Hana Rayzberg

Riga

Latvia

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: August 2005

I conducted this interview with Hana Rayzberg at her home. She lives in a rather spacious three-room apartment on the ground floor of an apartment block built in the 1970s. Hana has many books and pot plants at home. She has family pictures on the walls. Hana is a short, plump lady. She has short-cut gray hair. She is very friendly and hospitable. Hana is smart and has a sense of humor. She’s been a continuous monitor in the Jewish choir, established 15 years ago in the Latvian society of Jewish culture. The choir is like a family to her. She loves the choir members and cares about them. During the interview two choir singers visited Hana. They looked like it was quite common for them to drop by to see this sweet, friendly woman, have a chat with her and just enjoy the friendly atmosphere. Despite her hard and complex life Hana radiates the love of life and optimism.

My family

Generation after generation my father’s family lived in the Latvian town of Ludza [about 250 km east of Riga]. At that time Latvia belonged to the Russian empire, and Ludza was located within the Pale of Settlement 1, where Jews were allowed to reside. Perhaps, for this reason Jewish residents constituted about 70 percent of the population of Ludza. Jews mainly settled down in the center of the town. There were many shops and stores owned by Jews in the center. There were not many Latvians, but there were many Russians in the town. For the most part, they were Old Believers 2. During the Russian empire regime Ludza was assigned to the Vitebsk 3 region in Russia, and when Latvia became independent in 1918 4, the Russian residents stayed to live there.

I never knew my grandmother Hana Edelstein, my father’s mother. She died before I was born. I knew my paternal grandfather Dovid-Leib Edelstein. He owned a store of leather goods. My grandmother was a housewife.

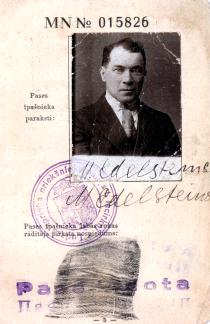

There were three sons and two daughters in the family, five children in total. I didn’t know my father’s two older brothers. They moved to Africa before I was born. I don’t even know their names. My father was born in 1886, and was given the name of Elieizer-Meishe. When he fell seriously ill in infancy, he was given another name, Haim, to swindle death. In his documents his name was written as Haim-Elieizer-Meishe Edelstein. My father’s sisters were born after my father. The older one’s name was Slava, or Slove in the Jewish way. Taube, the younger one, was born in 1893.

My father, his brothers and all boys in this small Jewish town studied at the cheder. My father could read and write Hebrew. I think he also had a secular education, but I never asked him about it. My father’s parents were religious, and it couldn’t have been otherwise in this little Jewish town. They went to the synagogue on holidays, celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and observed Jewish traditions. There were a few synagogues in Ludza. They were guild synagogues: traders’, tinsmiths’s, bakers’ and tailors’ synagogues. They were small synagogues, of course.

There was a shochet, and housewives brought their chickens to him to have him slaughter them following the kashrut rules. All Jews in Ludza were religious. All boys were circumcised shortly after they were born, and had their bar mitzvah at the age of 13. Bar mitzvah was a mandatory ritual. All Jewish weddings followed the Jewish traditions. Even the poorest families had a chuppah, and the rabbi of the synagogue visited by the parents of the bride or the bridegroom, conducted the wedding ceremony.

All Jewish stores were closed on Saturday. I remember a whole street with just Jewish stores in Ludza. They were all kinds of stores selling all kinds of goods, including clothes, shoes, hardware, food, etc., and they were all closed on Saturday. Non-Jewish residents did their shopping beforehand, knowing this tradition. There was also a Jewish school in the town. All subjects were taught in Hebrew.

The majority of the residents of Ludza were well-off. There were also poor families, but there were no beggars. The Jewish community of Ludza was very strong, and the better off supported the poor. Women, involved in charity activities, visited poor homes to give them some money. They ensured that all poor families had a festive dinner on Sabbath and Jewish holidays and sufficient clothes and food in general. Jewish houses in the town were scattered around the town. Jews built their houses where they could afford to buy a plot of land.

My father worked in my grandfather’s store. Slove, the older sister, got married and moved to her husband in Riga. Her marital name was Dubin. Her husband was Mordukhai Dubin. [Editor’s note: Mordukhai Dubin (1880s – 1941): statesman, Seim deputy, represented Agudat Isroel, the Party of religious orthodox believers in the Latvian Seim. Dubin was at the head of the Jewish community of Latvia. He was a businessman and had ties in international financial circles. He continuously arranged for Latvia to obtain loans on most advantageous conditions.] They had three children. The older one was their daughter Hinda, and after her their son Zalman was born. I don’t remember the name of Slove’s younger son.

My father’s younger sister Taube was very pretty and kind, but she never got married for some reason. She lived with our family her whole life. Taube also worked in my grandfather’s store.

My mother came from the Latvian town of Jelgava [about 50 km from Riga], which was called Mitava at the time. Several generations of Mama’s ancestors lived in Mitava. My maternal grandfather’s name was Dovid Gelbart, and my grandmother’s name was Basia. Mama told me that my grandmother’s father Haraf Illarion was a rabbi in Mitava. I don’t know what my grandfather did for a living. My grandmother was a housewife.

There were six children in the family. I don’t know in what sequence they were born. Mama was born in 1899. She was named Debora 5, and the Jewish name in her certificate was Hasia-Dveira. Mama’s brothers’ names were Yakov, Yankl in the Jewish manner, and Elias [Grigoriy]. I don’t know the name of Mama’s third brother. Mama’s sisters were Rosa and Polina.

When World War I began, the Russian tsar Nicholas II 6 ordered to deport Latvian Jews to Russia, fearing that they might support the Germans. Mama told me they were ordered to leave Mitava for Russia. They moved to Penza region where they lived till 1917. When the Russian tsar was dethroned during the revolution 7, residents of Latvia were allowed to return to their homes. Mama’s family settled down in Liepaja [about 200 km from Riga], on the Baltic Sea.

