Cilja Laud

Tallinn

Estonia

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of Interview: March 2006

I met Cilja Laud during my first visit in Tallinn. The chairwoman of the Jewish community of Estonia 1, Cilja assisted me with my visa and then arranged the interviews with the members of the Jewish community. Cilja is a petite lady with cropped fair hair. She looks elegant in her nice clothes and light makeup. When I saw her for the first time, I felt her briskness coming from inside and also passing on to the people surrounding her. Cilja moves and talks quickly. She thinks fast and it does not take her long to make decisions. At first I took Cilja as an emotionless business lady, deeply immersed in the problems of the community. On the weekend Cilja called me and suggested that I should spend a weekend with her husband Rein and her. First we went on an excursion to the historic center of` Tallinn, and then took a trip to a typical small Estonian town, Rakvere, where Cilja had some relations with the Jewish community. Cilja and Rein picked me up at the hotel and a day of indelible impressions started. Cilja's husband is tall and stout and kind of sluggish. I understood that they had much in common. Both of them have a wonderful sense of humor, similar tastes and common interests. They are very sincere, outgoing and kind people. Cilja showed me Tallinn with pleasure. She knows the town and loves it very much. My trip to Rakvere was very interesting as well. On our way Cilja told me a lot about Estonia, about past times - before the annexation to the USSR. Both Cilja and Rein told much about the true history of Estonia, not the way it was covered by Soviet ideologists. At that moment I saw another Cilja: attentive, joyful and outgoing. In the evening Cilja and Rein took me home and introduced me to her mother right away. Anna Perelman has been bed ridden for several years - she had femoral neck fracture. Again I saw other traits in Cilja: a loving and caring person, for whom her mother was the most important person in her life. I could see it in her eyes when she was talking to her ... When I interviewed Cilja a year later, her mother had already passed away. She and other family members will be always remembered by people and in the conversation of Cilja Laud.

My father's family history

My mother's family history

Growing up

During the War

After the War

Going to school

Jewish life

Life after the War

Glossary

My father's family lived in Parnu [about 140 km south of Tallinn]. I do not know anything about my paternal grandfather, Abram Perelman. Even my father did not remember him. He died young and my grandmother, Genya Perelman, became a widow when she was 24 having three little sons. I do not know when Father's elder brother, Simeon, and the younger one, Yakov, were born. I can only say that the difference in years was not essential. My father Isaac was born in 1904.

Grandmother did not have anybody to help her. She had to provide for her family and raise her sons. She did not have any profession as she became a housewife after getting married. Grandmother had some close friends in Tallinn and she decided to move there. She said all women in her family loved cooking and were very good at that. Grandmother told me that she was eager to become a professional cook in Tallinn, but she could not study as she was supposed to provide for her family. Thus, she was hired as an assistant by the owner of the Jewish canteen. She learned things on spot and soon she became an excellent cook. The owner valued her so much that she bequeathed the canteen to Granny. When the owner died, Grandmother took over the business.

Grandmother ran the canteen very well. Grandmother was not just a very good cook, but she also loved her business. Rich Tallinn Jews often came to her and she had pretty good earnings. Over time she managed to buy the first floor of the building located at Lejke Karja Street in the center of Tallinn. The family lived there and Grandma called the restaurant Bialik club 2. It was not a canteen, but the place where Jewish intelligentsia got together. People came there to enjoy good food and to share political and cultural events. At times famous people came there. It seems to me that they mostly came there for good food as grandmother was an amazing cook and confectioner. Some Estonian Jews still remember her meat patties and gefilte fish.

Of course, Grandmother used traditional recipes, but still she added some zest in all her dishes. She always cooked gefilte fish herself. She did not cook the whole fish, but stuffed separate pieces. She put the pieces of dried white loaf at the bottom of the pot and put rounds of beet there and then fish on the top. Then she put a piece of carrot on each piece of fish and then added a little bit of water there. Then she placed it on the platter in a fancy way. Tallinn Jews called her gefilte fish - 'fish Frau Perelman.' Many newcomers came over to her to eat her fish. I still cook fish by her recipe.

She also had her own recipe of liver pate. She did not boil the liver like most cooks do, but she fried it in the source-pan for about two minutes. Then she minced it and added fried onion. Then she added three spoons of cognac to every kilo of pate and two to three minced boiled carrots, then she mixed it all up thoroughly. The pate turned out to be very fluffy and tender. Grandmother adorned it with grated boiled eggs - whites and yolks separately.

Grandmother always made sure that her dishes were not only tasty but nice looking. It was taken for granted that there was a lot of food on the tables of Jewish families. Grandmother also wanted the food to be nicely served. Jews are a wonderful nation - apart from their own customs and traditions, they naturally and organically take up the customs and lifestyle of the people who are surrounding them. Estonians are very cultured. Estonian ladies intuitively feel how they should serve the table, furnish the room, where to place a vase, how to match things depending on the occasion. My grandmother was also very good at that. All looked beautiful in her place and fit the occasion perfectly.

Even her looks were stylish - I should say she was commensurate though she was heavy. At that time there were other beauty standards and men liked plump ladies. She was not a beauty, but still she was attractive. I think there were suitors who wanted to marry her even despite three children, but Grandmother did not want a stepfather for her children and remained alone. She was very brisk. Being a widow for 24 years, she managed to provide food for her children, raise them and even pay for their education.

All Jewish holidays were marked in the family. Grandmother cooked festive food not only for her family. It was a busy season in her restaurant. On the eve of the holidays Tallinn Jews did not only come to Bialik club to have meals but they also ordered meat patties, gefilte fish, forshmak and liver pate to go. Those were Grandmother's specialty dishes and she cooked them herself. So, she had a lot to do before the holidays.

During the holidays she took a rest and her restaurant was closed down. She marked holidays at home strictly in line with the traditions. On holidays the whole family went to the synagogue. Seder was traditionally carried out as well as kapores on Yom Kippur. She fasted on that day as well. Not only family members were invited for holidays. If Grandmother found out that some Jew had nowhere to go for celebration - either because of being lonely or a visitor to Tallinn she always invited them to join us for a holiday.

At home Grandmother spoke Yiddish with her sons and Father was fluent in that language. Of course, he was also fluent in Estonian as he lived among Estonians. At that time no Jew would ever think that one could live in the country without knowing the state language.

Grandmother sent Father's elder brother Simeon to Riga. He entered the university and studied journalism. After schooling he came back to Estonia. He worked for an Estonian newspaper as a journalist. He married a famous Estonian ballet dancer, Anna Exton. She was the soloist at the theater 'Estonia' and was fluent in seven or eight languages. She was an amazing person. After her performances she mingled with the audience and thanked them in all languages she knew. Simeon and Anna were childless.

When Estonia became Soviet in 1940 3, Simeon Perelman was named the editor of the paper 'Soviet Estonia.' When World War II was unleashed, Germans occupied Tallinn in September 1941. Several hundreds of Tallinn's male Jews were shot in Patarei prison. Simeon was among them as he was a communist in his heart and the editor of the newspaper. During the war Anna was in evacuation. She returned to the 'Estonia' theater after the war. First she was a prima ballet dancer and then became one of the principal choreographers of the theater and staged ballets. Her ballet 'Red Poppy' was very popular and she always got standing ovations from the audience for it. Anna died relatively recently, about eight to ten years ago.

I do not know what Father's younger brother Yakov did for a living. I did not communicate with him that much. He died young. I do not know where he studied either. Yakov's wife's name was also Anna. I do not remember her maiden name. They had an only son, Gennadiy. His Jewish name is Gedalie. He was Anna's son. Yakov was his stepfather. Yakov married Anna when she was pregnant from another guy. At that time it was a great disgrace when a baby was born out of marriage, so Yakov decided to marry her to save her from disgrace. He loved her dearly and treated the baby like his own son.

