Dr. Janos Gottlieb

Iaşi

Romania

Interviewer: Emoke Major

Date of interview: October 2006

My meeting with dr. Janos Gottlieb impressed me a lot – I spent a very interesting time with him in his apartment in Iasi, in a family house, which though situated in the center, is in a quiet area, where he lives with his wife.

Their apartment is homely; the way it is furnished speaks of educated occupants with a lot of books, works of art and a systematic disorder of his table characteristic of men of science.

So we had a pleasant environment, but the intimate, warm atmosphere was ensured mainly by the informal, friendly, helpful, merry personality of Janos Gottlieb.

I was charmed most of all by the spiritual splendor, love of life and cheerfulness typical of him, which is the somewhat paradox, though perhaps natural privilege of people who have known hell from close.

- My family background

Both my father and my mother are from Maramarossziget. Besides – I found this out subsequently from Pal Sandor, my father’s half-brother – my father was a kohen, so he came from a relatively religious Jewish family, but he wasn’t religious. I’m not religious either. But that’s not the point.

In fact my father’s father, also a Gottlieb got to Maramarossziget from Austria. In those times the Austrian-Hungarian k. u. k. army 1 still existed, and that’s how he got to Maramarossziget, but I ignore precisely when. My father was born in 1897 in Maramarossziget. He didn’t know his father, who had died at a very young age. My father was a few months old when his father died.

So he didn’t know much about his father’s life either. Perhaps I have his name noted down somewhere, but I don’t know it by heart. However, we didn’t ever talk about him, we used to talk only about uncle Gottlieb. My father’s father had a brother, who was a colonel in the k. u. k. army, though he was a Jew, which was a great deal. This uncle of my father was called Lajos Gottlieb.

He considered himself such a Hungarian, and such a devoted k. u. k. colonel [Editor’s note: k. u. k. = kaiserlich und konigh, which stands for imperial and royal], that when in 1919, when the Bela Kun revolution 2 broke out, and his stripes were torn off, he went home and died of a heart attack.

My father used to speak of him nicely. He said his uncle was a man of principle, and in fact it was him who had supported my father. I’ve already told you that my father was orphan, my grandmother got married again, and she had two more children, so she couldn’t help him much, but his uncle did. In short he spoke of him nicely, he said him to be an honest, high-ranking officer – well, a colonel in fact.

[Editor’s note: According to a document to be found in the National Archives of Hungary ex-colonel Lajos Gottlieb was given the title of nobility in February 1918 (www.arcanum.hu/mol/lpext.dll/MT/918/91d?fn=document-frame.htm&f=templates&2.0 - 15k)]. He lived somewhere in Hungary, but I don’t know where. Thus both grandfather Gottlieb and his brother came from the Austrian part to Hungary, respectively to the Maramaros region. That was it from the side of my father’s father.

My paternal grandmother was called Szeren Klein. There was a village-like settlement near Maramarossziget, it is called Szigetkamara [in Romanian Camara Sighet], it belongs to Maramarossziget, and my grandmother was born there. She came from a relatively good family, I knew two brothers of her from Maramarossziget.

Unluckily one of them fell into depravity, because he wanted to become an actor, and his family didn’t let him. Thus he became a little… In turn the other was a lawyer in Maramarossziget; Artur Klein was a famous lawyer. They came from a good family, I knew both Artur Klein and her other brother.

Artur Klein had one son, who died during World War II, the other had a daughter, who didn’t come home from deportation, and a son, who came home from work service – he was called Istvan Klein, he was called Klein like my grandmother. I met Istvan Klein in Kolozsvar after the war; I have to tell you what happened to him.

He was older than me, and he was doing work service. When his unit was retreating, he managed to detach himself from his companions and hid away. The Soviet troops were following them; he waited them with open arms, but the Russians caught him and took him to Russia to work in a prison 3.

So one could speak to him about socialism endlessly, he couldn’t be convinced about how good the Soviet system was. He came back; I met him in Kolozsvar after a few years, I was already a student, and his dream was to leave Romania. He managed to do so. Finally he lived in Bogota, in Colombia until his death. He isn’t alive either. He didn’t have any children.

Both brothers of grandmother Klein lived in Maramarossziget, and they died either in Maramarossziget, either in deportation. They were already old, if they were taken to Auschwitz, they must have died there. Artur Klein wasn’t much religious; I didn’t get to know the other well.

Once I stayed at Artur Klein in Maramarossziget, so I know: he wasn’t religious. You know how it is: Jews do observe certain high days, but that doesn’t mean they are religious. My father went to the synagogue too, let’s say on Rosh Hashanah or on Yom Kippur, and he took me with him, we had conversations there with the acquaintances – this was the high day. Well, this doesn’t mean we lived a religious life.

Grandmother Klein was my beloved grandmother; she was a divine creature. My father was left orphan, and my grandmother got married again. Her second husband is known as Sandor, Arnold Sandor. Originally his name was Stern, but he changed it 4. He had a brother in Budapest – I never met him –, he was also Stern, but he became Csillag.

My grandmother’s family spoke Hungarian, at least everybody spoke Hungarian with me. Grandma was very religious. She didn’t have a wig, she wasn’t that religious, but she was very religious, she ate only kosher and so on. Not my grandfather, he liked bacon, and he had to keep it between the window-frames, he wasn’t allowed to take it into the house.

Grandfather Sandor was a bank manager, he was getting a pension, he had means to live on, he didn’t have problems. He wasn’t a bank manager in Maramarossziget, but somewhere else, I don’t know precisely where; however he was from Maramarossziget, and he went back there. When both of them retired, my father took them to Nagybanya, they had an apartment and lived there.

With Arnold Sandor, grandma’s second husband – whom I loved a lot as well – my grandmother had two children: Pal Sandor and Erzsebet Sandor, who were ten, respectively thirteen years younger than my father.

Pal Sandor was the elder; he was born in 1907 in Maramarossziget. They lived in Bucharest. His wife was called Angela Rosenthal – we called her Angi –, she was from Temesvar. My uncle’s wife was an extremely intelligent woman, and they had an outstandingly wonderful family life.

I stayed at them in Bucharest sometimes even for weeks, and I saw them quarreling once – on who should do the dishes. Everybody wanted to do the dishes. It’s really funny… First my uncle was a clerk, then he became a journalist at a Hungarian newspaper, at the ‘Szakszervezeti Elet’ [Trade Union Life].

This was the Hungarian edition of the ‘Viata Sindicala’, in those times it was published in Hungarian as well. My aunt did the same: she was a clerk, then a journalist at the ‘Romaniai Magyar Szo’ [Paper of Hungarians from Romania] – back then it was called ‘Elore’.

My uncle left for Israel at the age of almost eighty years – when his daughter, Eva moved to France – together with his wife, because it would have been quite difficult to stay in touch with his daughter during the Ceausescu era. So he left for Israel quite late, and he died there in 1997, he was almost ninety.

They had their sixty-fifth wedding anniversary a few days before my uncle’s death. He always meant an example for me, they had a very nice marital life. My aunt loved her husband very much; she didn’t live much after his death. We talked quite often on the phone, and I saw them too, because in 1992 I was in Israel; both were still alive.

I knew her husband was very ill. She said if Pali died, she would hang herself up. In short she loved him very much. She didn’t hang herself up, but she died soon after his death, she didn’t live much after. She wasn’t much younger than him, there was a difference of age of five years between them.

Their daughter, Eva Sandor was born in April 1940. Her name is Barbulescu after her husband. Her husband is Christian, he was a lecturer or associate professor, something like that at the Faculty of Chemistry of the Technical University in Bucharest. Eva was a physicist.

She studied here, in Iasi – I brought her here, I was already a lecturer at the University of Iasi. After she finished the university, she went back to Bucharest, and she was employed as a researcher by different institutions. Later she took her doctorate in physics in Bucharest.

Of course she’s retired too by now in France, because she defected to France with her husband a few years before Ceausescu’s fall 5. They have two children, who were born here, in Romania, so they left the country together. The children were quite grown-up, when they emigrated.

