say 'my palace pharmacy...' And indeed, everything was so highly polished there. The pharmacists are also history. Prewar pharmacists had their traditions. Today, it seems to me, those traditions are gone. The pharmacy world is not as it used to be.

Wloclawek was a nice town, situated on the Vistula, observant of traditions. There was even a Jewish gymnasium there, a coeducational one, but I went to a public one, the Maria Konopnicka Gymnasium. On Stodolna Street, near the Vistula. I went there for two years, to a French-language class.

I have a photo of myself from that time, dressed in the school uniform. It must have been taken about a year before the Jedrzejewicz reforms [Janusz Jedrzejewicz, 1931-1934 minister of education, author of 1932 school system reform], because the uniform has the sailor collar. The reform abandoned the sailor collars and introduced the so-called Slowacki collars instead. The pre-reform gymnasium had eight grades, and the reform introduced a four- grade gymnasium and a two-year high school, while the former first and second grades were made part of a five-grade [Editor's note: in fact six- grade] elementary school. I went to gymnasium about two years before that reform.

The headmaster of the Stodolna gymnasium was an eccentric lady, Ms. Degen- Slusarska. She taught us math. I have very unpleasant memories of her. I didn't like her, and I guess she didn't like me either. She was a large, strapping woman, of the masculine type. She was a great enthusiast of Gustaw Morcinek [(1891-1963): writer, former coal miner, wrote stories describing the life and work of coal miners in the Silesia region]. She'd invite him several times for reading evenings, and Morcinek would lecture us about the hard life of the coal miner.

In Wloclawek I lived in private lodgings, 'stancja,' that's what the term was, I don't whether this is how you call it these days. My first lodgings, if I remember correctly, were with my mother's friends who lived on Brzeska Street and had a beautiful garden. They grew only roses there. Various species of roses. There were several of us living there, girls of various ethnicities. There were Russian girls, two girls, I guess, were Orthodox. Various religions. It was, as I'd call it, a very international home. But I lived there for a short time only because my mother got unhappy with something and took me away from there.

My second domiciliation was with Baroness Szablowska, in a villa on Karnkowskiego Street. It was a very nice place. And it was also a place with traditions, where they taught you good manners and made sure you observed them. That was a completely different home than the first one. And a very religious one. She was a teacher. Her husband, a man well advanced in age, took us for walks, usually across the old bridge on the Vistula in Wloclawek. That bridge was at least one kilometer long, and when you crossed it, you were already tired, and you still had to go back. The bridge led to a suburb called Szpetal. To the left was a sugar plant, and to the right was a beautiful forest.

Then I returned home. Perhaps those lodgings were expensive. In any case, there wasn't much talk about money at our home. I was also ill with something. I had a female teacher at home, and then a male one. Tutor, the name was then. He taught me at home, and at the end of the school year I took exams at the gymnasium, the Konopnicka. That was a year, or year and a half, of a kind of indeterminate stupor, after which I left for Lodz. I have very, very fond memories of Lodz. That was the growing-up period.

Lodz was Poland's second largest city. It had neither a sewage system [between 1925-1939, some 71 kilometers of sewers were developed in Lodz, hooking up 2,700 buildings], nor a university. It had the Wszechnica Lodzka Academy [founded in 1928] but that was below university level. But it was a wealthy city [called the Polish Manchester - major center of textile industry]. There were tycoon families like the Plichals. They were German, I think. They made tricot clothing, and it was Lodz's only, and likely Poland's largest, plant of the kind.

Lodz's main street is Piotrkowska. At 100 Piotrkowska Street there was the Café Esplanada. When, on passing it by, you peeked inside through the window, it was a genuine fashion show. You saw how the women were dressed. The crème-de-la-crème elegant women met there. No question Lodz was a wealthy city. But was it so very elegant? It seems to me Warsaw was more elegant than Lodz, but Lodz was very colorful.

You could walk down Piotrkowska in broad daylight and see the Hassidic Jews 11, with the payes and all. If you were rich, you had your private hairdresser who came to your house and dressed your payes.

Lodz was such a colorful city because it had four major ethnic communities. On the one hand, there was the synagogue, and a few steps away - the Orthodox church. The Orthodox church stood either at Sienkiewicza or Kilinskiego Street. I don't know whether it's still there. The German community had its evangelical cathedral on Wolnosci Square. For the Poles, it was like that: if someone's a Catholic, they're Polish, if someone's an evangelical, they're German.

I remember there were stores in Lodz where they greeted you in German. There was a store selling sewing accessories on Piotrkowska between Glowna and Nawrot Streets. I don't remember the owner's name. 'Hier spricht man Deutsch' ['We speak German.'] said a sign right in the front window. That was before the war.

The Old Town in Lodz was where the Jewish quarter was located. A run-down and poor neighborhood. There was a street called Nad Lodka. Lodka was the creek on which Lodz was situated, one you could cross on foot, tiny and very shallow. A street called Zgierska led to the Wolnosci Square, and that was already downtown. But Zgierska itself, up to Ogrodowa, was just a slum, lined with those miserable little stores. The whole area was really very poor. The same was true for Franciszkanska, part of which was later included in the ghetto 12, where there wasn't a single two-story house.

The Old Town spoke Yiddish. The upper classes, in turn, were assimilation- oriented. Of Lodz's Jewish factory owners, the Poznanskis were a leading pro-assimilation family. In fact, they spent most of the time abroad, as in their palace on Ogrodowa [which after 1919 housed the tax office, and after 1927 the province governor's office] the blinds were always rolled down. I remember that, people actually laughed at that, saying the place was always locked up as if it had no owner. The factory [founded by Izrael Poznanski (1833-1900)] kept working, but they lived somewhere abroad. I think part of that family was murdered during the war, but probably not all of them.