Anna never worked. She was cheap, flirted a lot, but Yakov forgave her all the time as he loved her. During the war Anna and her son were in evacuation and Yakov was in the lines. When he came back from the front he was sick for a while and died in 1947. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery. There is no date on his tombstone. We even do not know exactly when he was born. There is only the date of his death.

After Yakov's death, Anna got married for a couple of times and took to the bottle. My father literally saved Gennadiy from his mother - a drunkard. Her last husband was a colonel. He served in Estonia. His name was Levin and Gennadiy took his stepfather's name. It was a shock for my father as Gennadiy remained the only one who carried our family name, Perelman. I did not have children and Father really hoped that Gennadiy would continue the Perelman line, but not all people are thankful. Gennadiy became Levin and we stopped keeping in touch. We greeted each other and talked as if we were not relatives. We did not have any ties with him.

When Gennadiy became mature, he found his birth father. Now Gennadiy is living in Baltimore, the USA. I do not keep in touch with him. I could not forgive his meanness towards Yakov, who had been an excellent father to him all his life, even better than some of the birth parents are.

I do not know much about Father's childhood. He studied in Leipzig, Germany, at some point. I do not know why he came back. Upon his return he became the apprentice of a glover. Father was very skillful at anything he did. He became an excellent glover.

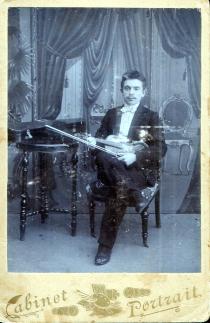

Since adolescence he had the nickname Prince. He was called Prince by his young friends and the nickname remained. He was very witty and a great storyteller. Everybody liked to listen to him. He was fluent in three languages and then he also learned Russian. In all languages he spoke his humor was a specific characteristic of the language. Father never took any music classes, but played the violin wonderfully. When I was in the senior grades at school, he could so easily resolve algebra tasks that it greatly surprised me. He was a nugget having an amazing, open mind. He was also very kind, always ready to help his friends and strangers. He remained like that till the end of his days.

And now about my mother's family. My maternal grandfather, Abram Kaplan, was born on 16th September 1874 in Estonia, in Yamburg. I do not know anything about grandfather's family. When he was young he moved to Narva from Yamburg. He was a very good tailor. My grandmother, Anna Kaplan, nee Pertsovskaya, was born in Saint Petersburg on 27th January 1884.

There was a pale of settlement in Russia 4, and Jews were not permitted to live in big cities, including Saint Petersburg, but still there were exceptions. My grandmother's grandpa was a cantonist 5, who upon decommissioning from the army, were entitled to settle in any city they wished. Besides, the tsarist government gave them money for husbandry and housing. Thus, Grandmother's grandpa happened to be in Saint Petersburg. His children and grandchildren also settled there. The family was religious. All Jewish traditions were observed and all kids were raised Jewish.

They had five children. The elder was Elisabeth. Then my grandmother Anna was born, and after her - sister Sofia, brother Simon and sister Ekaterina. All of them were very beautiful and well educated. They had a good ear for music and wonderful voices, but only Sofia became a professional singer and entered the conservatoire. Grandmother's only brother Simon became a jeweler. Simon lived with his family in Leningrad. He had an only son Alexander. Elisabeth remained single. She did not work and the relatives provided for her. Sofia married a Muscovite and moved to Moscow. Her husband's name was Boris Narvo. He was an architect. They did not have children. Boris was very jealous and did not want his wife to work. Sofia had to become a housewife. Ekaterina lived with the family in Tallinn after the war.

My grandparents met accidentally. Grandmother came to Narva for a visit. One day she came to see some Jewish family, where she met Grandfather. She was a very beautiful, clever and witty lady. Grandfather was also handsome. Shortly after they met, they fell in love with each other. Grandmother's parents were not against her marriage and soon the wedding took place. Of course, they had a true Jewish wedding as it could not have been otherwise at that time.

After the wedding Grandfather took Grandmother to Narva. My mother was born there in April 1910, but the entry in the synagogue registry was made only in August. She was named Chana. The second daughter, Nessie, and the youngest, Assia, were born in Tallinn.

I do no know why my grandparents decided to move in Tallinn. Maybe Grandpa decided that he would have more customers in Tallinn. If that was the case, he was right. Very soon he had his own workshop and regular customers. The family was well-off. Grandpa was the bread winner, and his earnings were enough for the family. Grandfather bought an apartment on Viru Street in the center of Tallinn. It consisted of 13 rooms and occupied the entire floor. Apart from the apartment in Tallinn, Grandpa also bought a summer house in Lakhti, Finland. It was in the resort area. Grandfather had a yacht. In the summer the whole family took a voyage on the yacht over the weekends.

The whole family was fluent in Estonian, Finnish and German. Of course, everybody spoke Yiddish. The grandparents and my mother also knew Russian as they lived in Narva for a while, which was a Russian-speaking town as it bordered on Russia. Aunt Nessie was fluent in English.

The three daughters studied at the lyceum. The younger one, Assia, died at the age of eleven from a children's disease. My mother and Nessie graduated from lyceum and entered Tallinn conservatoire. Both of them were very musical; they probably took after Grandmother. In a couple of years Mother dropped her studies, but her sister Nessie got a diploma and became a pianist. Nessie married a Jew from Tallinn, Paul Goldman, and had three sons.

I do not know exactly how my parents met. Probably, it was in a natural way as all Tallinn Jews knew about each other. I know the story about their wedding as mother told me about it. It was an unusual story. They got married in 1936 after they had known each other for several years. They met at dancing parties and in the theaters. At first, they did not pay much attention to each other. Dad was shorter than Mother and she did not even look at him. Father wanted to be free and remain a bachelor. He liked partying, noisy companies. He often went to the clubs, restaurants. Apart from his short height he was an interesting man. When he started talking, everybody was enchanted. Maybe that was the reason why mother took an interest in him. She was very stylish and elegant, used to bossing men around. She was not used to be refused in anything.

Of course, Father liked Mother, but not to such an extent to give up the lifestyle he was used to. Once Father mentioned it to Mother. She responded to him, 'Never mind, my love would be enough for the two of us.' Mother often told me about it and I remembered that phrase. After that Father married Mom. Then he fell in love with her after they got married. He loved her all his life and admired her. He helped her about the house, saw her to and from work. He never forgot about the flowers. Mother was a very poor cook. Before the war the food was cooked by maids and when we came back from evacuation, Father started cooking for us. He was a great cook. I think he got it from Grandmother Genya.

After the wedding my parents rented an apartment in downtown Tallinn, on Bruksi Street. Mother was a housewife. I was born in 1938 and named Cilja. Though Mother was a housewife, I had a baby-sitter since I was an infant. She was German, Frau Opperman her name was. She was very strict. She was not pleased when I was chatting with my parents, nothing to speak of my grandparents. Opperman raised me very strictly and feared that they might spoil me. Of course, when I spent time with them, they really pampered me. Mother said that Frau Opperman loved oranges. Thus, Grandpa brought oranges to Frau Opperman for her to allow me to go for a walk with him or go to see my grandparents. In that case, she could not say no to him.

I do not remember much about my prewar childhood in Tallinn. I remember sitting on the lap of Frau Opperman, who was reading books to me. I can recall how my parents took me to the zoo for me to see the animals. I also remember the walks along Kardiorg Park with my father. I also remember that I was a bad eater, but Frau Opperman always made me eat all the food on my plate. When she turned away, I hid the food under the table cloth. When she left the room I threw the food out the window or to the roof of the neighboring house.

I must have been started speaking German as I spent a lot of time with my baby-sitter. I spoke only German before we left for evacuation. Of course, my parents were fluent in German, but they often spoke Yiddish. In general, many languages were spoken at home.