Mama’s parents were religious, and all children received a Jewish education. The family observed Jewish traditions at home, celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and followed the kashrut according to Jewish rules. The children also received a secular education. There was a Jewish quota in Latvian higher educational institutions 8. Mama’s brother Yakov went to study in Tartu [170 km from Tallinn]. There were no restrictions concerning Jews in Estonia even during the tsarist rule. Even non-residents of Estonia could get an education in Estonia. Yakov graduated from the Medical Faculty of the University of Tartu and stayed in Estonia. He was married, and I believe he had three children, but I can’t remember their names. Yakov and his wife lived in Tallinn and he worked as a doctor.

Mama’s brother Elias, called Grisha in the family for some reason, became an engineer. The third brother moved to Germany. I think this was before the revolution. He got married in Germany. His wife’s name was Lotta. I don’t know whether she was Jewish or German. They had two sons. Mama’s sister Rosa married Hodes, a Jewish man from Riga. I don’t remember his first name. Their only daughter’s name was Esther. Polina was single and lived with my grandmother and grandfather.

Mama studied at the Teacher’s Training School in Liepaja. Then she continued her studies in Riga where she finished the Teachers’ Training College. Mama was an English teacher. I don’t know how my parents met. I asked Mama about so little. I should have asked her more questions! The older you grow, the more you want to know about your roots. I wish it had happened before it was too late. When one is young one does not care about what happened in the past, when one works, one doesn’t have time for this, and when this finally becomes important, there is no one left to ask. All I remember of what Mama told me is that she and my father got married in Riga on Pesach in 1925. It goes without saying that they had a traditional Jewish wedding with a rabbi and a chuppah. Later my parents moved in with my grandmother and grandfather in Ludza. I was their only child. I was born on 1st January 1927 and was given the name of Hana-Leya after my paternal grandmother.

I have bright memories of the house where I spent my childhood. It was a wooden house in the center of the town. It was passed on from one generation to another. Even when my grandmother and grandfather received it, it wasn’t new. It was called the ‘big house.’ There was a smaller three-room house in the yard where our relatives and their children stayed when visiting us in the summer. Grandfather, Aunt Taube and our family lived in the bigger house. There was a fruit orchard and a vegetable garden near the house. There were no comforts [toilet and bathroom] in the house. There was a stove heating the house. We fetched water from a well.

A few years ago, when property restitution began in Latvia, I took my family to show them the house. My son was disappointed with what he saw, particularly since I had given such a colorful description of it before. I looked at the shabby wooden house that didn’t even have a foundation, but it was dear to me. It was full of my childhood memories. I had a happy childhood, and the house was a part of this happy life. Somehow the house was in the ownership of the female members of our kin. My grandmother Hana Edelstein assigned it to my father’s sister Taube.

Mama went to work as an English teacher at school. There she developed a severe disease: retinal detachment. Mama started loosing sight. I don’t know how her pupils found out, but they cheated right before her eyes. Mama left school and took to giving private classes. Every six months she had to be examined and take a course of treatment. She went to see a doctor in Riga where my father’s sister Rosa Dubin lived. I went with her. We stayed in a big brick house in the center of Riga. We took a horse-drawn cab to get there from the railway station. We were very close with Rosa. Rosa and her family spent summers with us in Ludza. During our trips to Riga we also met with Mama’s sister Rosa Hodes. Once Mama took Rosa’s daughter Esther and me to watch the children’s opera ‘Puss in Boots’ at the Opera Theater. I enjoyed the theater and the opera very much.

Jewish traditions

My parents were religious and observed all the Jewish traditions. Of course, some Jews in Ludza attended the synagogue twice a day, but not our family. My family went to the synagogue on Sabbath and on Jewish holidays. Nobody worked on Saturday. On Friday my father closed his store early. On Friday Mama cooked sufficient food for two days. On Sabbath she cooked cholent and potato and meat stew in a ceramic pot. Cholent was usually cooked in the Russian stove 9, and she left the pot in it till Saturday dinner time. We had no Russian stove, but the woman living as far as three houses away from where we lived had a stove. Her neighbors left their pots with stew in her stove following the rules. On Saturday a Russian woman came to help us start a fire in the stove, turned on the light and boiled the kettle. On Friday Mama lit candles and prayed over them.

On Saturday morning my parents went to the synagogue. When I started walking, my parents took me with them to the synagogue. After the synagogue we visited our relatives. We had many of them, close and distant relatives living within three or four kilometers from where we lived. They also visited us. Our house was halfway between the railway station and the center of the town, and all those relatives visiting Ludza came to see us immediately. My father discussed newspaper articles with male visitors. We spoke Yiddish at home.

We celebrated Jewish holidays according to the rules. One businessman in Ludza purchased matzah in Riga before Pesach and sold it to Jews in Ludza. There was no bread at home throughout the duration of the holiday. We only ate matzah. All housewives cooked traditional Jewish food: gefilte fish, chicken, desserts like keiglakh, imberlach, delicious candy made of carrots and lemon peels. The house was thoroughly cleaned before Pesach. All breadcrumbs or pieces were wrapped in a piece of cloth and burnt.

On Pesach my father conducted seder. Two were conducted on the first evening, and one on the second evening. Mama had special dishes stored separately from our everyday dishes and they were only used on Pesach. They were taken out on the eve of Pesach, when the house was cleaned from chametz. There was a glass of wine for Prophet Elijah in the center of the dinner table. Elijah came to every Jewish house to bless it. My father wore white clothes to conduct seder. There was Haggadah reading and buying out the afikoman. My parents knew Hebrew, and I learned it at school.

We also celebrated Rosh Hashanah, Purim, Chanukkah and Yom Kippur. On Yom Kippur my parents fasted, and I joined them when I grew older. I sat at the synagogue with my mama on the balcony.

There were also other holidays. There were military parades in the central square of Ludza on Latvian national holidays. There were brass orchestras playing, and Jews made up the majority of musicians. They commonly worked as barbers or shoemakers, and played in orchestras on holidays.

We also celebrated birthdays in the family. Mama had her birthday in summer, and we always had birthday parties in the garden. We only had some wine on Jewish holidays, and on birthdays we had tea, sweets and desserts. Adults talked and sang Jewish songs, and children played in the yard. I remember once somebody asked me how old Mama turned on her birthday and I replied that she turned old, and that was when she was just 36! And now when someone turns 70, I think he or she is a young person.

