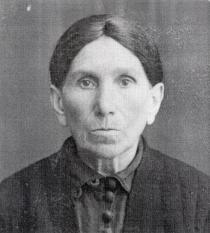

Bella Bogdanova

Riga

Latvia

Interviewer: Svetlana Kovalchuk

Date of interview: August 2001

My family and young years

I have tried to pass to my daughter, all the grace and benevolence I gained from my family circle before I was fifteen. I lost everything, all my family in 1941. Fifteen years of happiness ended abruptly. First my father was shot on 24th July 1941; then my mother, brothers, Granny and other close relatives were murdered on the Chanukkah holiday, 13th December 1941. My husband was the last one I kept with me. The Lord took him away 19 years ago. He died suddenly in my arms. I became orphaned around the age of 15 – I lived 15 years with my parents, and I lived 34 years with my spouse.

My mother, Bertha Blumberg [nee Brenner] was born on 8th August 1899. She had a sister, Paula Brenner, born in 1901 and a brother, Shaya Brenner. All of them were born in Kuldiga [155 km west of Riga]. Probably my mother went to school at the Kuldiga Gymnasium [the city was called Goldingen until 1920]. Her parents died early so she went with some relatives over to Liepaja [port city, 215 km west of Riga]. A lot of the Brenners lived in Liepaja. Uncle Shaya stayed in Kuldiga till 1940, but Aunt Paula lived together with us. She had a personal tragedy and remained unmarried – so she lived together with us. I know very little about my mother’s family. I know practically no dates. The only thing I can say for sure is that the Brenner clan was very large. It was something different with my father’s relatives.

I have more information about my father’s relatives. This is thanks to the fact that my Granny, my father’s mother, lived a long life. My father’s name was Hasl Blumberg. He was born on 5th January 1901. He learned watch-making from a watchmaker. This was arranged in accordance with the tradition that sons were apprenticed to craftsmen. He had a brother named Meier, born in 1899. He was a drover like their father. My father looked like my grandfather, but Meier looked like Granny. They were very different people deep down and in the way they carried themselves, too.

Our other Aunt Paula was my father’s sister. Paula went to Canada, married somebody from Liepaja and had three children. She came back to Latvia in 1924 or 1925. They lived with our granny. Later her husband took two children away to Canada, but the youngest, Genya, stayed with her mother. She survived the Holocaust. She was liberated by the British and then she went to her father in Canada. But Aunt Paula remarried in Lithuania. She was pregnant when the Germans put her in the camp. They cut open her stomach while she was pregnant.

My grandfather’s name was Leibe. He was born in Grobini [small town in today’s Latvia] in 1864. My granny – his wife – was from Pikeli, Lithuania [a small city called Pikeliai in Lithuanian, Pikeln in Yiddish, located in the North of Lithuania bordering with Latvia]. Her family name was Strol. I think she was born in 1864. I know nothing about her marriage. They lived in Grobini at the very beginning, but later they moved to Liepaja. That was because there was a tendency for Jews to move from small Lithuanian cities to Courland. [Courland is the historic designation of the left bank of the river Daugava, in today’s Latvia, where Jews coming from Germany used to dwell.] Maybe my granny got there in this way.

Granny didn’t speak German, so we spoke to her in German, but she answered in Yiddish. Yiddish was the language in which they communicated. She understood us well and gave us 20 centimes for visiting her. I loved my granddad so much! He had horses and a cart. In winter, when the snow was deep, he took us around Liepaja on a sledge, with a horse, which had bells on. Jews in our family were invariably well off.

Granddad died in 1935, while Granny was killed on Chanukkah on 13th December 1941. My granddad was the only one amongst my kin who died in a human manner. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find his tomb in Liepaja. After Granddad’s death we visited Granny each Saturday. My father always gave her money, but his brother Meier begrudged this.

My granny was an orthodox Jew and very religious. She wore a wig and prayed. Granddad and Granny lived separately. Granddad visited the bes medresh every day, which was situated near a big, beautiful synagogue. Before going to the bes medresh he put on his tefillin. Granddad was very religious, but my father was different. We had an ordinary Jewish home. Granddad and Granny didn’t try to make us orthodox. Sabbath was still Sabbath, of course. Daddy visited the synagogue with us on the holidays. Every holiday was celebrated. The rituals were observed as well. We kept kosher and had special dishes for dairy food and for meat.