I’ve mentioned that her husband was called Barbulescu, the children have Romanian first names. The boy is Virgil, his sister is Irina. Irina got married there to a French man, Virgil got married this summer [in 2007].

Erzsebet Sandor was called Bozsi within the family; she was born in 1910 in Maramarossziget. She lived in Temesvar, she got married to Lajos Lobl, and she took over his name, so she wasn’t called Erzsebet Sandor, but Erzsebet Lobl. While she lived in Temesvar, she worked as a secretary; she was a very pretty woman, she was gorgeously beautiful.

I loved her very much. And she could also sing very nicely. She was such a great singer that she even had concerts in Temesvar. I don’t know what Lajos Lobl was engaged here in Romania; I was ten when they left for Palestine – I know the date when they emigrated, because I was born in 1929, and they left in 1939 –, they were great patriots 6. In turn I do know what they were doing there: they opened a photographic studio.

There was a time when Erzsebet was a news announcer at the Hungarian edition of the Kol Israel radio station – I listened to her here, in Romania after World War II, in the 1950s of course. They lived in Tel Aviv. I don’t know precisely in which year she died, however, she died at quite a young age, much younger that her elder brother, Sandor, who was two years older than her, and was almost ninety when he died.

I don’t remember the year for sure; in any case I already lived in Iasi, when Bozsi [Erzsebet] Lobl died. When I got married for the second time in 1962, she wasn’t alive anymore. Thus she died at the beginning of the 1960s at the age of fifty and something. She didn’t have any children.

Nobody was religious, neither Pal Sandor, neither Erzsebet Sandor. Not at all. Not only that Erzsebet Sandor wasn’t religious, moreover she was a nationalist.

My father was called Laszlo Gottlieb, he was called Laci within the family. His Romanian name in the Romanian era – after 1920 – was Vasile. He was born in 1897 in Maramarossziget. After my father finished high school, he got to Budapest. He studied for one year there, at the Technical University.

World War I broke out, therefore he interrupted his studies, and he was enrolled directly into the Military Academy, because he was a university student. He was an under-lieutenant, then a lieutenant. He fought during the entire World War I, he was on the Italian front line, then on the Russian front line as well, on both front lines; he had four decorations, one of them was the Iron Cross.

I will tell you why this was important: he considered himself to be a real Hungarian person. I’m telling you this now, because I was with him in the concentration camp.

They destroyed him in his spirit. Considering what a great Hungarian he considered himself, what decorations he was given from the Hungarian army, the k. u. k. army, after all this to be taken to a concentration camp, this was too much for him. So he broke down mainly mentally. That’s why I’ve told you all this.

After World War I he didn’t pursue his studies anymore, he got back to Maramarossziget, he hid for a short period, when Bela Kun failed, because he was leftist. He ceased to be a leftist quite shortly, so he didn’t become an extreme leftist. Later he got to realize what all this was about, but this happened in subsequent years.

And I also know about him that he was member to the Galileo Circle, which was in fact a leftist circle. The Galileo Circle was established in Budapest. I think it worked through the university, perhaps within the technical university. At the time of the Bela Kun revolution of 1919 he was an officer, and he joined the revolution as an officer.

I know this for sure. And when Bela Kun fell, my father went home to his mother, who lived in Szigetkamaras, near Maramarossziget, and he didn’t leave the house in daytime for many months. He was afraid of being searched for, of getting arrested.

Especially that he joined the revolution as an officer, this was a significant detail. All this happened when his uncle, Lajos Gottlieb got a heart attack, for he was so grieved about the fact that he was downgraded.

I’ve already mentioned that my father was disappointed in the left wing. Why this? He read a lot. He listened to the radio a lot. He spoke a very good English – unfortunately I don’t speak English so well –, and he listened to the BBC a lot. And sooner or later – before others did – he found out what Stalin was doing in the Soviet Union. From the BBC, from other sources. Well, television didn’t exist yet, this was in the 1930s. I don’t know exactly what was what he knew, because he was afraid to talk about this with me – I was still a child, I wasn’t even ten years old. However, I could see he was disappointed, though he flirted with the left wing. For example there were people visiting us, who were leftists, and they were arrested as underground communists; my father withdrew with them, they were talking, but without me. As far as I know, my father didn’t take part in the International Red Aid, but he supported the leftist movement. But in secret.

He tried to explain to me why he disliked communism. It was something odd that according to communism every person is alike and is judged equally, which was not convenient for him, because he learnt much more and knew much more than, let’s say, a simple worker. Why should he be alike the worker? In brief, he tried to explain this to me.

The result of this was that up to 1947 I had not even the slightest intention to become a party member. Now we make a detour to the postwar period… What happened in 1947? I was eighteen and a half years old, almost nineteen, when I went to study to Kolozsvar.

We had a very good acquaintance in Kolozsvar, I will tell you his name too, doctor Arpad Kis, a pediatrician; we had been together in the concentration camp. He was Jewish as well, in fact his name was Klein, he changed this name into Kis. We were together in the concentration camp; he had the luck to survive; it is something very rare: his wife survived as well, and they met in Germany soon after liberation in a miraculous way.

Both of them came home, but their child – they had a daughter, Agnes – didn’t come home. Agnes was born in the same year as me, and I was the kid they accepted in their family – even though they had one more child after the war. True that at an advanced age, but they managed to have one more child, he’s in Israel, I know nothing about him. Peter Kis, he’s a historian, that’s all I know about him.

During the illegal communist movement Arpad Kis was the physician of the International Red Aid in Kolozsvar. He was a doctor, he had a house, he had his own office and everything, yet he was the Red Aid’s physician.

When I got into the family of Arpad Kis in 1947, and I told him I wasn’t a party member, he said: ‘You have to join the party.’ He had me entered into the party. It wasn’t me who entered. However it turned out to be a relatively good thing, because later I realized that this made my academic career much easier. So sometimes I say as a joke that I became a party member out of conviction: I was convinced this would be useful to me. This was my conviction.

I know though that after I came home from deportation, I was still in Nagybanya, and there was an illegal communist there, a very likeable man, Jozsef Hutira, we called him Joska Hutira. He was much older than me, but we became friends, and I loved him very much, because he was a very straight character in fact.

His elder brother, Dezso Hutira, whom I didn’t get to know, was executed as an illegal communist. After World War II they established a factory in Nagybanya – I don’t know what kind of factory, all I know is that there was a factory –, which was called Dezso Hutira. He became a hero. When I got back to Nagybanya, Joska Hutira helped me, and he told everybody that I was the son of Laszlo Gottlieb, who had supported the leftist movement.

But he never told me about any actual deed of my father, so I ignore what my father had done exactly. So I rather found out things indirectly than directly.

Joska Hutira was known in Nagybanya and in Bucharest too. He had had different assignments as an illegal communist, but after World War II he got into the Militia, the police, and he was a high-ranked officer in Bucharest, at the DGM, that is the Directia Generala a Militiei [General Department of the Militia].

Later he got to Kolozsvar, and he was the police superintendent of the Kolozsvar territory. The first thing he did under his appointment was that he fired a thousand militia-men, either because they were drinking, either because of other offences – he fired them at once. This happened at the end of the 1940s, or at the beginning of the 1950s.

The maiden name of my mother was Zelmanovits; she was from Maramarossziget as well. Her father died during World War I, so I didn’t get to know him. But my grandmother survived, and I visited her sometimes in Maramarossziget – she was living there –, my father took me to her too.

People called her auntie Zelmanovits, I don’t know her first name, I never used it. She had a house, a garden and a stable, she was living on these, because neighbor peasants used to leave their horse or cow at hers. They paid her for this, so this was her source for living. She lived on her house. This was my grandmother’s occupation.

Well, the truth is that I loved very much my paternal grandmother, and I loved less my maternal grandmother. She loved me very much, I admit it, well, I was the only one from my mother’s family, who stayed in Romania after my mother’s death, and whom she saw sometimes, because the other members of the family – her son and his family – were in Czechoslovakia.

However, how should I put this, she never became a really likeable person for me. I don’t know why. Though the poor creature tried to become, but… it simply didn’t work.