My early school years

At the age of six I went to the preparatory grade of the Jewish school. We studied the basics of Hebrew, and learned to read and write in Hebrew. We had Hebrew classes every day, and all subjects were taught in Yiddish. I studied in this school for six years. We also had religious classes where we studied the Tannakh and Torah. I did well at school. I had a happy childhood. These were the happiest years of my life. We were not quite wealthy and Mama couldn’t afford to buy a piano for me. I attended a music studio where I had classes. I also performed at school parties playing the piano. I played pieces by Brahms and Beethoven.

There were a few lakes in Ludza, and children spent most of their time in the summer on the banks of these lakes. We bathed and went rowing, picked hazelnuts - walnuts don’t grow in Latvia - on the opposite bank in the woods. My cousin sisters and brothers spent their summer vacations with us. It was a happy time!

My grandfather spent much time with us. We got together at the table and had tea from the samovar. We drank tea with lumps of sugar in our mouths. One of the youngest children used to sit on Grandfather’s lap. My grandfather had a beard and it felt ticklish when he kissed us on the nose. He told us stories from the Bible [Old Testament] that sounded like fairy-tales to us.

Unfortunately, in 1931 my grandfather had a stroke and was paralyzed and couldn’t speak. He died in 1932 and was buried near my grandmother’s grave at the Jewish cemetery in Ludza. I didn’t attend the funeral, but I know that it was a traditional Jewish funeral. During the funeral my parents’ friends took me to their home. My father’s sister Taube moved in with us after my grandfather’s funeral.

In 1933 Hitler came to power in Germany. It also affected our family. My mother’s brother and his family lived in Germany. When we read about the ‘Crystal night’ 10 we knew they were in mortal danger, but we still had hope they would manage to escape. My maternal grandmother Basia Gelbart was a very energetic woman and she managed to obtain a permit for her son and his family to leave Germany, by cooperating with Dubin, deputy of the Latvian Seim. They managed to escape taking the last boat to the USA. They settled down in Philadelphia.

Mama corresponded with her brother before the Soviet occupation in 1940 11. This correspondence terminated during the Soviet regime 12. I worked in the ministry after the war, and if they knew I had relatives living abroad they would have fired me. When perestroika 13 allowed correspondence I wrote to my uncle. His wife Lotta replied that he had died. This was the only letter I wrote to Lotta.

I finished the Jewish school and passed exams to the Latvia gymnasium [grammar school], the only possible option in Ludza. All subjects were taught in Latvian, and it was difficult for me. We also studied Latin, German and English. I was good at foreign languages. I was also very fond of chemistry. I was thinking of continuing my studies after school to become an interpreter or a teacher, but this was not to be.

Hitler’s coming to power in Germany affected Latvia as well. Anti-Semitism emerged after the coup in 1934 14. There were only five Jewish students in the gymnasium: four girls and one boy. His name was Hertz Frank. He became a documentary film producer. All of us came to the gymnasium after finishing the Jewish school. We had double names, and these names were listed in the class register. Usually teachers called us by one name, while our history teacher used to call us by our double names emphasizing on the foreign pronunciation of our second names. He kind of segregated us from other students. We also studied religion in the gymnasium. Jewish students had their own teacher. I don’t know whether he was a rabbi, but we studied the Bible [Old Testament], Torah and Talmud with him.

In 1938 a big fire burned down Ludza. Most of the buildings in the town were made of wood, and the wind spread sparks to large distances starting new fires. Local firemen and firemen from other towns were fighting the fire. It took them a lot of effort to put out the fire. Many people were injured and many lost their homes to the fire. Fortunately, our house escaped the fire, but we had our belongings taken outside and stayed outside the whole night until we started taking them back into the house in the morning. Mama also gave shelter to three families that had lost their homes. One family was the family of my classmate, and as it turned out later, they were all anti-Semites. He used to say at school that all Jews were bad, but that our family was an exception.

My close friend Rokha Feiman came to Ludza from a small town in 1938. She had finished her studies at a six-year Latvian school and had to move to a bigger town to continue her studies. In Ludza she entered a Latvian commercial gymnasium. Rokha’s parents rented her a room from us and we shared our meals with her. She was three years older than me, but this fact didn’t affect our friendship. We were like sisters. Rokha helped me with my Latvian. She stayed with us till the end of June 1941 when she went home on vacation.

The war

In 1939 Hitler’s armies attacked Poland 15. I was too young to understand what was going on. My parents knew the situation and were very concerned about it. My father’s acquaintances used to discuss events at our home and I could tell they were disturbed. After the Soviet Army entered Poland and the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact 16 was executed, Soviet military bases were established in Latvia. In 1940 Latvia was annexed to the USSR 17.

I remember that the Soviet military were given a warm welcome, at least, in Ludza. Political prisoners were released. The Communist Party wasn’t allowed in Latvia, and Communists had been put in prison. There were meetings in the market square. Soviet military walked the streets with accordions singing Soviet songs. Residents of Ludza also sang and danced in the streets. Girls wore red kerchiefs on their heads. There was a wooden stage installed on the square and the Soviet military arranged concerts there. We, children, joined the festivities and it was a lot of fun.

The Soviet military were accommodated in residents’ houses. They had money and rushed to buy things in stores. They were particularly buying lots of chocolate. We found it strange. Why buy so much at once? Then an accident happened, when a landlady stoked her stove and two Soviet military got gas-poisoning. One managed to crawl outside, but the other one died. Of course, this might have been an accident, but the military hesitated about getting accommodation in Latvian houses. They preferred Jewish households.

Two of our rooms were given to Soviet lieutenants. I remember that one of them came from Sverdlovsk region. His name was Kryuchkov. They were friendly and told us about life in the USSR. Some things were hard for us to understand. One military said that his mother had to go to a store at 7am to buy milk. Our stores had a plentiful supply of goods, and we didn’t know why go shopping so early in the morning. Before the first year came to an end, we understood what it was like. Many goods disappeared from shops. Many goods could only be acquired by coupons. I remember the stamp ‘fabric three m’ on the last page in my father’s passport, and another one beside it: ‘Released.’ It was the same with clothes and shoes.

However, before this situation developed, there were funny things happening. The wife of one of our tenants was visiting him. She came from a small mining town. There was a dance club where everybody spent the evenings. This woman bought a luxurious night gown with laces and embroidery and, thinking that it was an evening gown, she went to the dance club!