When Pesach came, my mother took out silver dishes and the best golden one. On the first and second seder we stayed at home. On the second day our relatives came, and all of my cousins would be there. The children ran around, we made a lot of noise and jumped around. It fitted the holiday. Our house was a very hospitable one. My mother cooked a lot of special, sweet Jewish dishes such as kneydlakh, boiled with honey and almonds. The adults sat in the lounge, but we were in the dining room. When it was time for dinner, everybody gathered in there at the big dining table.

My mother fed a lot of people at that table; there were relatives and assistants of my father, too. My father often worked at home. There were six of us in our family: Mother, Daddy, Aunt Paula and three children. My father earned money enough to keep a family of six people. He kept a lodging-house of five rooms with full utilities. We lived on the first floor of a two-storey building.

I loved my father very much, my mother, too. But Daddy would always help anyone who needed it. He was a watchmaker. There was a clock production enterprise in Liepaja, which belonged to Ruseniek. He bought components – the small machinery needed for clocks – in Switzerland and then my father and his team assembled clocks. Watches were especially popular. There were two names on the clock-faces; the first was the Swiss company and the second was Ruseniek. He was a Jew, a rich one. He had two houses. My father was well known in Liepaja, he was a man of stature and very popular. As a rule, Daddy came home at 6 o’clock; when he was late I became nervous and it shook me. ‘Where have you been?’ I would ask him. But he would just hug and kiss me.

My mother always took out library books in German. She bought children’s books for me in German; we had a lot of them. I loved to read books on Saturdays until 11-12am, because we had a routine: first breakfast at 8am, second breakfast at 11am, lunch between 1 and 2pm, tea-time at 5pm and dinner at 8pm. We were fed well. Maybe it was thanks to this that I survived. My body was well nourished. We had drinking-chocolate and bread and butter with salmon or sausage for the first breakfast. Chocolate every morning! Also, at 7am two liters of milk would arrive at the front door. We had scrambled eggs, poultry, vegetable salad, coffee and milk for second breakfast. Lunch was just lunch.

I didn’t like the taste of mushy porridge oats or drinking a cup of sweet cream. I was thin and pasty-faced. So my mother paid me 20 centimes for drinking it. I had a piggybank and it helped me save money. When Mother’s Day came in May, my little brother and I bought daffodils for Mother with that money. He had no savings because he ate everything and was never paid.

I remember my mother’s evening dresses for going to parties with my father. One of her gowns was a full-length, deep-cut, black dress with a big white rose. Another evening dress was full-length and lacy. When they were going to parties, my father told the yard keeper in advance that they had to go and a car would be summoned. Can you imagine? I saw so much beauty and grace during the first 15 years of my life!

What mischief we got up to, Abrasha [Abraham Greinom] and myself, when our mother and father left us alone! I was closer to him than to my youngest brother. I was born in 1926, and Abrasha was three years younger; he was born in 1929. The difference between my youngest brother and me was nine years. Hirsh Isaac – we called him Harry at home – was born in 1935. I made up both my brother and myself, including lipstick. We used my mother’s perfume, too. I put Mother’s high-heel shoes on! We went through everything! We had a large salon with a big mirror. So we’d stand in front of the mirror arm in arm. I’d say to him, ‘We are beautiful, aren’t we, Abrashenka?’ And he always said, ‘Yes.’

We had no servants, but a woman came on Fridays to help clean our apartments. Of course, Aunt Paula lived with us, so she helped a lot. In those days in Liepaja, the streets were washed both in the mornings and evenings. Nobody took their street shoes off in the house; we weren’t used to slippers. The yard keeper was the right-hand man of the landlord. It was a Jewish house we lived in; we took up the first floor. The city of Liepaja was mainly Jewish. About 90 percent of the houses belonged to Jews, plus all of the shops and banks.

For the laundry there was another special woman, who washed linen for a whole week once every three months. She washed it in a huge boiler in the yard. Mother paid her well, provided for her and gave her some food, too. We lived well; we had enough linen – more than six pillowcases and six sheets.