The Widzew Manufacture [declared bankrupt in 1933 and nationalized; today a state-owned enterprise] was owned by the Kohn family. In fact, the main shareholder survived the war; he was saved by the Germans [Oskar Kohn left Lodz in December 1939, died 1961 in Argentina]. For big money, what else? Everything's possible if you have money! The Widzew Manufacture was the city's most powerful corporation. They had more money than Scheibler and Grohman, more than Geyer.

The Lodz pharmacy was on Napiórkowskiego Street, which today is called Zarzewska, as it leads from Reymonta Square to the Zarzew neighborhood. There was a chocolate factory there, and the smell of chocolate followed you almost until the next tram stop [a couple of hundred yards].

The pharmacy, founded by my grandfather in the 1900s, was on 27 Napiórkowskiego Street. In the 1930s, there emerged the problem of the storage room being too small, the sanitary regulations became tougher, and the business was moved to 34 Napiórkowskiego Street, at the intersection of Suwalska Street, near Reymonta Square.

By the pharmacy there lived Aunt Klima with her Polish husband, Donat Brzeski, a doctor. In terms of living space, the former pharmacy, at 27 Napiórkowskiego Street, was really crowded. My uncle had a practice there and was receiving patients. The waiting room was the hallway between the apartment, the pharmacy, and the backroom. You had to go through that hallway to get to the backroom, and the entrance to the apartment and the pharmacy was also there. I lived there for some time, soon after coming to Lodz. And I remember that if we returned home late from somewhere, we'd ring the pharmacy bell and enter the apartment through the pharmacy entrance.

There was no sewerage; you went to an outhouse in the open air. I remember the maids taking out the chamber pots. From the pump in the back they brought water, two buckets at a time. And cooking was difficult. I can't imagine today how you can live without running water. The conditions at the Reymonta Square pharmacy were much better, though they didn't have sewerage there either. My father told me that after the nightshift they washed themselves with distilled water. That's bad for health, but that's what they did. And in the backyard, there were such rats! Ugh! Terrible.

Uncle and Aunt Brzeski had no children. They were a good couple. They had a car, which, those days, was a luxury. I remember the trips to Stefanski's [owner of ponds and meadows on the Ner river with a board-renting business and a restaurant], to Ruda Pabianicka for sunbathing. There was a swimming pool there, you could swim. Or you went to Piatkowski's café in Pabianice [town 10 km south of Lodz]. They served the best cake in the area. Aunt died from cancer during the war. She had had one breast amputated even before the war, the tumor metastasized to the other one, and she died. Uncle died suddenly from a heart condition, sometime in the late 1940s. He was a doctor in Lowicz at that time. He was 56.

I remember this episode from my life: Aunt Klima was pretty, but she had very Semitic looks. And I had a classmate, her name was Aurelia Jezierska. She once said to me, 'Listen, I never go to that pharmacy, there's this kike woman there.' I just looked at her really... I saw her once during the war, that Aurelia Jezierska. I stepped into a travel office and she worked there. When I saw her, I ran away as fast as I could, because I remembered that encounter from school. It was very hard for me, to experience such unjustified hatred. I don't know whether it was religious or ethnic... Such attitudes were frequent among Poles. But that's a question of upbringing. The war showed that people reacted differently. I was taken right from the street by my former classmate, of whom I'd have never expected that, and I lived a good few years on her papers.

I lived with the Dirungers. I called them Aunt and Uncle, but in reality they were more distant relatives. Imek [from Joachim] Dirunger was my mother's cousin. The Dirungers were a childless couple. Both were teachers and worked at a private Jewish gymnasium. He was a mathematician, and his wife, Anna, taught Polish literature. She had a PhD from Lwow University, as one of the first PhD students of Professor Juliusz Kleiner [(1886-1957), Polish literature historian. professor at Lwow University]. Anna's maiden name was Lidechower, she was born in Zloczow [until 1939 in Tarnopol province, Poland, now in Ukraine]. Her father was a doctor there, a military doctor, I think. She was roughly of my mother's age, born sometime in the 1890s.

The place was at Nawrot Street, 34, I guess, and that was my official address. We had all, my parents and sisters too, lived there for some time, I think it was 1937. The Dirungers had Art Nouveau furniture, a nicely furnished apartment. They weren't poor, though they weren't rich either.

With Imek we went every Friday night for a walk to the Jewish quarter to watch the Hassidim go to the synagogue. Imek didn't go to synagogue because he was an atheist. There was an Orthodox synagogue at Poludniowa Street. On holidays, especially Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, crowds of people would go there. It was a beautiful world. When I watched those Hassidim going to the synagogue, I felt a whiff of sainthood from them. When I think of human piety, I think of nobleness, of an inability to spite others, to treat them ill. On our way back, we'd buy bagels and bring them home.

I remember Nad Lodka Street well, that was the center of the Old Town. It was another world compared with Piotrkowska, or even Napiórkowskiego Street. I usually went there with Imek. I was afraid to go there alone. He spoke Yiddish fluently. I understand Yiddish but can't speak it. You hardly spotted there a normally dressed person, and if you sporadically did, the Jews said it was a shaygets coming [Yiddish: pejorative for Christian boy]. Many Jews there called Imek a shaygets.