The Soviet authorities closed the Jewish school in Ludza. Our gymnasium became a Latvian general education school. We started studying the history of the USSR. My friends used to visit me in the evenings and our tenants joined us for an evening. We were flattered by this attention the officers in their uniforms showed us. They told us about the USSR and their life. Sometimes they sang Russian songs, and one of them played the accordion.

The 14th of June 1941 became the black spot in the history of Latvia. This was the day of deportation 18. Later we found out that there had been lists generated in advance, and local communists were involved in their compilation. People were deported at night. NKVD 19 officers drove to houses, gave families a little time to pack and drove them to the railway station where trains were waiting for them. This was done quietly and in secret. It was frightening to get up and find out that one of your neighbors or acquaintances had been deported. Husbands, wives, their children and old parents were gone. There were wealthier people among them, but also those who worked hard to provide well for their families. Of course, there was intelligentsia and many Jewish people among them.

Men were taken to the Gulag 20 to timber cutting, and children and women were exiled. This was terrible, but in the long run, this saved the life of many of them. The intelligentsia or wealthy people would hardly have evacuated during World War II, hoping that the Germans would restitute their property nationalized by the Soviets. There were hardly any Jewish survivors in Latvia after the war while many of those that had been deported survived, though many died from hunger and hard work. However, at that time nobody had any thoughts of this kind.

A week after deportation the Great Patriotic War 21 began. Germany attacked the Soviet Union on Sunday, 22nd June 1941. There were distant explosions and artillery cannonade heard in Ludza. Camouflaged trucks with military on them were passing through the town. We were used to frequent military trainings, and thought this was one of them. At noon Molotov 22 spoke on the radio. He said it was the war. Papa’s older sister Rosa’s daughter Hilda was visiting us then. When the war began, my parents decided to take her back home to Riga. They thought it was better for the family to keep together at the time of war. Unfortunately, this was the wrong decision.

In the first days of the war many people were coming to Ludza from other towns and from Lithuania. They headed to the East, and occasionally they asked residents of Ludza for some water or bread. We already knew that the German Air Forces bombed Riga. There were no transportation means to leave Ludza. My parents decided to leave on foot, anyway.

We locked our apartment, took some food and water for the road and headed to the village of Golyshevo, five kilometers from Ludza. It was located on the border with Russia. There were numbers of other escapees there, but the border guards didn’t let anybody cross the border. We were sitting on the ground, and waiting for 24 hours. The heat was oppressive, and people were fainting. I was whispering prayers begging the Lord to make them let us go. We had no luggage. All I had with me were a few pictures from the family album.

Twenty-four hours later the border guards told us to go back home. We returned home, but 24 hours afterward we heard that the border was open and we went to Golyshevo again. When we left the house, we saw the rabbi on the corner of our street. He asked us, ‘Jews, where are you going?’ He stayed in Ludza and was killed. Many Jews stayed in Ludza hoping for the best. None of them survived.

We crossed the border with Russia and went through the military residential area in the village of Krasnoye. We marched in a column of escapees. Every now and then German aircrafts dropped bombs onto us. We walked through the woods that were safer, but it was very tiring. People were leaving their bags and suitcases on the way. There were four of us: my parents, Aunt Taube and I. Shortly before the war, Mama gave me a bright red knitted woolen suit on my birthday. I was sorry to leave it and put it on, when we were leaving our home. I also wore high leather boots that were in fashion then. I left my boots and walked barefoot, but I had no other clothes with me to wear, but my suit. It was very hot, and when I finally got a chance to take it off, my skin was the same color as the suit.

We walked day and night, making short stops to sleep. We were scared. Nobody knew where German soldiers might come from. We met Soviet soldiers returning from battlefields. They were wounded, bandaged and bleeding. There were dead cows and horses lying around. We covered about 200 kilometers and were exhausted. In one village a very hospitable Russian family invited us to their house. They gave us some food and offered us to take a rest on the Russian stove bench bed. We were dozing, when another bombing started. The owners of the house were telling us to stay with them for some time, but we were afraid of the approaching front. It was hard to understand where the Soviet or German forces were. Everything was such a mess during the first days of the war.

We reached Mga station. On our way Mama and I were given a lift on a Soviet military truck. The truck was camouflaged with birch tree branches. The driver speeded up, and it was a miracle that we didn’t fall out on the road bumps. Then another driver, who was coming in the opposite direction, told our driver that there were Germans ahead of us, so the driver turned onto another road. We drove as far as Lokno station, Pskov region, [700 km west of Moscow] where we got off. We knew those Soviet Army soldiers rescued us and it was a miracle! In Lokno many families were waiting for whatever information, sitting in the park near the station. There were rumors that we might expect trains for evacuation to arrive. We met with my father and aunt, who had arrived on a different truck.

Finally the train with open cars, which had been used for coal shipments before, arrived. The floors were covered with coal dust. We boarded the carriages. The train was still at the station, when a German aircraft appeared and started dropping bombs on the station from low-level flight. There was a big weapon and ammunition storage near the station, which was their target. A few bombs fell onto the train. People were screaming. Some were killed and there were wounded people as well. I climbed into a big barrel near the storage facility. I was so scared that I didn’t realize that I was climbing into the very center of bombing. When it was over I heard my parents calling me, but I couldn’t reply. I lost my voice from fear. It took me quite a long time to recover my voice. Fortunately, our family survived.

The survivors boarded the train again and it started in an unknown direction. At Velikiye Luki station my aunt got off the train to fetch some boiled water, when the train departed. My aunt never caught up with the train and stayed at the station. We finally arrived in the village of Pogiblovka, Nizhniy Novgorod region [500 km east of Moscow]. Eight families from Ludza happened to stay in this village.

Our family was accommodated in a local house owned by Aksinia. Her sons were at the front, and she was alone. Basically, there were no men left in the village. There were only a few older men living there. Aksinia was a kind and nice woman. She supported us a lot. We were provided with flour, but had no idea of how to bake bread. Aksinia showed my mother what she needed to do, and also, baked bread for us. Mama spoke a little Russian and could communicate with the locals. I also spoke a little Russian, but I was very shy because of my accent. The locals treated us well.