I was a pampered girl when I was young! I used to do nothing at home. A woman was hired and used to come each Friday, on the eve of Sabbath. She cleaned everything, polished the floors. My mother did some light cleaning every day with a small rag. If Mother sent me to the kitchen, to check on the boiling kettle, I would cry loudly, ‘Mommy, it hisses and steams!’ I was pampered too much. I was their only daughter, so I was my father’s best beloved.

I attended the best private kindergarten in Liepaja and afterwards, the best elementary school. Doctor Hyte was the headmaster of these institutions. I don’t remember his first name. My brother Abrashenka attended a school where they taught only in Hebrew. After Ulmanis 1 became the ruler, Yiddish was used as a teaching language. Daddy sent me to the best school to make the best person of me I could be. German was the language of instruction there. I had private English lessons for two years.

Our school didn’t have a religious denomination. We had two lessons per week on religious history and two on Bible studies. Religious subjects would be taught in Hebrew, of course. And I got straight A’s, naturally. My father spoke Hebrew well. He translated everything for me and helped me; I forgot everything, because I could be rather empty-headed. Our school was shut on Jewish holidays. We liked our homeroom teacher, Hanna Hermer, very much. She was very nice, but she died at an early age.

I finished only seven grades of school, but the level of education was very high there. It could be compared to eight or ten years at a Soviet school. That was my whole education. Maybe I would have become something worthwhile if the war hadn’t happened. I had a good girlfriend. We went to one another’s birthday parties. Beautiful birthday parties used to be arranged in those days.

I had a room for myself, and my brother Abrasha had his own, too. We only had five rooms, but we needed six, so my father could work at home in peace. He had to work in my brother’s bedroom. He divided the room in order not to trouble my brother. My mother and father had only love and very few material possessions in the beginning, but as time passed they became quite well off. One time my father was working behind the room divider while Mother was sitting and patching our socks. She said to him, ‘Let’s sell everything and go to America.’ Father replied, ‘What do you mean! We have such a nice living here. We have everything we need. How could we give it all away and go abroad?’ Mother regularly tried to budge him; maybe she had a premonition. I was a real Daddy’s girl and never liked the idea of flying away.

We lived so well; what our parents gave to all three of us, I wasn’t able to give to my only daughter. I remember my father drawing a salary every Friday. He bought us fruits all year round. I even tasted chocolate candies. I was a real villain and told Abrashenka, ‘You are a young man, you are not allowed to eat too much chocolate!’ He was obedient and gave me his portion. Mother said, ‘For shame! It’s for Abrashenka, you have already had your piece!’ ‘But Mommy, I like them so much!’ ‘At this rate, I will give you mine.’ Everything was for us.

Now I am going to tell you about the personality of Jews from Courland. We had a totally different mentality. It is difficult to describe; it must be felt inside. Ours is, in all aspects, another culture. For example, let us compare Jews from Courland with those who live in Latgale [Latgale is a province situated in the South-East of Latvia]. We are precise, punctual. The influence of German mentality is noticeable. German literature, music and culture have influenced Jews from Courland. I don’t mean to say that everyone in the Jewish community of Courland was an intellectual – far from it. But our community, our social circle, I mean my family, my classmates, we had a German upbringing.

I think there is nothing in common between culture, music and Fascism. They are different things – culture and Fascism. I still read German books. I adore German music and German hits [so-called ‘Schlager’]. My mother used to sing German hits when cooking dinner in the kitchen. I like the German language, but I hate the Germans with all the energy of my soul. I never could forgive them for what they did to me. I lost everything at the age of 15. The only treasure I possess is my daughter Rita. I despise those who had been imprisoned in concentration camps but now go to Germany ‘for a piece of bread.’ [Editor’s note: Since the fall of the Berlin wall, about 200,000 immigrants from the former Soviet Union have come to Germany as contingency refugees, those who could prove Jewish ancestry and therefore gained a status that almost guaranteed a visa to Germany. Most of these people were motivated by a desire for better material conditions.] They sell their souls. I am offended by them. I cannot imagine that it would ever be possible for me to go to Germany. I am Daddy’s girl, in spite of my likeness to Mother. I never liked the idea of going away anywhere. When, after the concentration camp, my second cousin Lea applied to go to Palestine, I said, ‘What would I do there?’