Nad Lodka was lined with stores, usually shoe stores. You could buy cheap shoes there. But those were the kind of shoes that if you went out in them in the rain, they'd fall apart. Something like that happened to me once. I bought myself a pair of very nice shoes. A storm caught me outside, and as I walked in the rain, the shoes suddenly fell apart. And they didn't want to hear about refunding the money. Another thing that I paid 5 or 6 zlotys for those shoes, which was very cheap. The standard price was above 10 zlotys, something like 10-12. But they were so nice!

Nad Lodka was a very poor street. It was also very dirty. They traded in everything there. There were the 'luftgeshafter' there [Yiddish for street vendors; literally 'fresh-air-businessmen']. A man like that called himself a trader, but his whole trade, whole shop, was in front of him: in the box that he carried on his chest, selling shoelaces, buttons, or ribbons. Those were the so-called 'luftgeshafter.' Poor people. And the storekeepers actually chased them away. It was said of such 'luftgeshafter' that they 'lived on tsures' [Yiddish for trouble]. Trouble was what they lived on. That was really terrible poverty. Extreme poverty. It was a pity to look at. And the rats running around. And Lodka itself was a dirty little creek. Often, during a hot summer, it was little more than a swamp.

In Lodz I went to private schools, because there was only one public gymnasium for girls there, the Szczaniecka, on Pomorska Street, and getting into it was virtually impossible. So first I went to Konopczynska- Sobolewska, but I graduated from one named after Cecylia Waszczynska. The former one had been closed down, it ran into some debts and that's why.

From the Konopczynska-Sobolewska school I remember the headmaster, Mrs. Chorazy-Chrupkowa, as I played with her children. They came to us to play, and we went to them to play. I even slept there a few times when it was already war. Mrs. Chorazy-Chrupkowa died in Auschwitz. The whole family was taken. Her husband died too, only the children survived. People said they kept a secret radio transmitter for communications with London [the underground Polish Home Army maintained radio communications with the Polish émigré government in London]. The Germans came, arrested everyone present, and staged a trap there, arresting everyone who'd come.

I didn't particularly like or dislike any of the teachers at the Waszczynska school. I remember that Latin was taught by Mrs. Fischer, who was Jewish, and another Latin teacher was Mr. Zolnierek. Polish literature was taught by Mrs. Gundelach, the sister of the Evangelical bishop from the cathedral church at Wolnosci Square. A typical spinster and typical German. She was a Polish philologist by education. Jodkowna, of the Jodko- Narkiewicz family from Vilnius, taught geography, I think. And gymnastics was taught by Mrs. Weiss.

I remember that on my way back from school I liked to go for a halva or jelly to the Plutos café. I liked the jelly very much. It was made of layers, with each layer being of different color and different flavor. I think they cut it from a larger, multi-flavor piece. One of Plutos's patrons was Julian Tuwim 13. The place was on Piotrkowska, near the Cassino cinema. Then I'd board a tram, or walk back home.

I had friends. I was friends with Hanka Tygier, a furrier's daughter. They had a store selling fur coats at the corner of Legionów and Piotrkowska. She was their only child. I don't know what happened to them. I was also friends with Mala Lastman, whose parents had a large bakery and confectionery at Pomorska. There were three sisters there, Ala, Guta, and Mala. We studied languages, as we were interested to speak at least one or two foreign languages fluently. Besides that we talked, discussed things... We gathered at Mala's, her parents were very hospitable. They always treated us to something, so that no one ever left hungry. But all that fell apart...

During the war, first they were thrown out of their apartment. They moved to the attic, wired it up to the mains, and turned it into an apartment. I remember when they received the summons to report at the ghetto. They were a mixed family and they had hoped they'd be allowed to stay. But they took them. They came very early in the morning and took the whole family. All of them. I think I actually visited them once in the ghetto, but then we lost touch. We had to because I left Lodz.

For the summer vacations I often went to Spala [small town 50 km east of Lodz]. It's near Lodz, you went by bus. The bus service was privately- operated those days. There were Polish bus operators, and there were Jewish ones, so you had two buses a day 'hin und zurück' [German for there and back]. A nice place, beautiful forests. There was a little palace there where Moscicki [Ignacy Moscicki (1867-1949): president of Poland from 1926- 1939] used to come. I remember Mrs. Moscicka riding around on a horse. She was always escorted by cavalrymen, the 'uhlans' [traditional Polish cavalry formation, equipped with lances, sabers, and pistols]. The popular notion was that they were 'beautiful as dolls,' and they were indeed handsome, and were great horse riders. And those uniforms with the blue stripes, 'himmelblau' [German for 'skies-blue'].

So I went to Spala for those summer stays. Mrs. Dirunger also organized such stays several times, taking high school students for the summer. I think I was with her once. There was also a gymnastics teacher at my gymnasium, her name was Ms. Weiss. She also organized the summer stays for students, and I was once with her too. One summer, I remember, I was in Spala twice, for two weeks each time. We also went to Rogi [now a Lodz suburb]. My parents were friends with a Polish family, the Lachmanowiczs. He was a public notary, had a practice at Pomorska. And they had that property, a small estate near Lodz, called Rogi. They had a very nice little house there.

My parents came to Lodz about a year and a half before the war. Przedecz and the whole area were turbulent. The area was swarming with refugees, as the Germans were expelling Polish-born Jews, and all that human mass was going through Zbaszyn [ca. 70 km west of Poznan and 200 km of Przedecz]. The Germans took them to Zbaszyn 14 and told them to go whence they had come. That was 1937, I think. So the whole border area became a very unpleasant place. Life was uncertain, there were robberies, all kinds of things were happening.