I would like to make a digression and talk about Estonia before the 1940s. Even at the time, when Estonia was a part of the Russian empire, there was no anti-Semitism here. There was no pale of settlement and admission quota at the universities 6. That is why there was Jewish intelligentsia in Estonia, not just a few representatives like on the rest of the Russian territory. Most Estonian doctors, musicians, lawyers, engineers were Jews. It was not like that in other Baltic countries. It was distributed as follows: Lithuanian Jews - craftsmen and dealers, Latvian - traders, but Estonian - Jewish intelligentsia.

In Estonia there was not such a notion as townlet, which was mentioned by Sholem Aleichem 7. Jews lived everywhere, in all Estonian cities. They were not clustered in some areas which were meant solely for them, but settled mostly downtown. They stuck together. It is noteworthy to mention that after 1918, when Estonia gained independence 8, there was no state anti-Semitism. Even in everyday life it was very weak. There was a café in Tallinn where even in Estonian time Jews were not permitted to enter. At the same time there were Jewish clubs, which were closed for Estonians.

In 1926 the Estonian Jewish community got cultural autonomy 9, granted by the Estonian government. Cultural autonomy streamlined the development of the Jewish community of Estonia. Estonian Jews had self government, which was headed by outstanding Jews: the director of the Tallinn Jewish lyceum Samuel Gourin, Tamarkin, Eisenstadt and other worthy people. Those people revived Jewish life. There were all kinds of Jewish organizations, 32 in total. There were student Jewish organizations in Tartu as well as a mutual aid fund, wherefrom poor students were provided money for tuition donated by rich Jewish families. Thus, Jewish life in Estonia was fully-fledged.

Of course, religion was an essential part of life for Estonian Jews. The synagogue united all Estonian Jews. I think there was not a single Jewish family, where Jewish traditions were not observed and where children were not raised in a religious spirit. There was a wonderful synagogue in Tallinn 10. It was crowded on holidays. It goes without saying that there were Estonian, Russian, German and Jewish schools. Everybody could choose what school to attend and what language should be spoken, but all Estonian Jews spoke Estonian. Of course, I know all those things not from my own recollections, but I just wanted to speak about it for people to have an understanding what type of childhood I had. I think it will help people understand what Estonian Jews were like.

In 1940 Estonia became a Soviet republic. Of course, my parents were not happy about it, but what could they do? They had to adapt to the reality. Probably, Father's elder brother Simeon was the only one in our family who welcomed the Soviet regime as he was a hard-boiled communist. The rest of us just abided by that. There were a lot of newcomers from the USSR. They were to settle somewhere. The new regime took the houses from the owners, and strangers were housed in large apartments, where only one family used to be living. Our apartment was also turned into a communal one 11, two or three families moved in there. Then, we found out that it was not the most horrible thing.

On 14th June 1941, 10,000 Estonian citizens were deported from the country 12. Maybe that number does not seem so big as compared to those repressions that took place on the territory of the Soviet Union [see Great Terror] 13. It should also be noted that the entire population of Estonia was only about a million at that time.

Fortunately, our family was not affected by that. It is amazing that it went past us. There were no rich people in our family: Father was a glover, that is, a craftsman, Grandfather was a tailor. They did not have anything, but the family of Mother's sister Nessie, the Goldmans, were deported. They were wealthy, and such people were considered enemies by the Soviet regime. The whole kin of Paul Goldman was deported: men were sent to the Gulag 14, women and children were exiled. Maybe, finally they would reach us, but on the 22nd of June 1941 German troops invaded the territory of the USSR. The Great Patriotic War began 15.

Father was mobilized almost right away, but not in the lines, but in the city of Kirov. There were plants, where military uniforms were made and Father was in charge of the glove making department for the Soviet army. He spent all the years of the war there and all we could do was write to each other. We left for Ural, Nizhnyaya Uvelka, along with other Estonian Jews. We took the last train. Mother's parents and Grandmother Genya went with us. I hardly remember the road. I remember a huge crowd at Tallinn train station. Mother carried me and I leaned against her shoulder. The rest was like in a haze.

I remember our life in evacuation in Ural very well. When we reached Nizhnyaya Uvelka, Mother took me by the hand and we went looking for the rural administrative building. It was the place where they were supposed to tell where our family - my grandparents, mother and I - were to get settled. I remember poor rustic ladies looked at my mother as if she was a wonder as she was wearing high heeled shoes, posh clothes, a silver fox fur and a hat. Finally, my mother found the rural administration building and we went to the place we were told.

I did not know the name of the hostess. She was not young. Like it was customary in Russian villages, people called her by the patronymic Kuz'movna. She gave us a poky room, which was still good for those times. Then Mother said that she was shocked when she saw some people sitting at the table, combing their hair and then pressing something. First, she could not get what they were doing, and then she understood that they took out the lice. She was so stressed that she remembered that till the rest of her days. Mother never forgot the kindness of Kuz'movna. She helped us a lot.

My grandparents were afflicted with typhus fever in Nizhnyaya Uvelka. Of course, there were no medicines and Kuz'movna treated them herself with some herbs, and healed them. She took care of Mother. Mom practically did not know anything about house chores. She even washed the floor for the first time in evacuation. She was 32, but it was the only time she did it. Each time she tried cleaning, some of the rural ladies told her, 'You, Anyuta, would better play the piano in the club, I will clean myself, you just smudge it more.' At that time there were no tape recorders, but young people, wanted to dance to music. Mother played the piano in the club during the entire period of our stay in evacuation. All people loved her. Grandmother cooked for us. Kuz'movna had a goat and she gave a glass of milk to me every day.

Though, I spoke no Russian at that time, I made friends with Kuzmovna's younger son Ivan. He was several years older than me and took care of me. As a result of our friendship my first Russian words were expletives. He did not scold me - it's just that all villagers were swearing. Now I understand how funny we must have looked together - a village boy and I wearing a white fur coat and a bonnet. Mother dressed me the same way as in Tallinn. Here I had the same habits brought up by Frau Opperman.

Mother told me how in those years of hunger and cold, when she could hardly get me the eggs, I refused eating them, as I demanded that she should give me an egg saucer... I could not eat them without that. That story was included in our family anecdotes and Mother often used to tell people that anecdote and they would laugh about it. In spite of my speaking German, people treated me very well. In general, I can say that people from the Ural are very kind and warm. Grandmother's sister Elisabeth came to us from Leningrad. Unfortunately, she did not live with us for a long time as she died in 1943. She was buried at the cemetery of Nizhnyaya Uvelka.

Our hostess Kuz'movna really saved our family during occupation. Upon our return to Tallinn, Mother did not forget about it. For one, she always kept in touch with her and once, in 1956, she invited her to come over to us. The people in the Ural had a worse living than the very needy ones in Tallinn. Of course, my parents bought her a whole bunch of clothes and other presents for her and her relatives.

We got food cards 16 during the war, but the products which were given were not enough. We starved at first, but then my grandfather Abram Kaplan, who was a tailor, became a bread-winner for our family. He got another qualification and started making military uniforms. His customers were high- ranking officers. He became a brilliant specialist and he had a lot of clients. They paid him mostly with products, so we were not starving any more. After the war Grandpa kept sewing military uniforms. I remember General Soloviov in particular. He recognized only grandfather's work and came only to us for fittings.

When Tallinn was liberated from the fascists in 1944, Mother's sister Nessie and her son were the first to return home. Her husband Paul, the only Goldman who escaped deportation, was at the front. He was drafted into the Estonian corps 17. He came back crippled from the front. His leg was injured and he had osseous tuberculosis. His disease was progressing fast and Uncle Paul could walk only with crutches.

Soon we went over there. Nessie lived in the grandparent's apartment on Viru Street, but we were given only four rooms out of 13 we had. The rest of the rooms were occupied. My baby-sitter Opperman managed to preserve part of the bedroom furniture and table silverware. The rest was taken by those who stayed in Tallinn. We became practically indigent. Father was still staying in Kirov. They did not let him leave the plant, and he came back home only in 1947.