I remember shortly after we arrived some local young people invited me for a walk in the village. The only young man in the village was a cripple since childhood. He played his accordion and sang Russian songs. I walked arm-in-arm with local girls. The girls were singing. I was very shy, indeed, but their sympathy and friendly attitude helped me to cope with it. It didn’t take long before my Russian improved so well that I could at least be understood.

We would have hardly survived in evacuation, if it hadn’t been for my mother. Mama was very skilled and liked handicrafts. Aksinia gave her little pieces of leftover fabric, and Mama made a beautiful quilt blanket. Our landlady showed it to her neighbors, and since then Mama continuously had orders from new customers. She assembled the quilt pieces and made patterns with them. Her customers paid her with food products, and it was of big assistance to us. Mama also knitted warm cardigans, woolen socks and mittens for winter.

The situation at the front got more tense. Often German planes flew over the village. German forces were approaching Moscow. However, they only dropped flyers reading ‘Away with zhydy [Yids] and Communists!’ Often death notifications were delivered to the village. They caused lots of grief and tears.

We had no warm clothes with us. I kept wearing my red woolen outfit, and Mama only had one silk summer dress. My father wore his only suit. Once, the chairman of the collective farm asked my father to dig a grave to bury a dead horse. After that one could never identify the piece of clothing my father had on. We were horrified to think about winter. We also realized that if the Germans advanced, none of us would survive. One Jewish family moved to Central Asia where they didn’t need winter clothes. They wrote to us from there convincing us to join them. The remaining families headed to Central Asia. It was difficult to get there. The trains didn’t follow their schedules, letting military trains pass. These military trains, loaded with weapons, were camouflaged with birch-tree branches. It also happened that civilian passengers had to get off to give place to recruits to get on platforms to go to the front.

It took us over a month to get to the destination point. I fell ill on the way. I had high fever. There were no medications available. We finally arrived in Central Asia. We were accommodated in Andijon region, Uzbekistan [over 3500 km south-east of Moscow]. This was a Muslim town, and all women were in purdah. We didn’t speak the Uzbek language, and they spoke no Russian. We were accommodated in a clay kibitka hut. Three families shared the only room in this hut.

We experienced a terrible earthquake there. All of a sudden it grew dark one bright sunny day. We heard screams outside and ran out of the room. The hut fell down before our eyes. I remember the earth parting right in front of me, two or three steps away from where I was standing. The water in the river grew dark, and there was bright white foam on black waves. The houses around were falling apart and people were screaming from horror.

We were not given food cards 23. We worked in the local cotton growing collective farm. My father was digging up the farmland, and Mama and I pushed heavy carts loaded with fertilizers. Each employee was paid with one flat bread for a day’s work. The locals treated us nastily. I don’t blame them. There were evacuated people accommodated in each local hut. The village was small, and there was no extra space, and of course, they didn’t like the idea of sharing their lodgings. Also, they had to share their food with these newcomers. We were followed by their exclamations ‘Rus is bad! Rus is bad!’ We knew they were right to a certain extent, but this understanding made things no easier.

Mama told us we had to get out of there while we were still alive. She found the first family that left Pogiblovka in Andijon, and we went there. All local houses were packed with evacuated people. Mama found an Uzbek man. He promised to lease his kibitka hut to us. His wife was dying of some infection in this kibitka. So, he promised that when she died we could move in there. So we stayed outside waiting till she died. The nights were warm, and we slept beside the kibitka hut. The landlord gave us a few armloads of straw, and we slept on it. I had no shoes, and my red outfit turned into rags. Some woman felt sorry for me and gave me canvas shoes and a gown. At night, when I fell asleep putting my shoes beside me, they were stolen, and again I had to walk barefoot.

When finally our landlord’s wife died, we managed to move into this kibitka with another family of evacuated people. It goes without saying that no disinfection took place. Shortly afterward we fell ill with typhoid. Fortunately, we all survived. We also had to watch out for scorpions before going to sleep. Their bites also might have been lethal.

We actually starved. There were all food products sold at the market, but we had no belongings to trade for food. Fortunately, the spinning shop owner felt sorry for us. He hired Mama and me to work night shifts. I was under 16, and according to the current law, I had no right to work. The work place was a few kilometers from where we lived. I also had to cross the railway. The bypass was a long way, and the railroad was full of trains loaded with weapons and ammunition. Mama and I took the risk of crossing the railroad track under the trains never knowing, when the train would start moving.

I turned 16 in Andijon and received my first passport. Mama was very concerned about my having to work instead of going to school. She finally convinced me to go to school and work afternoons. I went to the local school, and two weeks later all schoolchildren had to go to harvest cotton at a collective farm 24. We worked in the morning and in the evening. The daytime temperature was +50°С. I fell ill with tick-borne typhoid. I had high fever, and was unconscious most of the time. There was no doctor available. The school deputy director, an elderly Jewish man from Dnepropetrovsk, took me to Mama on a wagon. He saved my life, but I didn’t go back to school.

We starved, but actually, all those in evacuation were in a similar situation. People were lying in the streets, swollen from hunger and unable to get up. They were dying, and passers-by just stepped over their bodies. Hunger was particularly hard on men. In spring 1942 my father developed dystrophy. On 8th May 1942 we took him to hospital. He couldn’t walk. In the hospital the receptionist wrote, ‘No vacancies’ on my father’s prescription and we were told to go back to where we came from. We went back to our lodging. That night my father died from heart failure.

Mama found a Bukhara Jew 25 to bury my father at the Jewish cemetery according to the ritual. Bukhara Jews are different from European Jews, but they observe all the traditions. Mama gave this Jewish man her wedding ring and my father’s ring. He looked at Mama and gave her a bag of rice without saying a word. My father’s body was loaded onto a donkey-drawn cart. Mama and I followed the cart. After my father was buried, I took a handful of earth from his grave. I still keep it.

Mama was also exhausted and couldn’t go to work. She had trophic ulcers and unhealing sores on her skin. Our acquaintance helped me to get a job at the silkworm factory treating pods. I was to segregate male and female pods. Every day the walk to the factory was more and more difficult. I was almost fainting from starvation.