There were great villas in Courland. Each one was prettier than the next. On the right, there was Grobini, on the left – Ilgumezh. It was a wonderful place. A lot of Germans used to live there; Germans first came to Livland [the old name of Latvia] in 1201. Once we rented a bungalow there. The hostess was a German baroness; she let large rooms with a balcony. We rented bungalows every year in different places in the forest near Liepaja.

During the war

My childhood was wonderful, but it ended abruptly when I was 15. I could never imagine that all my family would be shot. My father was shot on 24th July 1941, but we didn’t know that. Maybe it would have been possible to evacuate then. My mother wanted to flee, but I insisted that not a step be taken without my father. And what was the result? I stayed alive but they were lost. God!

How I adored Daddy! I hoped that maybe he could be the one of a thousand or more people evacuated from Liepaja. I couldn’t even imagine the death camps. I thought: when the Germans come, maybe I won’t be allowed to study. My mother read the newspapers and she was shocked. Germans had been thought to be cultured people. I couldn’t have imagined it at all. I would lose my father in the space of a few days and become orphaned within the coming months. My mother, brothers, Granny and other close relatives were murdered on the Chanukkah holiday, 13th December 1941.

On that day, Mother collected everything when policemen came to take us away. They told us, ‘Take your pillows and blankets with you.’ I asked them, ‘Are you going to take me away, too?’ They replied, ‘We don’t have enough room. We will be back tomorrow for you.’ They came back the next morning at 5am and took me into custody. When I saw the prison site it became clear to me where my father, mother, Granny, brothers and sisters were. It was icy, about minus 30 degrees, deep snow, but people stood in nightdresses, with bare legs! It was horrible. How could I get out of that prison?

Policemen led me to the prison’s warden. Can you imagine who he was? He was our stableman, Krastins. He said, ‘What are you doing here, Bella?’ I replied, ‘I don’t know, they brought me here.’ He said in turn, ‘Go home quickly.’ Then he ordered the policeman, ‘Take this girl back home and not so much as a hair on her head is to be touched.’ Mother, Granny, Aunt Paula and my little brothers had been taken to be shot instantly.

I went home, washed myself and then went to work; there were kitchens in the military camp. Later, when I went back home after work, I understood everything. Jews had been shot from the very beginning. From 22nd June 1941 2, there were seven days of shootings. My father was caught in the city center when he came back after work, and was shot. Mass shootings took place in December 1941, near the seashore, too. The name of the settlement is Shkede; it was about seven kilometers from the military camp. Only when I was imprisoned, did I understand that my Daddy had not been put in the camp, he had just been shot. It was a shock, a very big one for me. I loved my father so much, and he loved me, too.

When I was living alone, two Jewish women took me in to live with them. Another action was organized in February 1942 and they came at once. I had a special document about my working for the Wehrmacht [German Armed Forces] in the kitchen at the military town. There were neither SS nor SD units in the military camp. The German soldiers were afraid of such units themselves. [Editor’s note: SD is short for ‘Sicherheitsdienst’ (Security Service), the intelligence agency of the SS.]

We did different kinds of work. I carried things, cleaned, washed windows. I mended socks for soldiers, trying to remember what my mother used to do and repeating her actions. I was a free workforce for them. They had to pay Latvians for work but they didn’t pay me. They gave me cigarettes, bread and bacon. I exchanged them later for different products.

The Arajs 3 and Cukurs 4 commandos of Latvian volunteers came for us in February 1942, with armbands around their sleeves [to signify death]. They came with punishment gangs from Riga to Liepaja. And they wrought havoc! On 1st June 1942, when everybody had already been annihilated, and there were only 800 of us left from the ten or eleven thousand Jews in Liepaja, they made a ghetto: Barenu Street, Kungu Street, Darzu Street and there was barbed wire all around it. We went into it. These houses had belonged to a Jew named Lucin before. They [the Lucins] were deported on 14th June 1941 5 6; they weren’t in the ghetto. Latvians and Germans guarded us. The commandant was a German. We were led to work in columns.