That’s it, we all feel sympathy and aversion too. She wasn’t repugnant, I would not say so, but she wasn’t that person whom… I loved the other very much. I had a totally different relationship with her, I ignore why. Though when I visited her, my poor grandmother took me to the circus, took me everywhere to make me feel good at hers. I could hardly wait those few days or the week to be up, while I was there, and I was impatient to go back to Nagybanya.

I think grandmother Zelmanovits died in 1941 because of a heart disease. She was around eighty-two. So she wasn’t deported. People used to say what a fortunate thing it was that she died before deportation.

My maternal grandmother had a son – so my mother had a brother – who was a lawyer in Beregszasz – that is Berehove, it belonged to the Czechs. [Editor’s note: Today Beregszasz is in Ukraine.] He died in Beregszasz before deportation – this was his luck.

He had two children, a son – Bela Zelmanovits, I knew him well – and a daughter – I didn’t know her well, she died during World War II. The boy survived World War II, but he died at quite a young age because of a heart disease in Czechoslovakia. And this was all about this part of the family.

My mother was called Rozsi Zelmanovits, Rozalia, I don’t know for sure how her name was entered in the ID. My mother died when I was five years old, so I have only a very few memories of her. She played the piano well, I remember this.

She was a nice woman, I have a photo of her. One thing is sure, I met people who had known her, everybody loved her as well as they liked my father. I don’t know much about her. Well, I was five when she died. And not only that I was five, I have to tell you one more thing.

When I was three years old, I didn’t live with her anymore, but at my paternal grandparents, because my mother had tuberculosis, so they took me away from her to avoid that I got the disease. Finally my mother died in 1934.

So in 1919 my father went back to Maramarossziget, he fell in love with my mother, and married her. They moved to Nagybanya together in 1926 or in 1927, because there were better possibilities of employment. My father became one of the main clerks of the famous Phonix Factory, which was mainly a sulfuric acid factory.

He worked there until World War II, until deportation. He had had a job in Maramarossziget too, but I don’t know exactly what kind of job. The Phonix Factory had three owners: Artur Weiser, his brother called Oszkar Weiser and one more person, but in fact it was Artur Weiser who managed the factory. He was an extremely good manager.

My father worked for him as a highly positioned employee, but in fact the manager summoned him many times as a private secretary and asked for his advice. Artur Weiser wasn’t married; he survived World War II, he lived in Bucharest, he didn’t have any money, and he died there at an advanced age, he almost starved to death.

I don’t know what became of Oszkar Weiser. Miklos Weiser was the son of Oszkar Weiser, he supported me in the period following World War II. [Editor’s note: ‘In 1909 the Weiser family leased for several decades the sulfuric acid factory of Fernezely.

That’s how the Fonix factory was established, which was later moved to Nagybanya, in the place of the glassworks which had failed. They enlarged it with newly bought lots. In the meantime the family became the owner of the lead and zinc mine of Herzsa, thus they gave up chemistry, the production of sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, copper sulfate etc., and started to process lead and silver. Following the Second Vienna Dictate the Phonix Factory was merged into the Hungaria Chemistry Factory.’ (www.nagybanya.ro/vallas-type-5.htm)]

- Growing up

I, Janos Gottlieb was born in 1929 in Nagybanya. From the age of three I lived at my paternal grandparents. My grandparents lived in a village somewhere near Nagybanya for a while, I was with them there too, then in Nagybanya. But when I was five years old, my father took me with him, he rented a quite nice apartment, in a nice part, let’s say, of Nagybanya, in a villa.

The owner was a woman from Kolozsvar, a widow, her family name was Herczeg. The rent was quite high, but it was in the outskirts, the air was fine there. My father always feared that I got tuberculosis or something like that. This was when I was five.

We had somebody who did the housekeeping; my father had a good salary, in those times this didn’t mean a problem. Later it was my step-mother who did the housekeeping. Well, it wasn’t her who actually worked, but she gave out the tasks for everybody. It wasn’t her who did the cooking, we had a cook. This wasn’t a problem.

It was something extraordinary that in the neighboring villa a dentist lived, who was called Kalman Gottlieb. He wasn’t our relative though. Due to an accident or maybe to an illness Kalman Gottlieb became immobilized, he couldn’t walk, so he brought there his niece – so his brother’s daughter – to have her there to help him.

That’s how it happened that when I was seven years old – approximately in 1936 or 1937 – my father got married for the second time, he married this lady. I already knew her, Lili Garai, and we were on good terms. Interesting enough that she was called Garai, because her father changed his name from Gottlieb to Garai.

But in fact they weren’t our relatives. Grandfather Gottlieb, who became Garai, lived in Deva. So my mom, my second mom came to Nagybanya from Deva. I didn’t keep the contact with grandparents Gottlieb, but I visited them once, since they survived World War II. [Editor’s note: For they lived in South-Transylvania, which belonged to Romania during World War II.] 7 I knew them before the war already. I don’t know their first names anymore. I called them grandma and grandpa.

What can I say about my second mom? First thing is that her great merit was that she was fifteen years younger than my father. She was a clever woman, she finished high school, she didn’t pursue her studies, but this wasn’t a problem at that time. She finished high school, and she was reading a lot, so she was educated, one could have a talk with her.

She was very kind to me, but she wasn’t a mother after all. She didn’t survive the war either, but she had two elder brothers. One of them, Janos Garai didn’t have any children. They lived in Deva, later they made aliyah to Israel. Janos Garai died recently in Israel, but his widow still lives in Israel, and we are on good terms, I’m in contact with her.

The other brother, Sandor Garai had a son in Italy. Sandor Garai studied in Italy, and he took up with a lady who lived in the same house with him, and they had a child. They never get married, but he recognized the child, he’s called Garai even today, he’s catholic, he lives in Bologna. Giorgio Garai, in Bologna. I visited him once.

I said, well, we are cousins after all – there isn’t any blood relationship between us, but we are cousins. Life is complicated. He’s a very nice person. He doesn’t speak Hungarian at all. We talk in English, my wife talks in Italian to him, because she speaks Italian. I don’t speak Italian, but Giorgio speaks some English, so we could understand each other, that’s what it matters. He had a wholesale business, he was selling building components, that was his occupation. He’s an old man too by now, he retired. He has four children.

I have learnt many things from my father, for example I enjoy reading even today. My father was a very apt character, and he was always on learning and reading. He was reading a lot of literature, but he liked reading scientific books and periodicals as well. He subscribed to scientific periodicals, we had the ‘Elet es Tudomany’ [Life and Science] in Hungarian edition – it had a different content than the Romanian edition.

Concerning newspapers he was reading the ‘Brassoi Lapok’, in those times they were distributing it in Nagybanya as well. But now we talk mainly about books. He had a very good collection, he had a great amount of books, encyclopedias and other books too, all kinds of books.

He was reading a lot; he was an extremely educated person. He was much more educated than me. This has a reason. For when I started to learn mathematics, I didn’t have much time left to read other things. I was reading, but not so much.

So my father was a self-educated man. And he knew many things. He learnt to speak English well, he learnt mineralogy. He made two nice collections of minerals, one for him, and one for the owners of the Phonix Factory. These were scientific collections, for it was written there everything, the name of the mineral, where and when it was found and so on.

Concerning minerals the thing is that when the miners advance in the stulm, and find a quarry of minerals, they sometimes find a piece of mineral which is beautiful in the middle. They take out those stones and steal them. This is the truth. Nobody looked after them, they weren’t bothered – this was their extra source of income.

Sometimes I went with my father in the homes of miners, they had minerals, he negotiated with them, and he bought the quartzes there, he didn’t actually go to the mine for them. It was also the miners who informed him about the place and date of the finding, and my father noted instantly these details.

That’s how he made his quartz collection. [Editor’s note: ‘Quartz is a mineral to be found underground and made up of one or more minerals. It has special aesthetic features due to the intergrowth, color, shape of adjacent minerals, and of the particular dimension of constituent crystals.’ (http://www.museum.hu/museum/archive_temp_hu.php?ID=374) One of the most beautiful quartz museums of Europe can be found in Nagybanya.] My father was an extremely intelligent and kind man, people loved him a lot.