We were very needy. Grandfather was the only bread-winner. Father stayed in Kirov and we did not know when he would come back. It was hard. The silverware which Frau Opperman managed to save, was taken by Grandfather to the pawn shop for us to get by.

At that time Grandfather often started inviting a Jew who came to Tallinn from Moscow on business. His name was Simeon. He was a hatter and worked for the Kremlin and for Stalin as well. He was a very rich person. Grandfather started talking Mother into being with him. He said that she was too young and she should not wait for her husband for years, saying that she should think of her and me and accept the proposal of a decent man who would accept me like his own child. Such talks were frequent even in my presence. Grandfather insisted that Mother should divorce Father and leave with Simeon for Moscow. Mother did not want that. I do not remember all the details, but I feared that I might leave home and never see my dad, whom I loved so much.

Finally, Grandfather talked Mother into going to Moscow and take a closer look at Simeon and then make a decision. Mother and I came to Tallinn train station and I ran away home right before the train was about to depart. Since then nobody mentioned a trip to Moscow again. Later Father came back. The whole family was together. I was so happy.

My paternal grandmother Genya came back from evacuation. She got two rooms in the house, which she used to own before the war, that is, her club. Five more families were housed in the rest of the rooms. There were terrible anti-Semites, newcomers from the USSR, among them. The Yanu family were all drunkards. Grandmother had to hear the words 'kike mug' pretty often. There were debauchery and threats. In a word, the conditions were terrible.

It was just one filthy kitchen for five families, but one stove for all those people. There was a small partitioned part of the kitchen instead of a bath, and then our elderly neighbor died and Mother asked for permission to make a bathroom in her poky room.

Grandmother started baking pies to make some money for a living. When Tallinn Jews found out that Grandmother Genya had come back to Tallinn, they started asking her to make lunches at least. Grandmother was happy to do what she liked again. She even managed to open a small canteen in her apartment. Of course, it was impossible to do it officially during the Soviet regime, but Grandma was a very smart woman and she could make it so that nobody could find fault with her.

One room was occupied by Grandmother. There was a large table in the other one, where she served meals to everybody who came over. There were mostly visitors, whom she treated. Nobody said that they had to pay for her treat. Of course, if the authorities had found out that Grandmother had a canteen, and made money with that, they would have closed it down and fined her at best. But most likely she would have been put in prison as at that time private entrepreneurs were in disgrace as they allegedly hampered the economy of the country. People were sentenced for a pretty long term for that.

Of course, there were inspections: she explained that her prewar friends came over to her as they knew she was a good cook and she said that she treated them to food free of charge. If she had a chance to feed people, why should anybody care? Strange as it may be, that explanation was accepted. Some of the visitors came over two to three times a week. There were even some people who came every day. There were all kinds of people, even the most respectable Jews in Tallinn. Of course, Grandmother took money from people who were well-off, but she also helped a lot of poor people, and not only Jews.

Grandmother found out that a poor Jewish lady, Chasse Umova, and her daughter were living close by. They were very poor. Grandmother took her as an assistant and gave her a chance to make money and feed her daughter. Chasse's daughter Edit came to Grandma everyday and she was given the food for free. I made friends with her. We grew up together.

Grandmother also hired an elderly Russian man with one eye. He bought potatoes on the market, cleaned fish and did odd jobs. He was a drunkard, but Grandmother was sorry for him. She fed him and helped him out. Grandmother did not only help those who could work for her. If she found out that some of the local Jews had no money for food, she fed them. She helped them until they managed to provide for themselves.

Grandmother cooked herself. Chasse just helped her buy the things, pared vegetables, cut meat and vegetables, washed dishes. There was one cooker for all people in the kitchen and the neighbors cooked their food there during the day. Grandma cooked food for her canteen at night or early in the morning, when nobody was there. When her younger son Yakov died in 1947, Grandmother started helping his widowed wife and son Gennadiy with money and they had them move to her. The boy went to school, and Grandma fed him, bought him clothes and took care of him. She was very stalwart. Her energy and kindness were enough for everybody.

Grandmother did not leave her business even after she was sick. She was unwell. There was one period of time when Dad stayed there to look after her. Even at that time she did not close down her canteen. Only when I started working, making enough money to help Gennadiy, who was a student, Grandma closed down her business. At that time all of us provided for her. Genya died in 1960. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn. Of course, the funeral was in line with the Jewish rite. Even in Soviet times the Estonian authorities shut their eyes to that, though in Russia and Ukraine it was next to impossible to bury the person in accordance with the Jewish tradition. Those people who knew Grandmother, still remember her with kindness.

I went to school pretty late, at the age of eight. My Russian was very poor, with a strong accent, and I could hardly speak Estonian. Of course, after the war there were no German schools in Tallinn, only Russian and Estonian ones. At first, Mother decided that I should go to an Estonian school, but the teacher at elementary school, an Estonian, did not speak Russian, only Estonian, and I could not understand her.

Luckily, Mother transferred me to a Russian school, where the teacher was an elderly Jew. If I misunderstood something in Russian, she retold me that in Yiddish. Since Yiddish and German were similar I could understand her. I learned Russian over time. I also was well up at Yiddish. We lived with my maternal grandparents. If they wanted to conceal something from me, they started speaking Yiddish. Thus, I learned the language. Though, I speak Yiddish only with a Russian and Estonian accent, but still I am fluent in that language and my listening comprehension skills are also good.

I did pretty well at school. Mathematics was a stumbling stone for me. I am really bad at that. I had no problems with the arts. I had many friends among my classmates. I was a very active girl and always arranged some games. We liked playing war, where I was always a leader. There were girls among my friends, but still most of them were boys.

My classmates often came to our place on holidays or just for dancing parties or for a chat. Usually when kids come to somebody's apartment, they want their parents to leave, but it was vice versa in our case. My parents were loved. When Father started telling his stories, everybody paid close attention. They were never so attentive at the classes. They always asked Mother to play the piano. There was a huge grand piano in our room and Mother played both classic and dancing music.

It goes without saying that when the teacher made an announcement in the 3rd grade about joining the pioneer organization 18, I decided that I should do it right away. I even corrected my bad mark in arithmetic to join the pioneers as it was sacred for me! I was the class monitor and the leader of the chairman of the pioneer council of the class. Then I became an active Komsomol member 19 as I sacredly believed in the ideals. I was even the chairman of the Komsomol unit of our school. [Editor's note: Komsomol units existed at all educational and industrial enterprises. They were headed by Komsomol committees involved in organizational activities.] Strange, that that is what I did.

Father did not like Stalin and he never held it back from me. Father and his friends often said in my presence that we would be much better off without Stalin, called him blood-thirsty, told us about repressions, the Gulag. There was such a period in Estonia, in the late 1940s, when very few Gulag survivors started coming back. They spoke of the horror of Stalin's camps and it was hard to believe in that. Father understood clearly who Stalin was and explained that to me, though he warned me not to discuss those things with anybody.

Father was frank with the people who were surrounding him he must have said something what he was not supposed to and somebody informed against him. Father was arrested. I recall, I was on the way home from school and saw my father was walking towards me with two men accompanying him on both sides. I asked him where he was going and he kissed me and said that it might the last time we see each other. Fortunately, his fears were not realized. During the litigation he was not accused of political crime, but of larceny. Nobody believed that as they understood that it was connected only with the politics. He was sentenced for a long time, but he was actually in prison for two years and was pardoned. Father's friend Rachmiel Bloomberg helped him a lot while he was in prison.

In 1948, when campaigns against cosmopolitans 20 began in the Soviet Union, we did not have them, but we had the same collectivization 21, as in the USSR of the 1930s. Estonian peasants were compelled to join kolkhozes 22. They did not think that it was merely impossible for Estonians. They had a different mentality - they were used to live out of town at their own farmsteads and have their own husbandry. Though the land was very poor and stony in Estonia, the crops were high as Estonians are hard working people and put their heart and soul in work. People did not want to get united in one kolkhoz as it was strange for them.