My father ran a pharmacy there for a long time. Then he sold it and moved to Lodz. He bought a stake in a pharmacy at Napiorkowskiego Street. There were three or four partners there. My parents had trouble getting their ends meet. Well, things weren't going too well. I have a photo from that time with flowers in my hair, taken in Tyraspolski's studio, soon after the war broke out or shortly before. Tyraspolski's was a good photo studio on Piotrkowska. I had several pictures taken there, and this is the only one that survived.

The pharmacy no longer exists. Everything's been thrown out on the street, shattered... Everything's shattered. In fact, what use is there in going back to all that? None. Ah! No use talking about it. It'll never come back. My mother died like a beggar, and it wasn't much better for my father. You only wonder sometimes what crimes people committed to be punished like that? They were decent folks, cared for their families... and they had to die. That's vile. They shot them, and still had to give them a kick if that weren't enough. Life's terrible. I've been watching life and I'm fed up with it.

When the war broke out, the Germans didn't take Jews to the ghetto right away, but immediately started confiscating everything, whatever anyone had [the Lodz ghetto was set up in February 1940]. If you were a non-Aryan, they immediately nationalized your property. They had organized the so- called 'Kriegswanderung' [German for 'wartime wandering'] and had to give some employment to those people. So factories and all the better businesses were being given in the first place to the Kurland Germans [ethnic Germans living before WWII in Kurland, roughly the southern part of present-day Latvia; following the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact of 1939 which 'restored' Latvia and Estonia to Soviet control, evacuated and resettled in various parts of occupied Poland]. Especially if they had left some assets in their home country. Very many of them came to Lodz.

I went to the General Government 15. Not alone, with my parents. Some of our relatives went to Czechoslovakia. They wandered around, you know, a bit here, a bit there. We all spoke German well, there was only the question of getting a permanent address and a fake ID, but that was still relatively easy at the time. Later it became more difficult and cost more.

I often wondered what had happened to the Dirungers. I searched for them after the war. I know they had the 'Jüdische Wohngebiet'... [German for Jewish residence area, euphemism for ghetto]. A summons to relocate to the ghetto. They didn't know what to do and went to live there. And there they died. They died in the early period, there must have been a reason. There was an 'Unterwelt' [German for underworld] there - thieves, prostitutes, and so on, and, in the ghetto reality, those people dominated. It was a regression to primitivism. It seems to me the Lodz ghetto actually led the way in that primitivism, that humiliation of people. The atmosphere was rather peculiar.

The president of the Lodz Judenrat 16 was this very simple man, Rumkowski 17. My daughter has this saying: 'simpler than a piece of stick.' And he was precisely that. A small storekeeper, simpler than a piece of stick. But the Germans hoisted him up, even though they had other, better ones, they chose him.

The ghetto had its own currency. It was valid only in the ghetto. I don't know whether it was the 'Ghettoverwaltung' [German for ghetto administration] or the Germans who were printing the notes. [Editor's note: The bills, bearing Rumkowski's signature and consequently referred to as the 'rumeks,' were introduced in 1940]. The separate currency was also a form of humiliation. The point was to prevent you from giving bribes or buying anything apart from that which was for sale in the ghetto. But bribery still existed. The ghetto was an opportunity to get rich. As the saying goes: 'Gelegenheit macht den Dieb.' [German for 'opportunity makes the thief']

I was in the ghetto for only a very short time, perhaps three weeks. [Editor's note: Mrs. Fiszgrund refused to talk about her family's experiences during the war. The issue remains too painful for her. She was in the Lodz ghetto with her mother and her sister Irena]. It was at the end of 1942, the period of great terror. Irena, my younger sister, born in 1923 or 1924, worked in a pharmacy in the ghetto. One day she left the ghetto and never returned. She had the so-called Aryan papers.

I walked out too. I remember I was walking down the street and crying, my nerves cracked, simple as that. And someone accosted me, 'Alina, Ala, why are you crying? What's happening? Are you alright?' It was my friend, we went to gymnasium together, and when I told her everything, she said, 'Don't worry about anything. You'll be on my papers. I'll report them as lost, and you take them and go to Vienna, and that's it. I'll give you an address whom to go to, they'll hide you, and everything will be okay.'

It was like fantasy, like a dream. And I said okay and went with her. I got an Austrian ID from her. I speak German fluently. With a strange accent, but I can say everything, and that's a big advantage. To this day I have her name written in my Polish ID as my maiden name: Gruszczynska. But I don't think she'd want me to talk about her. She is a Viennese lady with whom I still keep in touch. An old lady, she's 88 now.

I left for Vienna during the Germans' great march eastwards, in Russia. They stood at Stalingrad's gates 18 and still believed they'd win the war. I remember the banners at railway stations: 'Räder müssen rollen für den Sieg' [German for 'Wheels must roll for victory']. You saw that everywhere, in Austria too.

In Vienna, Jews lived in the 2nd Bezirk [German for district]. A place where I was only for a short time and could encounter them. During that period, Jews weren't allowed to go out after 10am. The 2nd Bezirk was the only area where they were allowed in public. They weren't allowed to walk the sidewalks, had to walk in the middle of the street. And they had the star. [Editor's note: When in public, Jews had to wear a badge with the Star of David.] But at least you could survive somehow there.