The workers up to the director – everybody liked him. Just to tell you one thing: I was already living here, in Iasi, so a long time after the war, when the university of Iasi organized an excursion for the students to Nagybanya, and they wanted to visit the Phonix Factory.

I was in the group as well – I was already a teacher –, and I went to the Phonix Factory to discuss with them, after all my father was an employee there. The workers’ leader used to be a worker back then. When he found out I was the son of Laszlo Gottlieb, all the doors were open at once. They loved him so much. Everybody loved him.

I inherited from my mother my liking for music. If I can, I listen to music all day. Classical music, not just any kind of music. After my mother’s death I took piano lessons too. We had a piano at home, and I enjoyed playing the piano, but I didn’t want this to be my profession. I have a cottage piano even today.

In fact I didn’t get any particular Jewish education, I received a rather Hungarian education at home as well. I didn’t learn to speak Hebrew, I don’t speak at all. Unfortunately. It’s a good thing to know one more language, but that was it. A visiting teacher taught me to read in Hebrew, but I never understood what I was reading. He used to come to us when I was around eight years old until I became twelve, for three or four years, but only once in a week.

I can tell only a few things about the Jewish community’s life in Nagybanya before World War II. I only know about one big synagogue in Nagybanya, the others weren’t synagogues, but rather prayer houses. My father rarely attended the synagogue, on such occasions he took me with him, but only on high days: to observe Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur or Pesach. Two or three times a year. And that was all.

I’ll disclose it now: once in my life I did observe a holiday. When I turned thirteen years old, my father asked me if I wanted to become a bar mitzvah. I didn’t want to, so I didn’t become. But in the same year, at the time of the great fast, on Yom Kippur I fasted. I promised to my paternal grandmother whom I loved very much that I would fast.

And I tell you that I really fasted. Because it would have had no reason at all to tell her that I was fasting, when I didn’t. Either I fasted, either I didn’t. And I did. Once in my lifetime.

Grandma was very happy. I did this for her. And I also tried out whether I was able to fast or not. I could observe great fasting. Oh, my poor grandma told me things like: ‘When you’ll grow up, you’ll have a nice Jewish wife.’ To this I always answered: ‘I will marry a woman I would love. No matter if she’s Jewish or not…’ And that’s what happened. That’s it.

Everybody spoke Hungarian with me in the family. My mother tongue is Hungarian, I didn’t speak any other language until the age of five. Later my father, who obviously had a German education, hired a fraulein for me, according to the customs of those times, and that’s how I learnt German.

I think I was five, this was after my mother died. And I got to learn Romanian only when I was six and a half, when my father simply enrolled me to a Romanian school saying: ‘You have to learn Romanian, because we live in Romania.’ And he was right. In Nagybanya there wasn’t any Jewish school, only a cheder.

There was a Hungarian school belonging to the Calvinist church, but he didn’t send me there. So I finished primary school in the Romanian public school. I finished four years of primary school in Romanian, one year of gymnasium, then in the 1940s Hungarians came in 8, and after that I learned in Hungarian, then at the university too.

My sole problem during my childhood was that I was orphan. Yet I didn’t feel so motherless, because they behaved so nicely with me. My father was not only a daddy, but a mom too. He looked after me in a very kind manner, not to speak about his parents, especially about my grandmother. Later my second mother, whom I loved a lot, took care of me very gently too. I called her by her name, Lili. I had a very beautiful childhood. The environment and the people were all very nice.

- During the war

God knows how it worked back then, but I did have all kind of friends: Jews – but just a few –, Hungarians, Romanians. We got along well with everybody, we mixed with everybody; nationality or religious affiliation didn’t mean a problem. Nationality and religion was everyone’s own business.

Especially after I learnt Romanian at the age of six, being in contact with Romanian children didn’t have any obstacles. I was very distressed when I saw they were instigating people of different nationality against each other – for this is the truth. I experienced incitement in my childhood already.

There were Hungarians, who were against Romanians, and Romanians, who didn’t like Hungarians. I don’t know why, because one can not be against one nation. You can be against a person, yes, but not against a nation. That’s it. And anti-Semitism started to be present in the 1940s, I was already eleven years old.

I had Hungarian friends, I even had friends who came to Nagybanya from Hungary, when North-Transylvania belonged to Hungary, and I got along well with them too, there wasn’t any problem. I couldn’t say they were anti-Semite. However, there were people who always talked badly of Jews.

For example it was the manifestation of anti-Semitism, that after the Germans came in – this was already in 1944 9 –, we had to wear yellow stars. Then they gathered us into ghettos. Now who took us into the ghettos? The Hungarians. What can I say? I wrote down in my memoirs that they had lodged two German officers in our house.

[Editor’s note: The memoir was published in German as part of a series edited by Roy Wiehn. In this series survivors of the holocaust describe their memories. Ioan Gottlieb: Euch werde ich`s noch zeigen (I’ll show you) – Herausgegeben von Erhard Roy Wiehn, Hartung-Gorre Verlag, Konstanz, 2006, http://www.hartung-gorre.de/gottlieb1.htm.].

We had four rooms, and in those times the army used to rent rooms for the officers. We didn’t have any problems with them. The truth is that they didn’t even talk to us. They weren’t SS officers, but Wehrmacht officers, there’s a big difference. So there were two officers.

They had an orderly too, a German soldier, who didn’t live there, but came each morning. I don’t know what he was doing for them. He was a young boy, not much older than me. We became friends. He was German, I speak German well, he chatted with me, we played together…

Well, we didn’t play childish games, we talked in the garden, things like that. There wasn’t any problem. When they were gathering us into the ghetto, first they took us to a truck, where everybody from the surroundings was forced to get up. This truck stood at the end of the street, not far from our house.

The orderly wasn’t there when they took us away. But he arrived home and found out what had happened. He ran after us, found me in the truck, we hold hands, and he wished me all the best. Not all the Germans are anti-Semite. Human relationships are complicated, very complicated.

If I know well, in Nagybanya they sent people into the ghetto on 5th May 1944. To every Jewish home a commission of few persons came, and they said: pick up a few things within a few minutes, and we’ll take you to the ghetto. Without any further explanations.

They were civilians, I don’t think they had guns, they didn’t need any. For example one of the civilians who came to us was my gym teacher. And they took us away. In the outskirts of Nagybanya there was an abandoned building, I think it used to be a brick factory or something like that, which was out of function.

They built something there, and they put us in, of course ‘la gramada’ [piled up], as one would say in Romanian, one stack to the other. I don’t know how many we were there. We had to sleep on the ground, on straw and things like that. It was prepared in advance.

My father knew about Auschwitz. In Nagybanya nobody knew anything about Auschwitz and all these concentration camps. I don’t know how, but he knew these camps existed. In the ghetto my father told me they would take us away, and we would face great torments in the concentration camp and so on, and there was no reason to expose ourselves to this.

That’s why it occurred that two or three weeks after they started to gather us into ghettos in Nagybanya, we wanted to commit suicide together with a doctor’s family. Me too. The doctor – Benedek, I don’t remember his first name –, his wife, their child, me, my dad and my stop-mother, all the six of us. With morphine.

The doctor gave us the injection. Control wasn’t so tight yet in the ghetto, so he procured a dose enough for all the six of us. Only three died from the six. He, that is the doctor, his son and my step-mother. The doctor’s wife survived, my father and me too.

One might ask why we survived. I found out then that, interesting enough, even if morphine is administered through injection, it goes through the stomach, so it gets first into the stomach, and it would be absorbed from there. So when they found us, they took us at once to the hospital, and carried out gastric irrigation.

Of course I wasn’t aware of this, because I was unconscious. Besides I was young, fifteen and a half years old, at this age the organism is very strong, and it overcame morphine. My father survived, because he didn’t know that nicotine works as an antitoxin to morphine to a certain degree. And he used to smoke a lot out of nervousness.

Such odd things can happen in one’s life. That’s how the two of us survived. I also remember that when I woke up, the bells were sounding in the Calvinist church of Nagybanya, and the hospital is quite close to the church. And I didn’t know what had happened. I didn’t know why I woke up.

We were in the ghetto for a few weeks, because we arrived to Auschwitz within a month. From Nagybanya they took us directly to Auschwitz, but this straight journey lasted for three days. I remember one bigger town we traveled through, it was in Poland already, Katowice.