The ghetto was liquidated in 1943, in October. We were herded into rail freight-cars and sent to Riga, to Kaiserwald 7. It was a very large concentration camp. Jews were in there, and Poles and Germans also. But these Germans were criminals. Later we were sent to work at the Electro-mechanical factory; it is better known as VEF. We lived next to the factory. The weather was terrible – frost, rain, cold. We starved everywhere we went. But Germans lived at the factory, where it was warm and clean.

In September 1944 we were loaded onto a large steamship and were taken up to Danzig [today Poland], and then on barges we were taken to the death camp of Stutthof 8. I begged God all the time not for freedom, but just to be moved to another camp. SS men used to wander around during the day, writing down people’s numbers and in the evenings, around nine o’clock, they called out the people by numbers and we never saw them again. The crematorium was working day and night.

On 25th January 1945, the Russians 9 liberated us. They wanted to shoot us at first. But there was one woman from Daugavpils with us, and she spoke Russian to the soldiers: ‘We are from a concentration camp! We are Jews!’ We lived in their division for three weeks. It was cold and uncomfortable. A young soldier said to me, and I understood: ‘Will you eat?’ I was hungry enough to die. And he brought each of us a loaf of bread and a pot roast. We hadn’t eaten for so long! I devoured the offered food. The elder women were cleverer than I was – they ate slowly. And at night, it hurt so much I thought I would die! The surgeon came, of course, and I was given lots to drink, and was brought back to life!

Life after liberation

Then we went to Lublin [today Poland]. There was a Jewish community there. At Pesach we baked matzah to earn money for food. And on 27th April 1945 I arrived back in Riga, though there was still war raging in Liepaja 10. My heart pulled me home. Perhaps, if Englishmen had liberated me, like my second cousin Lea, I would have left for Palestine. Russians liberated me and I went home. I knew that I would go to VEF [Valst Elektrotechniska Fabrika, aka Riga VEF Radio Works] to work. I was without documents, but I told the personnel manager of VEF who I was and he accepted me for work. I went to live in a hostel. I didn’t get a passport, but I got a paper for three months, then for a year. When I was called to the NKVD 11, they stared at me. They asked, ‘Why have you remained alive?’ 12

I knew that I would work at VEF. I didn’t plan to return to Liepaja. Who was I going to look for there? There was that man in the plant’s personnel department, he seemed to have suffered a lot from the Germans as well, so I told him who I was, and he gave me an order for a place at a hostel. They refused to issue a passport to me, but preferred to prolong the temporary identification every three months. A few times I was summoned to security bodies and asked, ‘Why did you survive?’

I got married in 1948. My husband and I were very poor, but we loved each other very much. We had problems with accommodation. At first I lived with my husband Serapion [Bogdanov] – I called him Sergey – at his mother’s place. It was an old house, during the war there was a ghetto there 13 14. A large room, a large kitchen. My husband and I lived in the kitchen, we had screened off a corner, and his brother with his wife and children lived in the large room. My husband was the youngest in the family. Later we lived in rented apartments. We rented one in a private house on the very bank of the river Daugava. The landlady used to breed chickens there once.

I got married at the age of 22, and by the time we moved I turned 30, and I had to think of a baby. And so in 1957 Rita was born. Аnd in 1961 we were given this apartment by VEF. We had a boat, we used to travel down the Daugava and have picnics. We enjoyed our life!

After the war I couldn’t study anymore and I didn’t want to either. I had to earn money for bread. I was young. I wanted to enjoy myself, to dance. What happened to me later is a different story. I started to work at the big VEF factory. I worked on the large telephony equipment for 40 years and in one brigade for 29 years! And my husband also worked at VEF. My husband was from Rezekne [242 km east of Riga, in Latgale province], a Russian from an Old Believers 15 family. I have lived a wonderful life with my husband. We always celebrated all the holidays – Jewish and Orthodox Christian. If there hadn’t been a war, everything would have been different! I probably wouldn’t have married a Russian.