Many people helped me in Austria. I'll actually say the Vienna times were good times. The only thing is I felt very alone, even though I had friends there too. There was this artist, a singer, Milica Kordius. It was a stage name, her real name was different. She performed mainly in England, also in America, because she loved to sing in English. She lived in Vienna, but she was Serbian, from Sarajevo, I think. I met her during the war, and received a lot of good from her. She even helped me financially from time to time. I was close friends with her until her death. She was a pretty and wise woman. A woman of great heart.

Besides that, sometimes someone felt sympathy for me, and, for instance, gave me some money. There was a lady, for instance, who gave me a certain sum of money so that, if I needed something, I wouldn't have to urgently look for a job. Getting a job wasn't a problem, but not all jobs were safe.

I lived on Burggasse, near the Volkstheater, with Mrs. Hanzie Leinauer. She was a violin player, a music teacher. It was a very liberal and interesting family. My host had a sister who married a Jew. That sister lived with her kid in Vienna. The boy was seven or eight years old, and under the law of the time, he wasn't allowed to go to school. He was afraid to go out on his own. And his father was in hiding in a small town in the south of the country. His wife sometimes went there, though that wasn't simple.

I left Vienna when the Russian troops were already approaching. It was fall 1944, a time when Lithuania and the small Baltic states had already been taken by the Russians. The Lithuanians and Latvians were fleeing to Switzerland. I wanted to get to Switzerland with them. They were fleeing to Montreaux, to a refugee camp. But you couldn't say there you were Jewish, all other ethnicities the Swiss were accepting without saying a word. So I gathered some money and went towards Innsbruck. I had a friend there with whom I could stay for a couple of days.

You met all kinds of strange people those days. People were fleeing from camps, from prisons. You boarded a train but you didn't get far because a shelling would start right away, and the train would stop in a field somewhere. They'd order everyone out and drive you to those 'Schützengräben' [German for trenches]. Those were the kind of protective digout holes. I got as far as Innsbruck and there decided to call it quits.

When I returned to Vienna, the house wasn't there, nothing was there. It had been destroyed during one of the air raids. Hanzie Leinauer died in the basement of that house. Her sister with her son were in the country then, fate wanted it that she had gone to visit their husband. All three survived the war. When I returned to Vienna, I didn't know what to do. I remember I wanted to get the 'Durchlassschein' [German for travel pass] that's how it was called, to go to the former Polish territories, now part of the Reich. But when I went to apply for it, they told me, 'Why do you go there? The front from the Vistula is moving fast and it's very dangerous there at the moment.'

I returned after the war. Why did I return? I simply didn't imagine how things were. You can say 'distant fields are always greener.' Vienna wasn't any paradise during the war, life was hard there. There were very many foreigners there, and besides, the city was ruined. So it was survival of the fittest too. But there was also the kindness, the politeness, even after the war, the early period. Another world, simply. And when I came to Poland, it was clear most people had experienced social advancement. I thought I'd be returning to something that my parents owned, but I returned to nothing... I didn't affiliate myself with any nation, it was basically all the same time whether I was here or I was there.

I returned to Poland with my first husband. His name was Mieczyslaw Golebiowski, I met him on the road, in the West. He was from Warsaw, I don't know his birth date. It was an unsuccessful marriage. That's life, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. We came to Cracow with one of the first transports. In 1946, or perhaps late 1945. A friend gave me the address of her relatives in Cracow. That's why I came here.

Finding a job was impossible, it was macabre. Life was hard, and I hardly knew anyone. The locals, they had some connections perhaps, but I had no family here whatsoever. I was looking for a job through those people that my friend had put me in contact with. And they not only didn't help me but also sold out my wardrobe for nothing. Because I came to Cracow with a suitcase or two of clothes.

In the end, I went to the repatriation office [organizing the settlement of Poles in the formerly German 'regained territories' to the west and north, granted to Poland in return for its lost eastern territories], and they gave me an allocation for Nysa [south-western Poland, near border with Czech Republic]. But instead of Nysa, I went to Lebork. It's a town in Pomerania [northern Poland]. My husband was a dental surgeon, and had been allocated a post-German dentist's office in Lebork. My daughter, Wanda, was born in Cracow in 1948. Then I left for Lebork to join my husband.

My husband was making quite good money there, but I didn't want to stay there. Lebork was in ruins. A cemetery ran through the center of the city, on both sides of the street. I was afraid to go out after dark. To make matters worse, my husband fell ill. And we left Lebork after about a year. We returned to Cracow, but finding lodgings was difficult. At first we lived in a hotel. Then we moved in with my husband's family. Jewish organizations 19 were helping us a lot, that's true, but you couldn't always count on that. And living of charity is a very unpleasant experience.

Then we moved to 22 Batorego Street, which was downtown, to an apartment we shared with the Millers. Mrs. Miller, nee Lebers, was Jewish. She had converted to Catholicism to marry Antoni Miller, a Pole, who saved her. He was the director of Bank Zachodni in Cracow before the war. Mrs. Miller lost her first husband and her son during the war. I don't know what their names were. The boy was in a post office, sending a letter or something, when he was spotted by his [former] nanny. I don't remember her name. And she denounced him as being a Jew. I remember I told Mrs. Miller to report that. But I guess she didn't. I don't know why.