We saw this on a board. Sometimes they opened a little the wagons, they let in some fresh air, but it wasn’t enough. In fact from our family me, my father, Arnold Sandor and my grandmother were deported. The four of us were together until Auschwitz. I never saw again my grandmother and my grandfather.

Because of morphine poisoning I had a discharge in my right ear – it was an external, not an internal discharge –, and I had a bandage on my head. I arrived to Auschwitz with that bandage.

My father knew so well what was going on, that when they opened the doors in Auschwitz to let everybody go out from the wagons – we had to leave there our baggage –, my father took down my bandage, and taught me: ‘If they ask you how old are you, you’ll say you’re eighteen.’ So older than I was – so he knew about the concentration camps for children. ‘And if they ask you whether you want to work, of course you want to.’

They examined men and women separately. First I parted from my grandmother, as she was a woman. We were only four from our family together with my grandmother, and so we were left three in the men’s row. There was an officer at the end of the row, he was the doctor, who said who should go to the left, and who should go to the right.

On one side there were the elder and some of the children – well, the children went to the concentration camps for children, and the old people to the crematorium –, on the other side there were those, who went to work. And so the doctor, who inspected the men’s row, asked me my age.

I spoke German, so I told him how old I was. ‘Are you willing to work?’ ‘Yes, I am.’ But I repeat that my father took down my bandage fearing that they would say I was sick, and they would then took me away… So he knew many things. And I live thanks to him.

He prepared me in Auschwitz as someone who knew what was to come. How he knew it, I ignore that. He never told me. He was too well informed, which of course was useful for me, but not as much useful for him.

I was in Auschwitz only for one week, because they sent us to Mauthausen, which is already in Austria, near the Danube. There too we were transported in wagons, but we weren’t so many people in one wagon as during our traveling to Auschwitz; we were guarded by solders.

We got to Mauthausen; we weren’t there for long either; I spent three days there with my father. In Mauthausen neither my father knew how we should handle all this, and when we were asked if there was any child, that should be taken out from there and taken to a different concentration camp and so on, my father told me: ‘My son, you’ll decide, if you want to, go there.’ I refused to go. I wanted to stay with him.

So we stayed together, and from Mauthausen we were taken to Melk.

[Editor’s note: In April 1944 a sub-camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp was established in Roggendorf, near Melk, where prisoners were forced to work in a quartz mine within the framework of the ‘Quartz Project’, for the behalf of the Steyr Works and the Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark (FMO). The camp was liberated by the Red Army in April 1945.]

Many people know Melk, because there is a famous abbey, the Melk Abbey. It is a very old abbey. The concentration camp was on the banks of the Danube. From the edge of the camp we saw the Danube. It was a small camp, with around a thousand people. There were only men. Usually they established separate camps for women and for men.

In Melk we had to work; a few kilometers far from the camp they made, or rather they wanted to make an airplane factory under the mountain. They wanted it under the mountain. Because this way it could not have been bombed. And they chose a mountain where it was easy to make tunnels, because it was mainly a sandy mountain.

We worked with pick-hammers, which are used to break the asphalt. The tools we used were smaller than these rippers, because one had to keep them horizontally, and lift it this way. It is quite annoying, because after eight hours one has such a headache, that all his body is trembling. So this is what we were doing.

Well, it wasn’t finished by the end of the war, we finished only a small part of it, the ball-bearing section, nothing of the rest was done. We made tunnels; there was a bigger tunnel and two smaller ones, I don’t know precisely; we made some five tunnels.

I don’t know how many hundred meters we had to advance into the mountain. We worked in three shifts, so eight hours. Of course the time it took to take us out there and to take us back… Those, who worked eight hours, were out of the camp at least for twelve hours. For we went there and came back, we waited, from the camp we walked to a small station, from there we took the train, so it took a long time. It was several kilometers far from the camp.

Yet there were quite many, who were working inside the camp. I also managed to work in the camp’s hospital. So I was working there, I was taking care of the sick people; it was an easier job than going out and working on the tunnels. But this had to be done as well. For example once they ordered us, who were working in the hospital, to put the corpses in a truck.

In Melk there wasn’t any crematorium, so they took the corpses to Mauthausen. I think twice a week a truck came and transported them. When autumn came, the weather cooled down – heating wasn’t even mentioned –, some thirty people died per day. On a single day. Just make a short calculation…

What happened? The number of the workforce diminished, so they brought new prisoners. So we had to put these corpses into the truck. They kept the corpses under the lavatories, somewhere in a cave; they put one on the other. Of course the lavatories were broken down, and the dirt flew over them; carrying them was a very unpleasant work.

We were I don’t know how many hundred persons in a room; we were sleeping on plank-beds, so it was a triple bed – with three levels – made of planks; there was some straw on it, but just a little, and we were sleeping on that. And they gave us a blanket to cover ourselves up. We were wearing striped clothes, alike punished people; we got the clothes in Auschwitz.

Luckily enough I didn’t get any tattooed number, I didn’t have a tattooed number, I was wearing my number on my arm. I didn’t get it in Auschwitz, but in Mauthausen. My father didn’t get a tattooed number either, we both got our numbers in Mauthausen. I was the 72762, he was the 72763, because Laszlo came after Janos.

They counted us in alphabetical order. It was written on a small iron plate, and fixed with a wire. One had to wear it on the arm, on the wrist; besides the number was written on the clothe too, on the chest, and somewhere on the trousers too.

There were not only Jewish prisoners in the Melk concentration camp. For example there were two Spanish men, I don’t know how they got there. So there were other nations too, but these were alike interior policemen, so they kept order in the barracks. The Spanish were nice people.

Later French people were brought there, also to replace the dead. One was leading the barrack, he was the blockalteser [Editor’s note: A prisoner assigned by the SS, who was responsible for the blocks], but he had an aid, who was taking notes when they called the roll, or concerning food, what was being brought and so on.

This was the schreiber. Schreiber, for he had to know how to write. In an interesting way this was a French person. Not a Jew, but a Christian French. Besides there were quite a lot of Poles, not Jewish.

There were Ukrainians, Mongols. How Mongols got there? Well, they got into the Soviet troops somewhere, and they got there as prisoners of war. There were quite a lot of Ukrainians. There was an English pilot, he got there as a prisoner of war. There was a Romanian, I don’t know how he got there. But the most of us were Jews, especially at the beginning, when we got there.

In the entire territory of the concentration camp we had to wear a colored triangle besides the number sewn on the chest and the trouser. The color of it showed the reason why one got there. There were three colors: red, black and green. The red were the political prisoners.

In an interesting way I counted for a political prisoner. I don’t know why. Why every Jew was a political prisoner, I don’t know either. The black were the thieves, the shirkers; for example they didn’t want to work, so they were sent to the concentration camp.

My boss, the leader of the barrack had a black triangle. He was there as an arbeitscheuer, he wore a black triangle; he might have come from a lockup. And there were greens, those were the murderers, who were taken out from the prison and sent to the concentration camp. Usually these were Germans.

[Ed. note: Nazi concentration camp badges, made primarily of inverted triangles, were used to identify the reason the prisoners had been placed there. The triangles were made of fabric and were sewn on jackets and shirts. These had specific meanings indicated by their color and shape: some groups had to put letter insignia on their triangles to denote their country of origin. Red triangle with a letter: ‘P’ (‘Polen’, Poles), ‘T’ (‘Tschechen’, Czechs). The most common colors were: black for the mentally retarded, alcoholics, vagrants, the habitually ‘Work-Shy’, or a woman jailed for ‘anti-social behavior’; green was for criminals; pink was for a homosexual or bisexual man; purple was for the Jehovah's Witnesses; red was for a political prisoner. Double triangles: two superimposed yellow triangles forming the Star of David was for a Jew, including Jews by practice or descent; red inverted triangle superimposed upon a yellow one, forming the Star of David was to tag Jewish political prisoners. There were many markings and combinations.]