Then Estonia started another deportation. Peasants were exiled to Siberia only for their desire to be the hosts in their own land, and do what they were good at. Entire Estonian families were deported and farmsteads were forsaken at first, but soon new hosts appeared there. Then they also deported those who happened to come from the exile in 1941. Not only men, but young boys were exiled.

In the post-war period Stalin issued an order to release from exile those who had vocational and higher education, though they were not permitted to live in Tallinn and other relatively large cities of Estonia, but still they came back home. And now in the late 1940s they were arrested and exiled again. Some of their relatives were still staying in exile. The second deportation referred only to the two above-mentioned categories. The rest were not touched.

The next wave of repressions started with the Doctors' Plot 23, but our family was not affected. We did not have doctors in our family. Nobody from our relatives worked in state structures. Though, Grandmother's kin from Leningrad suffered from that. Grandmother's distant relative worked for the Kremlin hospital and he was imprisoned. Though, shortly after Stalin's death, she was released from prison and rehabilitated 24.

I clearly remember 5th March 1953 - the day of Stalin's death. I was at school at that time. Our classes were canceled. All students were aligned and taken to Baltic train station. There was a monument to Stalin and we were supposed to sob there listening to the speeches and mourn over him. I felt happy. The school girls had navy blue and gold berets and I covered my face with the beret for people not to see that I was laughing. They must have taken my laughter for sobbing.

At home people took that even with relief. Father said, 'Finally! Now we will have another life and we can breathe freely.' Then there was the Twentieth Party Congress 25. Of course, I read Khrushchev's speech 26, when it was partially covered in the media. In general, I did not hear anything new as compared to the stories I heard from my dad. The only difference being that it was a prominent party activist saying that, not my dad, therefore I accepted it differently.

I thought Stalin to be a bad, tough man, but the ideology of communism was correct. I decided to be an active Komsomol member to fight for ideology not to be distorted. I wanted to be fair and consistent. I was childish and idealistic - what else can I say ... when I grew up I understood that communism pictured by a utopist was really wonderful, but it was an illusion, a nice fairy-tale for adults.

The events of the Twentieth Party Congress were not discussed at home. At times the adults would drop a phrase along the lines of 'it is good that the thaw started, maybe our relatives will have a better life in Russia.' My uncle Alexander could get the position of the first fiddle in Mariinskiy theater. He waited for a long time, and they did not take him because he started playing better, but just because it turned out that the nationality factor was less important. His wife managed to be in charge of the foreign languages chair at the Financial Institute in Leningrad after being an associate professor. We were not affected by that in any way.

Anti-Semitism appeared in Estonia after the war. However, it was not noticeable at the state level, because Estonians were at power there, who always treated Jews tolerantly. Though, there was anti-Semitism towards the Jews who came from the Soviet Union, and I think that the attitude was bad to them not because they were Jews, but because they were Soviet Jews. Anti- Semitism came from newcomers. We could hear things like 'kike,' 'Hitler failed to exterminate you.' Usually Estonians sharply reacted to that, not the Jews. They protected Jews.

The newcomers from the USSR were given the cold shoulder and treated ironically. From our point of view, the newcomers behaved at least strange. Officers' wives went to the best Tallinn restaurant, Gloria, wearing posh long nighties. They bought night gowns thinking it to be dresses as they had never seen anything of the kind before. They did not understand what a bidet was. One lady told my mom that Estonians were such fools as they did not understand that it was not convenient to wash one's hair in that bidet. They did not know what toilet paper was for and they used newspaper instead. They did not understand that they had to flush the toilet etc. The hostess could serve the salad to the guests in a metal pipkin and put an aluminum spoon there. An Estonian lady would never do that. There was no culture in everyday life. I even do not know how to put it - a totally different culture or the absence of culture. It was natural for them and wild for us.

I often thought why so many Jews stayed in Estonia during the war and did not want to get evacuated. Almost all Jews who stayed were exterminated by the Germans. Probably there were several reasons. At first, Estonian Jews were used to live close by with Germans. There were pretty many Germans in Estonia before Hitler called upon 'Volksdeutsche' to come back to their motherland. Jews always had a peaceful relationship with them. Many Jews were in Germany, and my father studied in Leipzig.

Therefore there was no fear of Germans. Probably people knew about the war in Poland 27, concentration camps, execution of Polish Jews. They must have known that for sure as it was broadcast by the radio, covered in newspapers. I understand that people thought that it was not referring to them. Like now I think that I have nothing to do with the things happening in e.g. Chechnya 28 or Afghanistan. It is there, but I am here, so it cannot affect me.

Maybe there was a likewise perception of the events that took place in Poland. I am sure, not many of the Estonian Jews believed that Hitler would exterminate the Jews until the third generation. The fear of the Soviets was much stronger than of the Germans after all those things that the Bolsheviks 29 had done for one year, after the deportation of 1941.

Many people must have hoped that the Germans would protect them from the Bolsheviks and Estonia would gain a normal course of life again. They were mistaken and paid with their lives for that mistake. As for Estonians, the German occupation was much easier on them than the Soviet one. Estonians have a lot in common with German traditions and culture.

After the war we were told that it was the Soviet army which liberated Estonia. Estonians thought that the Soviet army liberated Estonia from the Germans to occupy it. There is a grain of truth in both of` these statements. Estonians had their own perception of history and Estonian Jews theirs, and those who settled in Estonia after the war had their own. History is not black and white, it is multicolored.

It also refers to the fact that Estonian people were in two armies: the Estonian Corps in the Soviet army, and the Estonian Legion SS 30 in the German one. Estonian Jews were drafted into the Soviet army because of their beliefs - they wanted to fight fascism, fascist ideology and other Estonians had weaker ideas: they wanted to take the Germans' side and fight Soviet occupation. In general, Estonians, did not care which side they should take, as both of them were alien, but in their eyes the Bolsheviks appeared to be more dreadful than the Germans.

We have always been Jews. Even during the Soviet times we marked Jewish holidays in line with the calendar. On Pesach and on Yom Kippur I did not go to school. Mother wrote notes to the teacher saying that I either had a sore throat or abdominal pain. On those holidays I could not attend classes.

I also went to the synagogue on holidays. Our beautiful Tallinn synagogue was destroyed during the war. After the war the municipal authorities gave Tallinn Jews the premises for a prayer house - at first it was at the second floor of the automobile base, and then separate premises on Magdalen Street - a wooden hut with mice and rats. I went to the synagogue with Mother and Grandma, to the balcony. Men were to sit separately. I did not have such a kerchief as Grandma had and I put my pioneer scarf on my head.

Grandfather went to the synagogue rarely and after war he became an atheist. Probably he could not abide by the fact that God had allowed the extermination of so many Jews just because of their nationality. On high holidays, such as Yom Kippur, he went to the synagogue with us, but he refused putting on a kippah and wore a cap. He put it on, then entered the synagogue and stayed there for the service because of Grandmother, who had sincerely remained pious even after the war.

We almost always marked Sabbath at home. Grandmother cooked gefilte fish. It was not kosher as we did not observe kashrut after the war, but anyway it was a true Jewish dish. We marked holidays according to traditions. Even in the hardest times we had matzah. Grandmother made gefilte fish, strudel and baked hamantashen on Purim. Grandmother Kaplan made potato fritters by traditional recipe, but Grandma Perelman added fried onion there. They were amazingly tasty and nice looking - of golden color, not graying.

We lived in a very large room, 44 square meters. It was a rare thing in Soviet times. We did not put any partitions there. During my childhood we rode bikes in that room. On Pesach the whole family came to the Kaplan grandparents. A large table was set up for a big family reunion. Our family and Aunt Nessie with her family came over. Of course, during the Soviet time it was banned to mark religious holidays, and not only Jewish, but any religious holidays. Estonians also stealthily celebrated Christmas as it was banned by the officials. Both Jews and non-Jews marked their holidays and got ready for them beforehand.