My husband and daughter

My husband was born on 19th July 1928, near Rezekne. When he was only one year old, the whole family moved over to Riga, but their father died two years after that. His mother was left with five kids. My husband was very handsome. I sort of taught him how to behave, remembering how my Mom treated Dad. I remember how Dad had given Mom a golden ring with a diamond on the 10th anniversary of their marriage. Sergey used to always bring me a huge bunch of roses on the 28th of August, the day of our wedding, wherever I was – in the sanatorium near Riga or somewhere else. He liked my hair, it really was beautiful, wavy. When Sergey worked in the second shift and I – in the first, I would often visit a beauty parlour. And he asked me not to go to bed before he came home – he wanted to see my coiffure.

I buried him not in the Old Believers’ cemetery, but in the municipal one, because he didn’t go to the confessor. They sang ‘Ave Maria’ and ‘Shine, my star, shine’ in the chapel. In spite of having lived without him for these last twenty years, I still miss him so much!

My daughter Rita, born in 1957, graduated from the Latvian University, from the Department of German Philology. She works in the State Historical Archives. When she received her passport, my daughter wanted to be noted as Jewish 16, but I talked her out of it. It was difficult for the Jews in the Soviet times 17.

Rita is my joy, my happiness. She was brought up by Sergey’s mother, because I worked. Sergey and I talked Latvian between ourselves, for I didn’t know Russian. But I learned Russian later. I speak only Russian with my Ritulya. I was somehow unable to talk German to her, the language spoken to me by my mom. Sergey loved Rita very much. As much as my father loved me. They liked each other a lot. He was very proud of her and of the fact, that she was the first of the Bogdanov family to obtain higher education. When Sergey died, I was worrying about her health.

Glossary:

1 Ulmanis, Karlis (1877-1942)

the most prominent politician in pre-World War II Latvia. Educated in Switzerland, Germany and the USA, Ulmanis was one of founders of Latvian People's Council (Tautas Padome), which proclaimed Latvia's independence on November 18, 1918. He then became the first prime minister of Latvia and held this post in several governments from 1918 to 1940. In 1934, Ulmanis dissolved the parliament and established an authoritarian government. He allowed President Alberts Kviesis to serve the rest of the term until 1936, after which Ulmanis proclaimed himself president, in addition to being prime minister. In his various terms of office he worked to resist internal dissension - instituting authoritarian rule in 1934 - and military threats from Russia. Soviet occupation forced his resignation in 1940, and he was arrested and deported to Russia, where he died. Ulmanis remains a controversial figure in Latvia. A sign of Ulmanis still being very popular in Latvia is that his grand-nephew Guntis Ulmanis was elected president in 1993.2 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.3 Arajs, Viktors (1910-1988)

major in the Latvian security section and was promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer. He was awarded the German medal ‘Kriegsverdienstkreuz mit Schwertern’ -- war service cross with swords. One must say he ‘earned’ it. In the first days of July he formed a group, known as the Arajs Commando, that roamed from city to city brutally settling accounts with Jews. When the German administration organized the extermination of Jews ‘in an orderly fashion’ (in geordneten Bahnen), Arajs made sure that his men were not left without work in the new arrangement. He personally shot Jews in the streets of the Riga ghetto and in the Rumbula forest. After the war he hid in Germany under an assumed name but was found out and sentenced to life imprisonment at a trial in Hamburg.4 Cukurs, Herberts (1900-1965): in 1919 was a Bolshevik sympathizer. In independent Latvia he became famous as a pilot; between 1924 and 1936 he designed and constructed a glider and three airplanes. In 1933-1934 he flew from Riga to Gambia and back in one of his own planes, the C-3 (Gambia in West Africa, had been a colony of the Duke of Kurland in the seventeenth century). Two years later he flew from Riga to Tokyo. He also visited Palestine, and his reports of the visit were colored with strong anti-Semitism. As soon as the German army entered Riga, Cukurs joined those who were shooting Jews. At the end of 1941, he personally participated in the shooting in Riga’s ghetto and Rumbula, killing infants and dancing with joy by the graves. After the war Cukurs found refuge in Brazil, running a boat and plane rental service on the Rio de Janeiro beach, and later owned a banana plantation. On 24th February 1965, he was killed in Uruguay’s capital Montevideo by members of a secret group called “Those who do not forget.” It is said that they were Israeli Mossad agents.