Our superiors were SS. There were only a few Wehrmacht officers, but sometimes there were. There was a Wehrmacht doctor. Well, it wasn’t an SS doctor. For example it was thanks to him that I survived. Because I presented myself as being sick. I went to him, I told him in German that I was sixteen, and I couldn’t work anymore, if they sent me there, I would die. But I wasn’t sick, I wasn’t that sick to put me in the hospital of the concentration camp.

He kept me in the hospital all along. There were such things as well. But the others were all SS, the chief was an SS, those, who guarded us, were all SS officers, then there were soldiers, who escorted us to work. We marched in lines of five, and on both sides armed soldiers watched us. I don’t even know what kind of soldiers these were, I didn’t care in fact.

There were several barracks, and in each of them there were I don’t know how many hundred people. These were the workers’ barracks. It was set up who would go in the morning, who would go in the afternoon, who would work in the night. So there were barracks, and besides the barracks there was this hospital for example and the kitchen.

Each barrack had a chief, he was called blockaltester – altester means older, so the chief –, and he had a schreiber, who was keeping the record. But these were prisoners. The blockaltesters were trained to become sadist, then they were assigned as chiefs.

For example once my blockaltester told me he had been in concentration camps for I don’t know how many years – for some seven or eight years –, and at the beginning they had had a chief, and the chief had been told to take the prisoners to work, and from the hundred prisoners let’s say only fifteen should come back.

The others had to be executed on the way. As they could. For example he told me about that notorious quarry in Mauthausen – within the territory of the Mauthausen concentration camp in fact.

Somebody asked me: ‘Did you see the quarry when you were there?’ ‘No.’ I saw it only after the war. If I had seen it back then, I wouldn’t be here at the moment. For just a few came out of there. They were put to carry huge stones, big pieces of stones up on the stairs.

And as they were coming up with the stones, they were pushed, they fell back, the stones fell on them; a lot of people were killed with this method. And when all this was done, those, who survived, were given the same job. After they were taught what a great thing it was to be a sadist, they were made blockaltester.

Well, he behaved badly with the prisoners. Once I got scared of him. Because one morning a Jew overslept. He didn’t get up. The others were guilty too, because nobody noticed this. The truth is that people couldn’t look after even themselves enough, how they could care about the others.

And he wasn’t there at the appell. Somebody was missing. It is a big tragedy. Did he escape? What became of him? And when they found him, the blockaltester started to beat and hit him.

Suffice it to say that on that day I was at work, I didn’t know what had happened; only when I came back, the others told me that he was beating him until he could, but when he had seen he wasn’t dying, he had hung him up. And that was it. He did this with his own hands.

This blockaltester became homosexual in the concentration camp, and I was one of the young boys. Not the only one. And so he started to chat with me. But soon we weren’t on such good terms anymore, and that’s why I was sent to work. But I didn’t work for a while, he kept me around him for weeks. He gave me some other work in the barracks.

Thus I was closer to him. He told me many stories, what should I say? Otherwise, when he was in a normal mood, he was even nice. But unfortunately all this lasted very shortly. He kept on telling me stories. He told me this and that… I was afraid of him. Once he got upset on me, I don’t know why, and he ordered me: ‘Now, you’ll go to the wires.’

The camp was surrounded by those electric wires. And I started to walk, I’m telling the truth, I thought I would better die there at the wires than to live like this. And I kept on walking. He didn’t expect me to do this, he thought I was very much afraid. He ran after me, caught me and brought me back. He says: ‘I thought you were a coward.’ He had reason to think so. However, I was very close to the wires, when he caught me.

I heard stories about people who committed suicide. There was an interesting Polish family in Nagybanya. I don’t know how they had fled Poland. The man didn’t speak Hungarian or Romanian, we spoke German; he spoke a good German. His family name was Erthaim, I don’t know his first name.

He was an engineer, his wife was his own cousin. They had a child, who was a completely retarded idiot. Meaning that he was so degenerate, that at the age of four or five he was lying in bed, he made a mass there; he was only laughing, he couldn’t speak, he couldn’t walk, he wasn’t able to do anything.

They applied for permit to leave for America. America would have received them, but without the child. And they didn’t go. You’re asking why they didn’t leave there that poor creature. They weren’t able to leave. It was their single child… And they were deported. Well, this was the only case I heard about when somebody hang himself up in a lying position.

Imagine what a strength of will this requires… He was in bed, I don’t know how he had a string or what, and he hang himself up to the upper plank-bed, and he stayed there, he didn’t move until he died. Strange, isn’t? I know this because I knew that man.

The food was bad, it wasn’t eatable, to tell the truth. People broke down step by step. Not only because of the food, but their nerves and spirit were ruined as well. My father died in January 1945. We were together, in the same barrack. He was working too, and when he could, he didn’t work.

I was working in Melk for a couple of months, maybe two or three months; I didn’t work too much. I’ve told you about this huge work in the tunnels. After that I worked in the hospital for several months. By the end, during the last two or three months I was telling them I was ill, and I remained ill.

The doctor kept me there; when they let me out, I came back with some other disease, so I managed to escape work. I already knew how things worked. For example I said I had diarrhea.

If someone has diarrhea, he has to prove it. But I didn’t have diarrhea. And the officer kept me there to show it. Yet who was guarding me? It was a young boy from the concentration camp. He saw I was in trouble, and he took away the chamber-pot I should have used. Later, when the doctor asked him, he said: ‘Well, he produced it, I took it away to wash the pot.’ That’s how I could stay in the hospital for a while.

When Melk had to be abandoned, because the Russian troops were approaching, they took some prisoners on foot to the concentration camp in Ebensee. [Editor’s note: In the village called Ebensee was established one of the sup-camps of the Mauthausen concentration camp.] I didn’t have to walk, because I was on the sick-list; they took me back to Mauthausen by train.

I got back in April 1945, but I wasn’t in Mauthausen for long. Oh, I had seen there what subsequently you saw too on photos: little hills of dead bodies. Have you seen something like this? They filmed all this. For example have you seen the Judgment at Nuremberg, I mean the first edition with Spencer Tracy? There is a documentary part, which is an original film.

[Editor’s note: Janos Gottlieb refers to the movie made by Stanley Kramer in 1961 entitled Judgment at Nuremberg. One of the main roles is played by Spencer Tracy (1900-1967).]

I saw these hills, it wasn’t agreeable either. I haven’t seen anything like this in Melk. When they brought me back to Mauthausen, there weren’t any SS there anymore, the SS had left. There were policemen from Vienna who took care of the order, but they didn’t harm anybody. We were three in one bed, they gave us almost nothing to eat. The liberation of the concentration camp of Mauthausen was on 5th May. I became free four days before the war was over.

- After the war

Altogether I spent eleven months in concentration camps: in Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Melk, then again in Mauthausen. But I was in a hospital for two more months after liberation, because I became so weakened, that I couldn’t even stand on my feet. I became so weak, that they had to bring me in other hospital.

That’s how I got to the hospital of Ebensee, which was somewhat restored by the Americans, and I was fed there artificially, through my vein, until I recovered. This was after liberation. Many people died after liberation. Because there was no way back, they couldn’t have been saved. I was in this hospital for almost two months, during May and June, and I set out for home at the end of June.

I was still in the Ebensee hospital, when they gave me a paper stating that I could travel by every train for free. First I went to a concentration camp; it was after liberation, I wasn’t confined there, but I had a place where to sleep for one or two nights. This was somewhere in Austria, near Linz.

So I visited Linz on the way back home. From there I took another train to get to Hungary. I traveled a lot, because we had to go round Vienna. Vienna had been bombed a lot, trains didn’t go into that direction. So I got to Sopron – it was a big detour –, and from Sopron I traveled to Budapest.

I arrived to Budapest at the end of June. I stayed there for three or four days. In Budapest I had lodgings at once, at the railway station they announced people who came from deportation where they should go. I already heard about these centers, I already knew. I went there, and they directed me further on. They asked what I wanted, I told them I wanted to go home to Nagybanya. Romania had an embassy in Budapest, I went there too, and they also gave me a paper; then I came home by train.