If we could not get matzah for some reason, we baked it ourselves. Grandfather remade one of his tailoring gadgets to make matzah. The whole family was involved in the baking process. Grandmother kneaded the batter and we, kids, rolled it and pierced it with that gadget. Grandfather baked the matzah.

There was a woman called Tosya in our yard, who was working at a fish factory. She brought us huge salmons for the holidays. I remember Grandma cutting it and the caviar was slowly getting down on the board. Grandmother made the caviar herself. She also salted salmon, and boiled it. We did a thorough cleaning on Pesach eve and took away the chametz. There should not be any breadcrumbs left. Then grandmother hid a couple of slices of bread, which were supposed to be found and burned by grandfather. That was the rite.

After that we could get the Pascal dishes. Once when Grandpa was looking for bread, I took a slice of roll and threw it on the floor for Grandpa to find it easily. It was either in 1949 or 1950, several years after war. Grandfather saw that, took a thong and beat me. It was the first time in our house, and not only me, but Grandmother and Mother were shocked too. Grandfather told me, 'During the war people starved, died from hunger, how could you throw the bread on the floor?' Since that time I have never thrown away a single piece of bread, as I was so strongly impressed by Grandfather's words.

Pesach was according to tradition. Grandfather put a cap on and said the prayer. Seder started. He hid the afikoman and I was to find it with my cousins. The one who found it was given a present - either some sweets or a book. Grandfather knew all necessary prayers to be said during certain holidays.

We marked Purim and Grandmother baked a whole bunch of hamantashen. My cousins and I took shelakmones to people as per Grandmother's request. Grandfather did all that Grandmother asked him. We, kids, loved Purim. We were given masks and pageant costumes. We gave small performances and adults gave us presents for that. In general, we were pampered at Purim, we were even given wine.

On Channukah, when adults gave us money, we were not supposed to hold account how we spend it. I remember another family holiday - it was the day of the foundation of Israel 31. When Palestine was recognized as an independent state, it was such a great joy for our family! Grandmother made a feast on that occasion like on a big Jewish holiday. The whole family got together and Grandma Perelman came over. Since that time that holiday has always been marked in our family.

My grandparents lived a long life together. They were nice and friendly to each other. God sent them an easy death. Grandfather died in his sleep on 11th December 1964. Though grandmother was ten years younger, she survived him only by three months. She died on 13th March 1965. Both of them were buried in our Jewish cemetery. They had a traditional Jewish funeral.

Since childhood I was friends with my cousins, the sons of my aunt Nessie. I did not call them cousins, but brothers as they were really my blood. We were living in one apartment and always kept in touch, though I was older than them. The elder son of Aunt Nessie, Isaac was born before the war, and after the war, in 1945 my aunt gave birth to twins - Simeon and Rafael. Right after we came back from evacuation my uncle Paul, Nessie's husband, started helping Mother a lot. He raised me like his own daughter. He also bought me clothes and toys. Uncle Paul died young, in 1953. Then my parents started helping Nessie and raised her kids. It is a pity that our big family is severed.

My elder cousin, Isaac Goldman, married a Muscovite and moved to Moscow. He was a surgeon, the associate profession. His wife did not take his surname after getting married and their son got her maiden name, Kozlov, as she did not like the Jewish family name Goldman. Only when the son was to get an Estonian passport to be able to travel worldwide, he used his Father's name. Isaac's wife did not treat him fairly. She was a mean woman, money was the pivot of her life.

Isaac died from a stroke in 2003. It is good that he did not remain a cripple as it would have been terrible with the wife he had. My younger cousins are alive, though they are sick. One of them is in Düsseldorf, Germany, and the other one - in Tallinn. I often get in touch with Rafael and his family, who are living in Tallinn. He was an excellent military officer, retired with the rank of a colonel. He has a wonderful wife, Svetlana, and a son, Pavel.

When Father was released from prison, he went to work at the plant Esticable. He started working in the workshop, but not as a worker, but as a foreman. He had pyelonephritis and was sick all the time. He worked while he could stand on his feet. He was not only working at the plant, he was also elected chairman of the comrade's court in our housing administration. [Editor's note: In the USSR there were comrade's courts, consisting of the most respectable members of the team. Those courts were meant for minor delinquencies and violations of certain order or standards by the employees of the enterprise. They could make an administrative penalty: deprive people of a bonus, make a reprimand etc.]

When his consulting hours were over, people came home to see him. There was not a single time, when Father would tell anybody to make a preliminary appointment. He received people at home and helped them. There were so many people willing to see him! He was not merely loved, he was trusted. I think it is even more important than love. When Father was marking his 60th birthday, there were more than 50 people at home! Everybody found fantastic words for my father.

Then Father's diseases started progressing and he kept to bed. We were constantly looking after him, not only my mother and I, but also Nessie, her sons, and my parents' friends. Father died on 1st March 1973 at the age of 69. He was buried according to the Jewish rite in the Jewish cemetery of Tallinn. I vaguely remember his funeral. I was overcome by grief and did not see anything else. As far as I recall it was very cold and many people came. Not only Father's, but Mother's colleagues came over too. There were a lot of people, whom Father had helped, or just supported with a kind word during the hard moments of his life. Father is still remembered. Every year on Father's birthday, 24th May, I see fresh flowers on his grave. I do not know who brings them there. Once I met an unknown lady by his grave. This Estonian lady told me, 'I would have been evicted from my apartment, if your Father had not helped. Father was an amazing man and people still remember his kindness.

I went to work when I turned 16. In general, there was no need for me to drop my studies and start working. It was my wish as I wanted to become independent as soon as possible. I wanted to work and have my own money. Of course, I did not correspond to the notion of a good Jewish girl from a good Jewish family. 'Good Jewish girls' were so tacit, so proper. I was active, even a tomboy. I got transferred to the evening school after the 8th grade.

During the first year of my studies I worked as a pioneer leader at a compulsory school, but I had to quit my job: I spent a lot of time at my work, but I had to study. Then I went to the plant, where Father was working. I was the head of the warehouse of high-voltage wire. There were a lot of precious things there, costing millions. Larceny was in full swing during the Soviet times. On my first day, I held a meeting with all my subordinates and asked them not to steal as I was young, and not willing to be put behind bars only because I could be easily deceived. They loved me, did not steal and even did not swear in my presence.

Of course, the job was hard. Even now my hands get cold easily as I used to be in the freezing cold during the winter watching the wire being loaded into the cars. The containers were placed on huge trucks from which wire in huge reels was to be loaded into the cars. I counted them and recorded that in the logbook. I had to wear a huge jersey coat which was below the knees as I was short, and mitts. It was so funny - I against the background of huge stevedores. I was confident and could cope with my work. I finished evening school, when I was working at the plant then I graduated from the Librarian Department of Leningrad Culture Institute.

I went for extramural studies at the institute. I wanted to have a fully- fledged life. I worked, studied, and was involved in social activities, met my friends, fell in love - in general I managed it all. Of course, here my character also played its part, but my mother did a lot for me. She did not look after me all the time like most Jewish mothers, but she controlled me. When I was studying at an evening school, I still loathed mathematics and tried to cut the classes and suddenly my mother showed up and said where I was heading. I had to come back.

I was always surrounded by boys, I did not have many female friends. Mother always said with sadness, 'Why are those punks glued to you?' In reality, a lot of my friends were not 'good boys.' Mother never forbade me to be friends with them. In actuality, she put no bans on me, but controlled me all the time. She always told me, 'If you want to smoke, go ahead, but let me know about that. If you have friends, bring them home for me to meet them.' There were cases, when my friends came to us to talk to my mother as she also became a good friend for them.