My sister, Irena Birnbaum, married name Warlicka, died in 1951. She was a pretty woman. Taller than me, good-looking. After the war, she went to Israel [then Palestine]. It was 1946, perhaps 1947. She didn't stay there for long, because she didn't like the place. On her way back to Europe, on a ship, she caught the flu. There was a flu epidemic a couple of years after the war, in 1947 or 1948. She had the back luck to catch it. She returned to Poland seriously ill. She developed cirrhosis of the liver and three years later died. I don't know whether it was because of the flu or because of penicillin overdose, as that was suggested too. It was the early period of penicillin use.

After returning to Poland Irena lived in Wroclaw. She was married for a short time, two years perhaps. She had a female friend who was a doctor and who died while giving birth. To her second child. Irena married the father of those children, but she was already very ill by then. She had bad luck, died before the age of 30.

I am very reluctant to go back to those post-war days. Very, very reluctant. As soon as I could, I hired a nanny for the child and went to work. First I worked as a bookkeeper for Bank Narodowy on Basztowa Street. That was close to home, but they paid poorly. Then I worked for a winemaking enterprise. I quit soon because it was far from home.

I divorced my husband and was left alone with my child. I have the pre-war high school diploma, so I started studying, first pharmaceutics, then law, but I completed neither. I was very nervous, unable to concentrate. Besides, I had no money, was unable to reconcile work and study... I simply couldn't manage on my own.

During that time I met Maksymilian Fiszgrund. He had just lost his wife, and was alone, I guess, when I met him. It was his second wife, nee Keller, I think, and her first married name was Fedbelt. She had this strange first name... Hermina! It was a very short-lived marriage. In 1950 she developed a suppurative inflammation of the gall bladder, infection set in following surgery, and she died. There was a Jewish club on Slawkowska Street, and there I met Fiszgrund [Editor's note: Mrs. Fiszgrund calls her second husband by his surname]. This may have been 1950. In 1951, in the fall, I married him. In October.

We lived on Lea Street [then Dzierzynskiego]. I lived there for 40 years and today my daughter lives there. I got a job at an institution called Zjednoczenie Kotlarskie, later renamed Centralne Biuro Urzadzen. I worked there for 22 years. First I worked as the director's secretary, then in the planning department, and after that in one of the technological departments. In the end I worked in the experimental laboratory, and that's the period I have the fondest memories of. Later I fell ill and was granted a disability pension until retirement.

Then I started working for the TSKZ 20. Fiszgrund held a full-time position at the Jewish Committee, he was the head of the assistance department, I think. He also held a position at the TSKZ, the deputy head of some department. After the Jewish Committee was dissolved in 1953 or 1954, he was granted first a disability and then a retirement pension. He started doing translations. From German into Yiddish. He was also a correspondent for the Folksztyme 21, writing about the activity of Jewish organizations in Cracow. Later I also did it for some time.

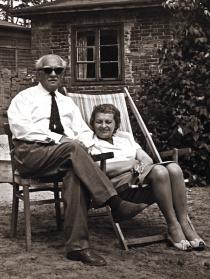

My husband was a very decent man. Calm, quiet. Very calm. He was unable to get mad, and that's a precious thing. I can't do that, I'm very emotional, I'm different. We never quarreled, even though there was a substantial age difference between us, thirty years. My husband died in 1978. He is buried in the Jewish cemetery at Miodowa.

My husband's father, Szymon Fiszgrund, acted as rabbi in Sulkowice [town 25 km south of Cracow]. Sulkowice is a small town near Cracow, beyond Myslenice. The rabbinate was in Myslenice [10 km from Sulkowice], and Szymon Fiszgrund was the shochet there. The shochet's role, for instance, is to intone the Kaddish during a funeral. He also weds people, and has other duties too. [Editor's note: those are the duties of the chazzan, nevertheless in some poor communities the same person could have been shochet, mohel and chazzan.] My husband was a child from his father's first marriage, his mother, Bronislawa, died delivering another baby, and the baby died too.

My husband had a brother, Salo 22, six years younger than himself, and a sister. The only thing I know about the sister is that she married a man from Bedzin [town 12 km from Katowice] and during the war was taken with her husband and child by the first transport from Bedzin to Auschwitz [in May 1942].

Wait, they had one more brother. He was much older than them. I don't remember his name. He had a stationery store on Stradom Street [in Cracow] and had grown-up children. A son and a daughter, if I remember well. His son, Szewoh Fiszgrund, went to Antwerp to learn diamond cutting. When the Germans entered France, he fled from Antwerp to London, and spent some time there. He married an English-born Jewish lady. Later he lived in Johannesburg [South Africa]. I don't know whether he got there during the war or afterwards. He was an elegant gentleman, and a very rich one too. It seems to me that the business he established in London is still in operation, and that it is run by his son.

Anyway, Salo Fiszgrund, my husband's other brother, broke free from Sulkowice thanks, I think, to a guy named Aleksandrowicz who had a stationery wholesale business in Cracow. Salo got his first job there as a bookkeeper. Shortly before the war [WWII] he held a directorial position at some bank, I think. During all that time he was also active in the Bund 23. He had two children with his first wife, Julek and Hanka. Both were born in Cracow. Julek was one year an a half younger than me, so he must have been born in 1923. Hanka was one and a half or two years younger than Julek, so that's birth year 1925. I don't remember the name of Salo's first wife. She was from Cracow, that I know for sure.

Szymon Fiszgrund had two more children with another woman but they had never undergone the wedding ritual. I don't know what her name was, but the children bore her maiden name: Israeler. Such situations were common in Jewish families. The ritual wedding had to be registered in the official books. At every community, or at every registrar's office, separate books were kept for people of Mosaic faith. They were usually kept by a Jew who could read and write.