A miracle rescued us. Mama never gave up looking for my father’s sister Taube. We lost her in Velikiye Luki. One day we finally received a note from the evacuation center indicating that Taube was in the village of Topory, Kirov region [800 km north-west of Moscow]. Mama wrote to her, and my aunt replied that she was waiting for us and that we had to hurry up to get to the village before the Tavda River froze up. This was the only way to the village. Mama and I went there immediately. We took a barge to the village.

My aunt was staying with our distant relatives working in the hospital. They were working and received food cards. They were scared seeing how exhausted and starved we were. They were afraid we were not going to make it. Our relative, who was a doctor, told us to eat little food at a time, but allowed us to eat more often. This was difficult. I felt like eating a whole bucket of potatoes! We stayed with them.

Mama knitted clothes. Her customers were women in evacuation. They paid her with flour, cereals and butter. Having a better command of English, I went to work as assistant accountant at the fish factory. Labor army members 26, who were over the age to serve in the army worked there. Employees were paid their wages in fish. The chief accountant was Nadezhda, a woman of German origin 27 from Povolzhiye, who was in exile in the village. She liked me a lot. I learned my duties well, and it didn’t take long before I could work independently.

Shortly afterward Nadezhda retired. She insisted that I became her replacement. I received a room in the office building and was also given a plot of land. Mama moved in with me. We learned gardening, planted potatoes and had good crops. I fetched water from the river. The factory also provided wood to its workers. It was hard to cut huge logs with a wood chopper. It got stuck in a log, and it took me quite an effort to get it out. Later the director ordered that workers cut wood for me. I received fish every week and we were also given bread cards. Mama’s knitting provided additional food. We didn’t starve any longer.

In 1944 we heard that Latvia was liberated. Mama wrote letters to our relatives, but there was no response. The letters returned and were stamped ‘Undeliverable.’ We believed that they were still in evacuation. It never occurred to us that all of our kin were killed. In June 1945 we returned home. This was when we heard that Fascists killed our relatives during evacuation, though I don’t know whether these were Germans or Latvians, who killed them. Latvians started killing Jews even before the Germans came. They said they even reported to the Germans on the Jewish families they were friends with. I cannot understand what these people were driven by.

Almost all of our kin were killed. My father’s sister Slove Dubin’s family failed to evacuate. They were taken to the Riga ghetto 28. They were killed in the Rumbula wood 29. Only their older son Zalman survived. He went through all circles of hell. He was sent to a labor camp. Then he was taken to the Kaiserwald camp 30 in Riga, from where he was taken to Auschwitz. He was liberated by the Americans. [Editor’s note: Auschwitz was not liberated by American troops but by the Red Army in January 1945. It is possible that the interviewee means Buchenwald, which was liberated by American troops.] After the liberation he went to Israel. Recently Zalman visited his homeland and relatives. Mama’s parents and her sister perished in Liepaja. Mama’s sister Rosa Hodes, her husband and daughter Esther perished in the Riga ghetto. Mama’s brother Yakov and his family perished in Tallinn.

Mama’s brother Elias, or Grisha, was an officer in the Latvian division 31 at the front. He survived, but he also had hard times. Once after a battle soldiers were sitting round the fire and Grisha started telling them about how good life had been before the Soviet regime. One of them was a SMERSH 32 officer. He tore off Grisha’s shoulder straps and arrested him. The military tribunal sentenced him under art. 58 [It was provided by this article that any action directed at upheaval, shattering and weakening of the power of the working and peasant class should be punished] to ten years in a Gulag camp far in the north as an enemy of the people 33. Mama corresponded with him and sent him parcels every now and then. He had a hard life.

In 1953, after Stalin’s death, Grisha was rehabilitated 34, but he wasn’t allowed to return to Riga. He lived in Saldus, a small Latvian town. Grisha was a talented engineer. He went to work and met a nice Russian lady, who was chief accountant. They moved to Rezekne [200 km from Riga]. After Grisha returned from the Gulag he was very ill. He was mercilessly beaten by other prisoners and the staff in the camp. He told us that violence towards political prisoners was considered to be an expression of patriotism in the camp. Grisha had his kidneys and lungs injured in the camp. He also suffered from the cold. He died in the 1960s. He was buried at the Jewish cemetery in Rezekne.

Mama, Taube and I were thinking of moving to Riga. There was nobody waiting for us in Ludza. In Riga I could continue my studies and also, it was easier to find a job there. However, in the re-evacuation agency in Riga we were told that it was better for us to go back to where we had evacuated from. Of course, many people ignored this direction, but Mama was very honest and obedient, and would have never dared to disobey.

After liberation

We went back to Ludza. Our house was still there, but there was a family living in each room. They made room for us. I worked as an accountant at the industrial enterprise, and Mama earned her living by knitting. Mama insisted that I continued my studies. One year later I went to Riga where I entered the Technical School of Light Industry, taking into account that they had a dormitory where I could stay. There were two faculties: the Shoe and the Textile Faculty. The Shoe Faculty was Russian, and the Textile Faculty was Latvian. Somehow I believed that the Shoe Faculty taught shoemakers, and decided for the Textile Faculty. I passed my entrance exams easily. There were no prejudices against Jews at the time.

The dormitory was a shabby wooden house with no running water or toilet. There was an Orthodox church across the street from the dormitory, and we used their toilet. We fetched water in buckets. It was impossible to live on the stipend. Mama couldn’t afford to send me money. After classes I worked part-time as a typist in the Institute of Astronomy. I worked till midnight and left the typed pieces with the guard. I typed in Latvian. I also typed minutes and sheets for a shop. I slept little and ate little, but I studied very well and could also afford to support Mama.

There were Russian and Latvian students in the dormitory, but I never faced any anti-Semitism. I got along well with all of them. I finished my school with honors and before getting a job assignment 35 I was offered to go to the Leningrad College of Light Industry. This was a very tempting offer, but I was reluctant to leave Mama alone for so long. I wanted to stay in Riga.

I got a job assignment at the sewing factory. I worked as a shift forewoman in the sewing shop. I also received a small room - eight square meters - in the attic with no heating, gas or water. The front door of the room led to the staircase. There was a wood-stoked stove in the kitchen. However, this was at least some lodging. I convinced Mama to move in with me. Taube stayed in Ludza. She didn’t want to move. Taube died in Ludza in 1955. Mama had poor sight. The staircase was very steep, and she had to make a strong effort to climb it, but we were happy to be together. We accepted life as it was.