My mom was loved by all families I knew. She was very modern and advanced, and not everybody liked that. It was the Soviet, namby-pamby time, and besides there was a special moral in Jewish families. Mother did not fit a traditional understanding of a Jewish mother and our family did not have patriarchal traditions like other families had. Mother discussed all things with them, even about intimacy. I found out about those things from her, not from my friends. I had known since childhood that I was not found in the cabbage. When I became older, it was my mother who told me that the first man should not be the husband obligatorily, but the beloved man. She also said that the experience should be in such a way that there should be no abhorrence to those relationships later. I am very grateful to my mother.

At the same time Mother was very gullible. My cousins always hoaxed her, and when it was revealed Mother was the first to laugh at a successful hoax. In a word, she took after Grandmother. Both of them were very gullible, tidy and strong. When we came back to Tallinn from evacuation I never saw my grandmother wearing a kerchief, only a hat. Mother remained stylish and elegant until her death.

Before graduation from the institute of culture I started working at the Academy of Science of Estonia. First, I worked at the library. When I got the diploma, I was named the head of the patent and license department. I worked there for many years. Then I was offered a job at the plant of the semiconductor devices named after Hans Pegelman. I had better working conditions and a higher salary there. I worked there for 20 years.

Mother worked after the war. At that time Russification started in Estonia, and the authorities decided to open a Russian drama theater in Tallinn. My mother was offered a management position there. She was supposed to do everything from scratch - find the premises, hire actors, work out the repertoire. Later on many of those actors became famous and left for Moscow, but they were starting out in our drama theater. Mother was constantly taking good care of them. First, she was an administrative manager, then the chief administrative manager.

Then she was offered a job at the traveling agency Intourist. It was very prestigious. They needed a person who was fluent in foreign languages and with good manners as she was supposed to communicate with foreign visitors, who had a different understanding of upbringing, femininity, culture, communication. Mother fit them perfectly, though she was 70 years old. She was fluent in German, Finnish and English, but still she had to take exams in those languages at the Tallinn Teachers' Training Institute. Of course, it was a mere formality, as everybody understood that she had good language skills. She passed the exams and was offered the position of the chief administrative manager at Intourist.

When the first and only variety show in the Soviet Union, Astoria, was opened in Estonia, Mother was offered to be in charge. She took to business. It was not hard only because she had to start from scratch. At that time bribes were not legal, but nobody struggled against them, and they were deemed natural. Of course, there were very many people who wanted to see the variety show and everybody tried making money on that, starting from the ushers who let people in. At that time each Astoria usher had two to three cars.

Mother never took bribes. Those who did not know that and offered her money had to listen to many unpleasant words from her. In general, Mother always stuck to one rule: expensive presents could be accepted only from close people, as for the others - only flours and sweets - a natural way to pay heed to a lady. Mother never made any exceptions to that rule when she was working for the variety show.

In general, Mother always remained a big child - naive, honest and kind. Here is an example: once the captain of the whale boat Slava came over. It was hard to get in and he said that he had come to Tallinn only to see Astoria. Mother gave him a table. Then, when she was walking by, she saw that he was drunk and his wallet was popping out of his jacket, and could be easily stolen. Mother took his money and put it in the safe. Next day she called the hotel and told him to come and get his money. She had saved his income of six months.

Only those people who knew Mother very well could believe that she did it without self-interest. She found it natural to help people. Besides, she was very demanding and strict and all waiters obeyed her. Nobody could rebuke her as she was independent - she never took money from anybody, made no benefits for herself. She brought her own sandwiches and tea in a flask to work. She thought she can demand honesty from somebody only if she is honest herself. Mother worked in Astoria as long as she could do so physically.

After 85 she had a cataract and she started getting blind. Then she left her work. Since that time she lived with me. Unfortunately, it was not her only trouble. Several years later, she fell and broke her femoral neck. The doctors refused operating on her as they were afraid that she would not survive it. She was almost 90. She could not walk.

My husband and I tried to do our best for her not to suffer from loneliness. Both of us worked and the sitter was with her all the time. I often called Mother from work. I spent my spare time with her. When our friends came over, they went to see Mom. She had always remained the favorite. She died in summer 2005. She was buried in our Jewish cemetery according to the Jewish rite. Her grave is by Father's. There were a lot of people at her funeral, I even did not know some of them. They said she was a unique person, a legend. They said the whole epoch is gone with her. Probably, those were not merely beautiful words.

In 1968 I was offered to join the Party. It was considered to be a big honor and it would be easier to get promoted with that. I came home and told Father about it. Then my father, he was very rarely sharp, said to me, that he would not explain anything, but I had to make a choice: either I join the Party and forget about my parents, or refuse joining the Party. Then he said that I would understand it one day. Of course, I did not join the Party and was very grateful to Father for that.

I was married twice, and both of my husbands were Estonians. Maybe my parents were not happy with the fact that I did not marry a Jew, but they respected my choice. I know that there are some Jewish families in Tallinn, who treat marriage with a non-Jew like a breach of peace and are strongly against such marriages. It also happened among the intelligentsia. It was not like that in our family. Probably, it is not a very nice thing to say, but I love Jewish men as friends, interlocutors, but if it comes to doing some things about the house, it turns out that they have two left hands. Of course, it is possible to call the locksmith and sanitary technician, but I like it when some small repairs are done by my husband.

I do not know if my first husband would be pleased if I talk about him, so I will just say a few words. I kept his last name Laud even after the divorce. He was a very nice man and we remained friends. Love was gone.... My first husband was a scientist, he 'built castles in sky,' but I had to stand with both feet on the ground. We were absolutely different, but when we were young, we thought that we would accomplish each other, but then it turned out that it was hard for us to live together.

In 1986 I got married for the second time. My husband, Rein Plaado, is wonderful. At that time my father was no longer alive. Mother liked Rein a lot. We lived together in civil marriage for ten years and then he talked me into having our marriage registered. I kept my name as I had a permit to restricted documents at work, so I did not want that hassle with processing it once again.

My husband, Rein Plaado, was born in Tartu 1942. I am four years older than him, and I hope it is not noticeable. Rein was the middle brother. His elder brother is still alive and the younger one is dead. Rein was sorry that his mother never got a chance to meet me; she died young, at the age of 48. I am also sorry for that as he always says nice things about his mother, even if it makes me cry. Rein was the only good son of hers, as the younger and the elder ones drank. He was the only of her children who had a higher education. Rein graduated from Tallinn Polytechnic Institute. He is a chemical engineer. Now he is the director of company Plastronic, dealing with plasmas.

To put it briefly, he is probably the only man who can bear such an authoritarian woman like me. I think we have a lot in common: we like the same pictures, books. Another important thing is that he has a good sense of humor. Rein always recognizes the right of other people to live as they wish and that is also important for me. He was well educated. There was not a single time when I was ashamed of him.

We have been together for 19 years. It is Rein's second marriage. He has two children in his first marriage: a son and a daughter. They are adults now. They are living in Tartu, but visit us. I do not have children, neither from the first nor from the second marriage. I could have had children, but I refused. During the Soviet time I could not leave my job and raise children, and have them looked after by Mother once a week and spend the rest of the time in a kindergarten or at extra curriculum classes at school.

My mother adored Rein. Once she said if all Jewish sons were like Rein, there would be more happy mothers. Rein loved my mother very much and I am grateful for that. He also pampered her, bought her flowers and presents. When Mother could not walk, he looked after her like a devoted son. He carried her into the bathroom in his arms, took her for walks. He often talked to her. When he came back from work, he went to her and shared all things with her that had happened during the day. He called her mommy and 'My Baroness!'

Even after the war Estonia was much different from Soviet republics. My friends from Azerbaijan called it 'a piece of Europe in the Soviet Union.' The Soviet regime differed in Estonia as key positions were taken by Estonians. Of course, those at power were supposed to fulfill the orders of Moscow, but they tried to soften it and make it less burdensome for the people. In general, Estonia was always a liberal country and it helped them in resisting forced Russification and Soviet ideology.