Sulkowice was part of Austria-Hungary then, and the official had to know German, Yiddish, and the two alphabets. On top of that, he had to know all the regulations. That was costly. That's why the Jewish books are full of stories like someone was widowed and the rabbi simply blessed [the second marriage] on the spot, a bit, so to say, the Catholic way. He made it possible for them to live together, but he couldn't officially wed them, because that would mean costs in the office. So the other woman ran away from Szymon Fiszgrund because she found herself another man.

My husband's stepbrother, Aron Abraham Israeler, was 12 or 13 when his mother ran away from home. Soon after that his father sent him to Berlin, to some relatives. That was between 1905 and 1910, and my husband went to Berlin during roughly the same time. Aron grew up with those relatives, and eventually married a Jewess in Berlin. Her name was Rywka, Rywka Israeler. In 1934 or 1935 they were expelled from Berlin. They could have deported them to Poland, because he was Polish-born, but Rywka was a very smart lady, a street-smart one. And she secured a permit from the British for them to settle in Palestine. They lived in Haifa, had a son. Aron worked in the post office. He wrote us letters. He died in the early 1960s, and his wife outlived my husband, died sometime in the late 1970s.

Hanka Israeler, Aron's sister and my husband's stepsister, stayed in Sulkowice. She ran her father's house. She was murdered soon after the war broke out. She probably didn't see anything of the world beyond Sulkowice in her entire life.

My husband was born in 1887 in Sulkowice and went to elementary school there. Later he was taken care of by Wilhelm Feldman [(1868-1919): writer, literature historian], who saw to his education. The two were related somehow, but it was a very distant relation. Feldman wrote the book 'The Sorceress' [Editor's note: The interviewee is probably referring to the drama play 'The Wonderworker'], which my husband translated into Yiddish. And he took care of my husband. He sent him to gymnasium, my husband eventually passed the high school finals, on an extramural basis, I guess. With the high school diploma he went to Berlin. He spent a year there and completed the 'Welthandelsschule' [German for school of global commerce], as that's how long it took those days. That was before World War I.

Then he returned to Cracow and started working as a reporter for Naprzod ['Forward', first Polish socialist daily, 1892-1939], the official newspaper of the PPS 24. Those days there were no degrees in journalism, the reporters usually only had high school education. Here, in my husband's journalist ID, you can see the signature of that well-known Naprzod editor- in-chief, Haecker [Emil Haecker, born Samuel Haker (1875-1934): PPS activist, literary expert and outstanding theatre critic]. Naprzod was a left-wing newspaper, but, you know, there were various orientations.

Fiszgrund got married the first time in Sulkowice. His wife, Janina, nee Kunstlinger, was two years younger than him. She was born in Sulkowice. She ran the house and looked after the children. They lived in Cracow on Lubicz Street. I have a photo of hers, taken, I think, in that apartment on Lubicz. They had two daughters: Rozia [from Roza] was the older one, and Bronia the younger one. Rozia was two years younger than me, which means she was born in 1923. I don't know the age difference between them, I think it was two years. I have a photo of my husband with his daughters on a street in Sulkowice.

When the war broke out, my husband fled to Russia. The entire Naprzod editorial team was later arrested and sent to Auschwitz. Cyrankiewicz 25, who was also one the Naprzod editors, was in Auschwitz too. My husband didn't manage to take his family with him, it was impossible for him to flee with them. Crossing the San wasn't a simple thing to do [San: river in south-eastern Poland; from 1939-1941 San was the border river between the part of Poland occupied by Germany and the USSR]. It is a swift, deep river. And there [in Russia], my husband knew Wanda Wasilewska 26, who later went by the married name of Korniejczukowa and she promised him she would help him bring his family to Russia. That never happened because in the meantime war broke out between Germany and Russia 27. He lost touch with Korniejczukowa. The plan was unrealistic also because, when Wasilewska was making her promise, my husband's family had already been deported from Sulkowice.

I know that first the females [Maksymilian Fiszgrund's wife and daughters] were taken, together with my husband's father, to Myslenice. There was a sort of processing ghetto in Myslenice [1200 people]. From Myslenice they were taken to Skawina [town 10 km from Cracow], and from there people were transported in batches to Belzec 28. But documents that my husband had, said they had all been shot in Skawina, the whole batch. 'Unerhört!' [German for unheard of], horrible. Wars are horrible as such, but that war, with its idea of annihilating people solely because they were born in the wrong bed, is something that is beyond comprehension.

Fiszgrund spent the first two years of the war in Buczacz [ca. 140 km south- east of Lwow, presently Ukraine], working for the Jewish community there. But then the [German-Russian] war broke out and the Germans arrested him after entering Buczacz. My husband was in touch with someone from the PPS in Cracow, and he was extracted from jail by some PPS activist, I don't remember his name. The man handed him over to another man who brought him to Cracow and handed him over to Bobrowski [Czeslaw Bobrowski (1904-1996): renowned economist, PPS activist]. They had some problems on the way, there were pass controls on the trains after all.

Salo Fiszgrund made it to the other side of the [USSR] border and thought that, as a Bund member, he'd be welcome there. But the communists didn't like the Bund. It's the truth. The Bolsheviks 29 were afraid of the international masonry and believe that it had its roots in the Bund. Salo crossed the border with a group of people. The Russians arrested them and took them to Minsk [until 1939 in the Belarussian Soviet Republic, presently capital of Belarus]. From that group two persons were sent to the Siberia, and the rest found themselves in jail.