We observed Jewish traditions after we returned from the evacuation. The Soviet regime struggled against religion 36, but we didn’t think about it. We had Jewish traditions in our blood. Of course, we couldn’t follow the kashrut according to all rules, but we tried our best. We also celebrated Jewish holidays and tried to have traditional Jewish food on our table, even if we had to replace gefilte fish with potato pudding. We always had matzah on Pesach.

At the factory I received offers to join the Party several times, but I knew that being a party member I would have had to participate in party activities, and so I refused telling them that I was not ready to join the Party yet. Later I had another job and had no more such offers.

In 1948 anti-Semitism was brewing in the air. Processes against cosmopolitans 37 began, and it was clear that all cosmopolitans were Jews. Since cosmopolitans were enemies of the people, this meant that all Jews had to be watched closer to know what they had on their minds. Many Jews were fired. It was difficult to find another job. Nobody wanted to employ Jews. Fortunately, it didn’t affect me. My colleagues had a friendly attitude toward me. I’ve never kept my Jewish origin secret, and I’ve never wanted to change my Jewish name of Hana to a Russian name. If somebody addressed me with ‘Anna,’ a Russian name, I corrected this person saying my name was Hana. There were also talks that Jews had never been at the front holing up in Tashkent, Central Asia, though everybody knew that many Jews served at the front in the Latvian division.

The establishment of the state of Israel was a great joy for my mother and me. We knew that since Jews had their own state, we were under its protection no matter where we resided. We were happy that this ancient dream of our nation to restore their state came true.

In 1953 the Doctors’ Plot 38 started. I didn’t believe that Jewish doctors would poison Stalin, but some people did. Every day the radio broadcast the latest on Stalin’s health condition. It was clear that he was dying, and I prayed every day for his health. When on 5th March 1953 the radio announced his death, I cried like everybody else. I thought this was the end of the world and that we would never manage without Stalin. Of course, I didn’t know what was actually going on. Only later we learned that Stalin’s death saved Jewish people from a terrible ordeal. We didn’t know that there were trains prepared to take Jews to Siberia. When Khrushchev 39 spoke about Stalin’s crimes at the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU 40, I felt like everything I believed in had crushed. However, life went on. People were returning from exile, and what they were telling us was even more frightening than what Khrushchev had disclosed.

Marriage and children

I got married in 1953. I met my future husband Aron Rayzberg at the factory. He came to work as a foreman assistant at the shop. We decided to get married after we’d known each other for under two months. We lived a long and good life together, despite its hardships and difficulties.

Aron came from Korosten, Zhytomir region, Ukraine [150 km west of Kiev]. Aron father’s name was Moisey Rayzberg. His mother’s name was Basia. Basia was a dressmaker. Moisey owned a bakery. The Soviet regime nationalized this bakery, and he worked as a baker there. They were poor, but all their children went to school. They had six children, but three died in infancy. Three survived: Isaac, Aron’s older brother, Aron, born in 1928, and their younger sister Ida, born in 1929.

Their family was very religious. During the tsarist regime the Zhytomir area was within the Pale of Settlement, and the Jewish population was numerous before the war. The Jewish community had synagogues, cheders and raised their children in the Jewish way.

Aron’s older brother perished at the front in Belarus during the war. He was buried in a common grave. I wrote requests to various recruitment offices, and one day I received a response that Isaac Rayzberg had perished as a hero fighting for his Motherland. There was also the location of his grave indicated in this letter.

Aron, Ida and their parents were in the evacuation. After the war they returned home. Korosten was ruined. There was no place to live or a job. Their relatives had moved to Riga. Aron’s cousin Semyon Rayzberg was at the front in Latvia. He participated in the liberation of Riga, and moved to live there after the war. They were very hard up. Aron worked as a founder, before he fell ill with silicosis, and doctors advised him to change his job. Aron finished a technical school. He was responsible for equipment and devices at the factory. Aron was well respected at work.

Ida got married. Her marital name was Lipschiz. Ida had two children. She moved to Israel with her family, when mass emigration started in the 1970s. Ida died in the 1990s, and her children still live in Israel.

We had a traditional Jewish wedding. Of course, we couldn’t go to the synagogue. Aron was a party member and a shop party unit leader. There was a chuppah set up in my husband’s parents’ home. Our mothers cooked the wedding dinner of traditional Jewish food. Aron moved in with us after the wedding. Our son was born in 1954, and there were already four of us sharing this little room in the attic.

I wanted to name my son Mikhail, Moisey, after my father, but Aron’s father’s name was also Moisey, or Moishe, and it is against Jewish tradition to give babies the names of living relatives. This is a prejudice: they think that since the name has been given to a successor, the predecessor can leave this world. So we gave our son the name of Leizer, and he is Lazar in his documents. According to the tradition, the brit milah was performed on the eighth day. We invited a rabbi from the synagogue and a man to do the circumcision. It goes without saying that we kept this all a secret. I was very concerned about any possible infection that my son might get and even left the room to avoid seeing the process. However, everything went well, and the baby was healthy and strong.

Life was hard. If it hadn’t been for Mama, I don’t know how I would have managed. The maternity leave was 30 days and I had to go back to work. Mama brought my son to the factory for me to breastfeed him. This was particularly difficult for her to do in winter. We had no pram, and she had to carry the baby wrapped in a heavy blanket all the way to the factory. In summer we rented a little wooden hut in the suburb of Riga. My son spent all day in the garden. Mama took care of the baby till we came home from work. The only disturbing thing was that there were many rats, running through the house at night. At times my husband had to get up in the middle of the night to chase away the rats.

Before my son was born I was offered a job at the Ministry of Light Industry. There were the Ministry representatives visiting the factory, and I interacted with them. However, I was reluctant to go to work at the Ministry. I didn’t like paper work or generation of reports. I refused several times, but when another offer came, I agreed. The Ministry was located across the street from our house, while the factory was quite at a distance. Working at the Ministry I had more time to spend at home, and also, could drop by home during lunch to help Mama. I also studied at the extramural department of the Leningrad College of Light Industry and obtained a diploma. I worked 42 years at the Ministry and retired in 1981.