There was no state anti-Semitism during the Soviet regime in Estonia. Due to that there was a bright pleiad of world-known academicians and scientists in Estonia. Jewish scientists were turned out of Moscow and Leningrad universities during the campaign against cosmopolitans and the Doctors' Plot. Many of them came to Estonia, and they were gladly accepted at Tartu University. There were Yuri Lotman 32, the academicians Bronstein, Blum and others, whom Estonia was proud of.

Even when anti-Semitism was in a full swing, Jews could get higher education here. Students from all over the Soviet Union came here to enter the institutions of higher education as they knew perfectly well that here their knowledge would be estimated, rather than the information in the forms. In everyday life the Estonian population liked the Jews. They knew if they needed some help - they would better consult a Jewish doctor and lawyer.

We always followed the events in Israel. It was much easier in Estonia than for the rest of the citizens of the USSR as since 1962 we had a chance to watch Finnish television. It was unofficial, but not banned. Finnish television was a door to the world. There were programs in German and English with subtitles in English. Our entire family knew those languages. Finnish television broadcast a lot of newsreels about Israel. I remember the series of programs called 'Historic Palestine.' They showed the first Jewish settlers there and what they built in Israel.

When there were wars in Israel, the Six-Day-War 33 and the Yom Kippur War 34, there were Finish radio and television broadcasts every day. I was working at the Academy of Science at that time, at a special design bureau. I was in charge of the patent and license department. I had a separate office. There was a large map of Israel on the wall. Every day my colleague Eric Uzhvanskiy and I marked the battles and victories of Israel on that map. There were mostly Estonians in my team and only a few Jews. Even Estonian were worried about Israel!

From early morning they were listening to Finnish radio and then rushed into my office exclaiming with joy, 'Cilja, they won again!' and waited for me to put another mark on my map. Estonians sympathized with the Israelis. It was strange, but true. They have always been liberal and always were worried for a small country that fought for its freedom. I remember, once an elderly academician, Eifeld, an Estonian, a bright representative of the intelligentsia came to me and said, 'I understand that.' Then added, 'You, Jews, are an amazingly talented nation.' Such recognition means a lot! At home, Father also followed military actions. Every Israeli victory was a joy for him, his personal victory.

When there appeared a chance to leave for Israel, many of our friends and pals immigrated. We even did not discuss such an opportunity at home. My parents said that there was too much of an Orient in Israel, and added that they were used to live here. We were used to Estonian reticence, and even aloofness. Our assimilation is not the reason for it. We have always been Jews, in Soviet and post-Soviet times, but we felt that we were residents of Estonia.

When perestroika 35 started in the USSR, it was not as conspicuous and important for Estonia as for other republics. I have already mentioned that Estonia was the most non-Soviet out of all Soviet republics as we had much more opportunities than other republics. We were almost unrestricted in informational freedom and the Iron Curtain 36 was not as heavy here. During the Soviet times, Estonians had a chance to go abroad, and it was much easier for them than for others. There were a lot of trip vouchers, and it was easy to get them. It was common to go to Finland and many people went there.

The only restriction was for those who were working with top secret documents, like me, but there were very few of them. There was also freedom of speech, maybe not like now, but still it was incomparable with Russia. People could speak openly without having fear of informers. When I came to Moscow to see my aunt Katerina, we started whispering during a discussion of politics so that the neighbors would not hear us. Nothing of the kind happened here. Estonian are really honest and amazingly hardworking people.

In 1987 I left the plant and was employed at the National Library of Estonia. There were only two non-Estonians among the employees of the library: a Jew, Regina Pats, who is still working there, a very nice person with broken Estonian, and I. 680 Estonians elected me the chairman of the trade union committee. It was a funny time, the last years of perestroika. There shelves in the store were empty - no things, no products. I was an old fox with an adventurous spirit, so I found a way to get things, and if needed I bribed people. We reached an agreement with the Tallinn shoe factory and they sold shoes in our factory. They brought us a whole bunch of frozen chicken from the grocery base. It was such great luck at that time. We were given trip vouchers, bikes and TV-sets. All our employees got good food and clothes. It was not the only thing I did. In summer our team went for picnics. I arranged a choir there. In general, I tried to make life better for people.

When I reached the age of 55, the pension age in the USSR, I quit my job. At that time the Jewish community of Estonia was open and its chairman, Gennadiy Gramberg, invited me to work there. My colleagues did not want me to leave, tried to talk me into staying, but my decision was firm. I have always been a true Jew. Blood is thicker than water. I am proud of being a Jew, and do not want to be anything else. I went to work at the community when it was just budding.

The Jewish community of Estonia was the first Jewish community in the Soviet Union. In late 1988, during the Soviet regime, it was open in the form of the Jewish Culture Society. It was founded under permission of the Department of Ancient Historical Memoranda Protection, as during the Soviet times the national minorities were handled by that department. Trime Veliste was the director of Ancient Historical Memoranda Protection. Now he is an ardent nationalist, in the bad sense of the word. Nevertheless, he personally approved of the foundation of the Jewish Culture Community. He gave us underground facilities at Vene Street.

The Tallinn Jews David Slomka, Gidon Paeson, Samuel Lazikin were the founders of the community. It existed until 1990 and since then the Jewish religious community held a meeting at the plant of semiconductor devices, where I had worked for 20 years. There it was decided to rename the Jewish Culture Community into Jewish Community of Estonia. Thus it has existed since 1990. They gave us the old premises of the Jewish lyceum 37. The community repaired it and since then we have had our own building. Besides, we opened a Jewish school there and in 2000 the synagogue was opened.

Before Estonia became Soviet in 1940, we had a female Jewish Zionist organization - WIZO 38. It was very active in Estonian times. In 1990 we revived it and I was the one who took care of that. In 1989 the Jewish organization of Sweden invited me to come over. A very famous Zionist, the founder of the Swedish WIZO, Charlotte Etlinger, was living in Sweden at that time. I met her when I was in Stockholm. We spoke in Yiddish. She was trying to convince me that I should revive WIZO in Estonia, go to Israel and see with my own eyes how WIZO is working to understand the goals and tasks and the way to tackle them.

Life was hard in Estonia at that time, and I did not have money for that trip. When my sick Aunt Nessie found out about that trip, she gave me money for that, $100, bought me the ticket to Israel and talked me into going there. When I returned from Israel, I founded WIZO in our community and was its president for 4 years. WIZO is still active, but unfortunately it is not the way it was from the very beginning. Earlier there were a lot of young ladies, the enthusiasts, who used to be very active. We had to start from scratch. The motto of WIZO in Estonia as well as in many other countries of the world is as follows: strong Diaspora - strong Israel.

The main task of WIZO is propaganda of the Zionistic movement as the liberation movement for Jewish peoples. In other words: get out of slavery and become a fully-fledged citizen of Israel. And the second goal is the flourishing of Israel. Many WIZO ladies from all over the world collected money for our state. Houses, kindergartens, hospitals were built in Israel on that money as life there is like a powder keg. We could not collect money for Israel in Estonia as we merely did not have money. We mostly dealt with propaganda of the liberation movement.

Many Jews who came to Estonia after the war did not know anything about it, as in Soviet time Zionism was equal to fascism. Of course, it was important to explain what it was. WIZO held lectures about renowned activists of Jewish culture, science, the liberation Zionist movement. We helped the sick ones, came to see them in the hospitals, brought products to old people, congratulated them on holidays, brought humanitarian help and gave them to people for free. We did our best. I had been the president of WIZO for four years when I was elected the chairwoman of the Jewish community of Estonia.

At the beginning of the occupation of Tallinn by fascists, the Tallinn rabbi Aba Gomer 39 was murdered. In 1944 the Germans burned our wonderful synagogue in gothic style at the corner of ?akri and ?ante Street. It burned down during the bombing of Tallinn. Since that time there was neither a decent synagogue nor rabbi in Tallinn. Those people who were acting as rabbis, had no education. One of them was a gabbai, the religious warden of the synagogue.