It’s a different issue how we traveled. Badly, if you want to know. I looked so bad in Budapest, that when I got on into a carriage which was going to Debrecen – the train was going to Debrecen –, some Russian soldiers got on as well, and they put out everybody from the carriage saying they needed it, and they would travel in that carriage, but when they saw me, they took me back. I looked so bad.

So I traveled with the Russian soldiers until Debrecen. There I had my next train to Nagybanya. Of course I visited acquaintances in Budapest and in Debrecen as well, because I had some, people from Nagybanya who moved there. They gave me the addresses of people I knew. However, my visits lasted for a couple of hours.

On 14th July 1945, at two o’clock in the night I arrived to Nagybanya. I went to my former piano teacher – she was called Erzsebet Kadar, she was the disciple of Bela Bartok. Her husband was Geza Kadar, the painter. [Editor’s note: Geza Kadar (Maramarossziget, 1878 – Nagybanya, 1952): between 1899 and 1901 he studied at the School of Applied Arts in Budapest, then he was the disciple of Simon Hollosy in Munich. He settled definitively in Nagybanya in 1923. His wife, Erzsebet Hevesi was the disciple of Bartok.]

They were both communists in illegality, I don’t know how they escaped. And Erzsebet Kadar was Jewish, but she was christened, so she wasn’t deported. Her maiden name was Hevesi, and she had a younger sister, who was a pianist in Budapest – so they were both pianists –, and who was deported. She didn’t come back.

So I went to their place. Why I chose her? It’s an interesting matter. I went to their place, because I knew they were that kind of people who wouldn’t mind about this. For the way I looked, how dirty I was, how stinking I was, I couldn’t go no matter where. I hadn’t had the possibility to wash myself regularly.

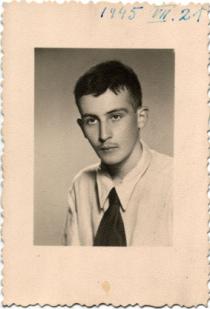

I came home to Nagybanya in my striped clothes I had worn in the concentration camp. That night I took off everything in their bathroom, I took a bath, they gave me pajamas and I went to bed. This was my first good night after more than one year. I stayed at them for a couple of weeks. I had the first photo after deportation made then. Well, I got weighed, in Nagybanya I already grew quite fat, I weighed forty-five kilos. I put on ten kilos of weight in ten days.

In the meantime I found out that my uncle, Pal Sandor was in Bucharest; I managed to get in contact with him somehow, and I went to Bucharest. He didn’t know I was going there, traffic and connections, postal services, all these were poor at that time. But his brother-in-law was at home, and he welcomed me.

My uncle was on holiday in Busteni [to the south from Brasso], but he came home instantly, and then took me there with him, and I spent there a few weeks. I recovered quite well. He asked me what I wanted, I told him, and I went back to Nagybanya. There wasn’t any problem. I kept the contact with him until he died.

So I got back to Nagybanya, and I started to make inquiries about how I could finish school. In fact there was a high school in Nagybanya, which had both Romanian and Hungarian section. I got enrolled into the Hungarian section, because it was easier for me to study in Hungarian.

They agreed that I could finish two degrees during one year as a private pupil. For I had lost one year out of my fault. I didn’t have to actually go to school, I only had to pass my exams. I was learning as I could, learning was very difficult at that time, but finally I passed my exams.

After one year I enrolled into the last, the eight degree – at that time gymnasium was of eight degrees –, and I got into my former class. Because I caught up with one year. Of course I wasn’t together only with my former classmates, because there were other newly arrived pupils as well, but most of them were my former classmates. We passed the final exams together, then everybody followed their own way.

After we had been taken to the ghetto, our house had been locked and sealed. This had been in May 1944. I don’t know precisely when, sometime in autumn – so after half a year – Nagybanya was liberated. Much earlier than we were. It was a big chaos, and the apartment was given to someone influential.

I don’t know who and how gave it to whom, but it didn’t matter, because later every apartment was given to whom the Party wanted to and so on. So when I came home, I found somebody else in our apartment – this is what it matters. Who got into my apartment?

An illegal communist called Gabor Birtas, who later became the chief of the Securitate 10. How he could occupy the apartment? He wanted to give to the Jewish community of Nagybanya all what was in the apartment. I don’t know from where a few Jews were gathered, I think they were former members of labor battalions who survived, and they formed the Jewish community of Nagybanya; it was the community who took over our belongings from the apartment.

They took out of the apartment everything they had found there, the mineral collection too. I got back a part of the collection. I still have a few pieces, I keep them in memory of my father. But I have just a few. You might ask me why. Because there was a big scandal about it, one wasn’t allowed to keep minerals, it had to be handed over to the state – alike gold and so on.

So I took the cases – the minerals were put into cases –, and I gave them in present to the Bolyai University in Kolozsvar 11. I didn’t even get a letter of thanks from them. It is there, it must be somewhere. I kept a few things for myself as souvenirs, that’s all. So I found most of the things which had been in our apartment at the Jewish community, but unfortunately not everything.

I found some of the furniture too at the community. The furniture was ours, it was our own furniture. Somehow I found our piano as well. I transported it to Kolozsvar, later we sold it and I bought a new one. I have a cottage piano even now.

I lived on aids, I was receiving aid. I went to the leadership of the town, I got assistance from the town as well, because I was an IOVR member – Invalizi, orfani si vaduve de razboi [War invalids, War orphans and War widows]. I got money from them, I got assistance from the community, so I could live on these aids.

I don’t know how I managed to live, but somehow I could go through this. And I had a great luck. One of the owners of the Phonix Factory lived in Bucharest, and he stayed sometimes in Bucharest, sometimes in Nagybanya. He was Jewish, his name was Miklos Weiser. He survived the war in Budapest.

They had deported the Jews from the entire territory of Hungary, but they couldn’t deport them from Budapest. In Budapest Jews were taken to an island, maybe to the Margit Island, and they didn’t manage to deport them all. There were too many and much too important connections between the Jews and the non-Jews, especially in Budapest, and that’s why they couldn’t deport them from there.

By the way, he got married there, he met his wife there. I know from his own telling why he got married there. For many women showed interest for him. Imagine a tall, good-looking man, who is wealthy, who has a university degree – he studied chemistry and music –, he could sing very well, he had a nice voice.

He had everything, and most of all he had money, so women were pining for him. However, he didn’t get married, because he said women all wanted to marry him for his money. But there he met somebody, who fell in love with him without knowing who he was, so he married that girl.

Miklos Weiser was very fond of my father, because my father had done for him his mineral collection besides other things. They were approximately of the same age, maybe he was younger than my father. And he helped me after the war, while I was in high school.

He helped me for real. He didn’t support me as much when I was studying at the university. This was because I went to university in 1947, until 1948 I was receiving some aids I could live on, but in the meantime – in 1947 or in 1948 – he left the country. He fled to the west.

He was right. He offered me his home. He wanted to adopt me. I didn’t want anybody to adopt me. I had my own personality, and I didn’t want to obey others. It’s not always a good thing, but that was it. They went somewhere to America, but I don’t know precisely where, maybe to Argentina.

I suppose he managed to take a lot of money with him, so he had means to live on, but unfortunately he didn’t live much, after some ten years he died of a heart attack. So he died quite early, he didn’t get old. However, while I was in high school, he supported me.

In 1947 I got enrolled to the chemistry department of the Bolyai University, and I moved to Kolozsvar. I chose chemistry, because this way I got a grant from the Phonix Factory. During my studies I was receiving all kinds of support. The Joint had a hostel and canteen for students, so I had lodgings and meal for free.

It was maintained by the Joint, and the hostel was quite in the center, in the Majalis street. I lived there during my first year of studies. After one year I got transferred to the mathematics department of the Bolyai University. I had to pass some exams, but after that I could continue the second year.

But in the meantime I got married. A different problem arose. My wife had been my classmate in high school in Nagybanya, in the last degree. I even stayed at her parents – this was the problem. She was called Aliz Butkovits, but originally her name was Aliz Berger. She became Butkovits, because her step-father adopted her.

How Aliz Berger survived the war? It’s a strange story. Her mother was christened, because her second husband was a Christian, so she didn’t have to be deported. But their daughter, though she was christened too, wasn’t married, well she was young, she should have been deported.