Salo was put into jail, in Minsk, for half a year, or a year, I don't know. And there they exchanged him. The Russians released him to the Germans as a Pole, and the Germans released someone to the Russians. I know they exchanged him, and because he was circumcised, the Germans sent him to the ghetto. I know for sure that two or three people went to the Warsaw ghetto 30 for being Jews. Some well-known Jew was replaced together with Salo. I don't know whether it wasn't Feiner 31. That must have been late 1940 or early 1941, certainly that. Salo made it out of the ghetto through the sewers but he was still in Warsaw. The Zegota 32 equipped him with a fake ID in the Polish name of Henryk Osiecki.

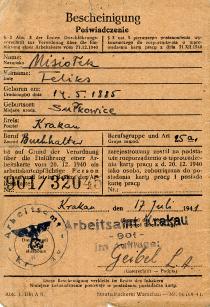

My husband got through to Cracow and there received [fake] papers in the name of Feliks Misiolek, those papers were from the Zegota too. He went to Wieliczka [small town 10 km from Cracow, famous for its historical salt mine] and took up residence in Lednica [a Wieliczka neighborhood], a residential area where those salt mine workers lived, with a guy named Leon Palonka. Palonka was a member of the Bataliony Chlopskie 33. A decent man, very decent. A PPS member, very ideological, highly devoted to the party. I knew him, he died of cancer. My husband stayed in Lednica until the end of the war.

From the moment of returning to Poland, my husband was provided for by the Joint 34. There was that Mrs. Hochberg-Marianska [Maria Hochberg- Marianska, courier for the Zegota's Cracow branch; emigrated to Israel after the war]. She used a Polish ID in the name of Marianska, but her real name was Hochberg. She brought money to Leon Palonka for the people he kept in hiding.

My husband and Salo were writing to each other. They never lost touch. It's Salo in this one photo I have [dedicated: 'To my Dear Cousin, Zygmunt. Vamosmicola, April 1942, Magyarorseg']. I think it was taken after he had made it from the ghetto to the Aryan side. His fake name was Henryk Osiecki, not Zygmunt, but they wrote to each other under assumed names to avoid identification. You know, when my husband looked at the photo, he knew it was Salo. It may have been sent by mail, or through Hochberg- Marianska [who, among other things, helped ghetto runaways transfer to Hungary]. She saw both, after all. Salo was also in touch with someone else from the Joint. I don't know who it was. Hochberg-Marianska was too - she was getting the money from somebody. She wrote a book after the war and there she mentions my husband. She's dead now, she was older than me.

Salo Fiszgrund got married again after the war. His first wife, the mother of those kids, Julek and Hanka, died in Piotrków Trybunalski. There was a ghetto there. It was really 'ein Vernichtungsghetto' [German for 'an extermination ghetto'], people were sent there to be exterminated. Julek was with his mother, but only until some point. He later found himself in Skarzysko-Kamienna [town 135 km north-east of Cracow], something I know because Reiner, a friend, worked with him handling TNT or picric acid in the camp there 35.

Hanka was saved by Anielcia, Salo Fiszgrund's housekeeper before the war. What her name was, I don't remember. She's dead now. I know she had one son who was a farmer, quite a prosperous one. Anielcia took Hanka to the country and registered her there, saying she was her illegitimate daughter. And Hanka got papers to that effect. She never talked about that, but Anielcia loved to tell the story. It seems to me she also said Julek visited them there once or twice, but him she was afraid to keep. After the war Anielcia kept working as housekeeper for Salo Fiszgrund, and Hanka called her 'mama.'

As for Maria-Gusta, Salo's second wife, Anielcia was against her, didn't like her. Emigrating to Israel, Hanka took Anielcia with her. Anielcia was one of the first persons in the world to be awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal 36.

Salo's second wife, Gusta-Maria, was older than me, birth year 1917 or 1918. Her proper name was Guta. Maria was her name from the fake Aryan papers. My husband called her Gusta-Maria. I know that her first husband was a jeweler and had a store, probably on Targowa Street. He died in the Warsaw ghetto. She met Salo in the ghetto, being already a widow. They left the ghetto together through the sewers. She went to some priest, somewhere near Warsaw, I think it was Podkowa Lesna [small town 20 km south of Warsaw], and she worked as his housekeeper. She was a pretty woman, good- looking, shapely. She worked as a clerk after the war.

At first they lived at the Jewish Committee where Salo worked. The first Committee, which was established in Warsaw, had its premises in the Praga district, on Targowa, it was a detached house surrounded by a garden. I think it's this house in the photo I have here. I guess it's 1946 or early 1947. Salo was the head of the assistance department. After the Jewish Committees had been wound up, he moved to the TSKZ.

Salo Fiszgrund was the last secretary general of the Bund. He was the secretary general when the PPS, the PPR, and the Bund merged 37. I think he signed the unification act. Some Bund members held it against him. I guess it was the only solution, but I'm aware that some Bundists were against it. I don't know whether there is any secretary general now [the Bund disbanded itself in 1949], but Marek Edelman 38 is perceived as one in Poland today.

Salo was for some time the Joint's official representative in Poland. He frequently traveled abroad on Bund and Joint business. He went to Switzerland and, I think, to France. The support, the dollars, that the Joint was sending was, I think, at first $20 [per person], then $25, and then $40. I know this well because I later worked with it, in Cracow. You didn't get that once a month. At best, it was six times a year, if you had the lowest state pension. But those were only sporadic cases for someone to get it six times a year. Most people got it once in a quarter. Some, only twice a year.