She was hundred percent Jewish, because her mother was Jewish too, though she was christened, and her father was Jewish – his name was Berger. But they had a neighbor, who had a vineyard in Szinervaralja – it is called Seini in Romanian –, on halfway between Nagybanya and Szatmarnemeti.

[Editor’s note: Szinervaralja is 27 km far to northwest from Nagybanya.] The neighbor brought the little girl there and kept her there until the war ended. She had accommodation and meal. That’s how she survived. They were looking for her at home in vain, they couldn’t find her.

I got married when I was in the second year, at the beginning of the second year, in autumn 1948. I managed to get a room at a relatively low price, at a Jewish family. We felt very good there. We also obtained an employment for my wife at the university, so she was earning too.

I was earning some money too, I was working. I was collecting money for the ‘Antal Mark’ – that’s how the Joint’s hostel was called. I didn’t live there anymore, but I worked for them, I was collecting money for them, thus a certain percentage of the money was mine. So I went through this somehow.

I lived in reduced circumstances for two years, then I started to earn, because in the third degree I was appointed teaching assistant. So I was a student, but I was an assistant too, I was keeping seminars of mathematical analysis for the first year. After that I had all sorts of jobs. That’s why when I retired, they recognized fifty years of teaching in higher education.

We had a son born in my first marriage, Peter Gottlieb; he was born in March 1950, when I was in the third degree. After we divorced, he stayed with his mother in Kolozsvar. This was normal, because he was five or six years old, when we divorced, so he was a little child. I couldn’t have raised a child here, in Iasi.

That was it, but when he started his university studies, he stayed at me. He finished mathematics here. He got back near Kolozsvar, than to Kolozsvar; he got married there, his wife is Romanian. They left for Israel in 1989, a few months before the fall of Ceausescu 5.

My son died in December 1996 – he was forty-six years old –, he had cancer. But I have two grandchildren in Israel. They have Romanian names, one of them is Mircea, the other is Silviu. For usually it is the mother who chooses the names. But when they left for Israel, both of them adopted Jewish names. Mircea became Miha, Silviu became Yossi.

They were born in 1979, respectively in 1983. Both of them have already finished high-school and the army service, and they are students now; the elder, Miha is studying economical sciences in Jerusalem, the younger, Yossi studies psychology in Beer Sheva. Their mother lives in Sderot, but they don’t stay with their mother anymore.

The Bolyai University invited very good teachers from Hungary to Kolozsvar; only a few of the teachers were from Kolozsvar. I received a very good teaching in mathematics, which was useful all my life. In my opinion I had excellent teachers. Samu Borbely was not only a mathematician, but an engineer as well, and he had been working in Germany for a while, for example I think it was him who calculated the profile of the wing of the Stuka or some other aircraft.

[The Stuka – from Sturzkampfbomber – was a dive bomber designed by the Germans in 1935-36; its official name was Junkers Ju 87.] He wasn’t a follower of Hitler, he didn’t have any problems of political nature, but when he saw what was coming, he left Germany.

However, he was very well trained, and he was a mathematician of an excellent pragmatic sense. [Editor’s note: Samu Borbely (Torda, 1907 – Budapest, 1984) – mathematician, university teacher, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He studied at the Technical University of Vienna, then he was assistant professor there; from 1933 he was the mathematician of the Institute for Aviation Theory within the university. In 1941 he moved to Kolozsvar, and he was assistant professor, lecturer, then external lecturer at the Franz Joseph I University.

In 1944, after the German occupation of Kolozsvar he was arrested, and he was taken to Budapest, then to Berlin, where he was imprisoned. In December 1944 he returned to Budapest, at the end of 1945 to Kolozsvar. From 1945 he was professor at the Bolyai University; he was the head of the department of mathematics from 1949 at the Technical University of Miskolc, from 1955 at the Technical University of Budapest. Between 1960 and 1964 he was the director of the Institute of Mathematics within the Faculty of Engineering Industry, University of Magdeburg, then, between 1964 and 1968 he was head of department again in Budapest.]

Professor Rezso Gaspar had a less pragmatic, but a thorough theoretical grounding, and he had very good courses, for example on the theory of manifold and on real functions. Rezso Gaspar came from Hungary, I think he died in Debrecen, if I know well, he died a few years ago.

[Rezso Gaspar (1921–2001) – academician, university teacher.

Between 1943 and 1945 he was teacher at the Reformed College of Papa; between 1945 and 1953 he was teaching at the Institute of Physics of the Technical University of Budapest, in 1953 he became the head of the Department of Theoretical Physics of the Lajos Kossuth University of Debrecen. He performed a scientific work of pioneering significance in the field of quantum chemistry. He established an internationally acknowledged scientific school at the Department of Theoretical Physics of the University of Debrecen.]

Jeno Gergely was our only teacher who didn’t leave Kolozsvar. In fact he was already an assistant professor during World War I. Between the two world wars he didn’t leave Kolozsvar, because he got married there, so he stayed there and taught in a high school.

When in 1945 the Bolyai University was established again – by that time it was called Bolyai University, I don’t know what was it called before [Editor’s note: Franz Joseph I University, between the two world wars King Carol II Institute] –, they took back uncle Gergely.

[Editor’s note: Jeno Gergely (1896–1974) – writer of scientific works, expert in the Non-Euclidean geometry. Between 1920 and 1948 he was teaching in the Marianum Gymnasium for girls; from 1947 until his retirement he was professor at the Bolyai University, then at the Babes-Bolyai University.]

Uncle Jeno was an excellent teacher, and he was reading constantly, so he had a very good general education too. We always used to say that he was a walking encyclopedia. When he was asked something, he always could tell where that specific information was to be found. He was teaching mainly geometry, the theory of curved surface, differential geometry and so on. By the way, he was my tutor when preparing my thesis. It was on calculus of variations, but he suggested me the subject.

Then there was Gyorgy Pick, we all called him Gyuri Pikk. Previously he was a high school teacher. He was a magnificent expert in algebra. [Editor’s note: Gyorgy Pick (1907–1984) – between 1945 and 1952 he was teaching algebra at the Bolyai University of Kolozsvar; he was the founder of the school of algebra within the Babes-Bolyai University. He was the leader of many PhD theses written by Hungarian mathematicians of Transylvania (www.emt.ro/kiadvanyok/msz/msz2000/msz37.pdf).]

We had a teacher with a thorough grounding in physics as well, Tihamer Laszlo. He was a good experimental physician. [Editor’s note: Tihamer Laszlo (1910–1986) – physician, university teacher. Until 1944 he was the physics teacher of the Unitarian College, in 1947 he became head of department at the Bolyai University. He was the author of many course books and lecture notes.]

May he have not had a much too brilliant brain, but in the first year such people are needed, not prominent men of science.

And there was Teofil Vesca – who later came to Iasi, and I got here after him – who had very nice courses in the theory of physics. I attended his courses of theoretical mechanics, then a general theoretical course in physics. He had a very rich education, and most important, he was very productive. He died here, in Iasi, at the age of fifty, yet he had published more than hundred and fifty works of mathematics and physics. He had at least three diplomas: in mathematics, physics and philosophy.

At the Bolyai University he kept his courses in Hungarian. He spoke Hungarian as he spoke Romanian. This fellow had the courage to write down once, when he had to fill in a form with his personal data, that his nationality was Transylvanian. Not Hungarian, not Romanian, he was a Transylvanian.

Ferenc Rado was an excellent teacher and a very good educator, and he was outstanding as a scientist as well, he wrote very good studies. I think he died at the age of sixty-six because of rectal cancer.

[Editor’s note: Ferenc Rado (1921-1990) – writer of mathematical works. He was a high school teacher, then from 1950 he was lecturer at the Bolyai, respectively Babes-Bolyai University; from 1968 until his retirement (1985) he was university teacher. (www.banaterra.eu/magyar/I/irodalmi_lexikon/irok/irodalmi_lexikon.htm)] To resume all this, I had good teachers. This is the truth.

The young generation was also good. I could mention my friend, who is a few years older than me, but at that time he was already an assistant professor, Zoltan Gabos; he is also a correspondent member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.