It took me some time to get used to the work at the Ministry. I liked working with people, and didn’t like paper work. However, I was a decent employee at the Ministry. Even those of my colleagues, who had a less than favorable attitude towards Jews, valued and respected me. I had two negative features, being a Ministry employee. Firstly, I was Jewish, and secondly, I wasn’t a member of the Party. However, through my work experience I had eight different bosses, and they had no problems with my performance. No staff lay-offs ever affected me, just because I was the best employee.

There were other Jews at my work place. Russian and Latvian employees were promoted to managers, and their Jewish colleagues stayed in the shadow. Our managers had Jewish assistants, who were smart and good. Jews knew that due to ‘Line item 5’ 41 they had no hopes of being promoted to managers, but they had to work anyway.

When I turned 55, and it was time to think about retirement, I got a job offer from my factory. If I had accepted this offer, I would have received a higher pension since it would have included bonuses and other allowances. However, I was used to the Ministry and I was reluctant to change jobs. In the late 1970s I received a three-room apartment in the new house that the Ministry built for its employees. We were very happy to get it.

We continued observing Jewish traditions in the family. Though my husband was a party member, he had grown up in a religious family, and he respected traditions very much. We had to celebrate Jewish holidays in secret, but my husband’s parents didn’t conceal their religiosity. Every year my mother-in-law went to visit the grave of a rabbi in a small town - I have forgotten its name - in Zhytomir region. This was considered to be a holy place, and many Jews went there for a blessing. They were poor and had to save for a year to pay for the trip, but she never missed one trip.

Basia was truly religious. When it wasn’t possible to buy matzah for Pesach, she baked it for the rest of the family in her own stove. At Yom Kippur she bought live chickens at the market and we visited her for the Kapores ritual. When she occasionally failed to buy chickens, we conducted the ritual with money. On Sabbath she walked to the synagogue, though it was quite a distance from home. Our house was across the street from the only synagogue in Riga. On holidays the whole street was filled with people.

My husband and I couldn’t visit the synagogue, so we observed Jewish traditions at home. I always fasted at work, and explained to my colleagues that I wasn’t feeling well. We also celebrated Soviet holidays after my husband moved in with us. We celebrated Victory Day 42, which was a really great holiday for us. The rest of the holidays were just additional days off for us, when we could spend more time with the family and visit our relatives.

We spent vacations near Riga. Occasionally we visited my husband’s family in Korosten. I remember our first trip there. We were walking along the street to his house, and children were running ahead of us shouting, ‘Arele and his wife are here!’ We enjoyed a wonderful reception. They were very nice and hospitable people. We stayed in Aron’s relatives’ house. There were long tables under cherry trees in the yard with plenty of Jewish food on them. Neighbors came to meet us, and they all were invited to sit at the table. However, Ukrainian Yiddish was a little different from that in the Baltic countries, but we understood each other well. We became friends. Sometimes Mama and little Lazar spent a whole summer in Korosten. There is nobody left in Korosten now. They moved to Israel in the 1990s.

I often went on business trips. Most of them were to Moscow and Leningrad. I noticed that the way Jews felt there was very different from how they did in Latvia. When we had visitors from Russia, they were surprised to hear people speaking Yiddish in the streets, while this was quite natural for us. There were many Jews in Riga at the time. Jews also held some leading positions. There were also anti-Semites, but I think, they were mostly those, who moved to Latvia after the war. Anyway, there were fewer anti-Semites than in Russia or Ukraine. Young people from other republics of the USSR came to the Baltic republics to enter higher educational institutions.

In the 1970s many Jews moved to Israel. My husband and I didn’t consider departure. I don’t like any changes, even the ones that are for the better. However, I sympathized with those who decided to move to Israel to live in their own country. Many of my friends have left. I couldn’t correspond with them at the time for the fear of losing my job. However, they wrote to my mother-in-law and we kept in touch this way. When my acquaintances visit her from Israel, Germany or the USA, they wonder why I’ve stayed. Anyway, I am here. Here is my home, and here are the graves of my dear ones.

My son went to the school near where we lived. He was very good at school. He was particularly good at exact sciences. When he finished the sixth grade, his teacher advised him to go to the mathematical school. It wasa Latvian school with advanced study of physics and mathematics, and it was the only school of the kind in the town. My son went to this school. The majority of students were Jewish children. At the beginning my son had to spend much time on his studies, but gradually the situation improved. He finished the school with honors. After finishing this mathematical school Lazar had no problem with entering the Polytechnic College. He studied at the Faculty of Mechanics.

My son was a good student. He completed his diploma work at the military plant. The plant management liked him a lot and forwarded a request to his college to assign him to this plant upon graduation. However, the Ministry didn’t approve the request for a Jew to work at the military plant. My son’s diploma tutor told him this was the only reason for non-approval. Lazar went to work at the railroad carriage building plant. It was located not far from home, and the atmosphere there was good. The majority of the employees were Jewish. They had a good attitude toward my son.

Lazar got married when he was a student. His wife is Russian, and my husband and I were very much concerned about it. However, we didn’t make any difficulties for them knowing that if we insisted, our son would leave her. But we also knew that if his life with another woman went wrong, he would blame us for his misfortunes. We understood that we couldn’t interfere with them. Fortunately, my son has a good wife and a good family. They have three sons. Mikhail was born in 1979, Yevgeniy was born in 1987, and Alexandr was born in 1988.

Mikhail finished a Jewish elementary school. I insisted on it, emphasizing on the closeness of the school to where they lived. Lazar’s wife didn’t have any objections to this. Mikhail studied well, but my son didn’t like the fact that there was no homework given to children and that there were few attendance days due to Soviet or Jewish holidays, or visitors from Israel or the USA, and the children were released from school again. Lazar was concerned that his son wouldn’t be trained to work and study discipline. He sent Mikhail to the gymnasium. Our grandson meets with his friends from the Jewish school.

When it was time for Mikhail to obtain his passport, he said he was going to have his Jewish origin indicated in the passport. This was very important for me, but I was concerned that my daughter-in-law would be against. She didn’t interfere, though. She said this was to be Mikhail’s choice. Our younger grandchildren also identify themselves as Jews, though the relevant line item has been removed from their passports. Both of them study in the gymnasium.

Mikhail completed a Masters at the Riga College of Transport Engineers. He specializes in computer engineering. His wife Yelena also finished this college. She is an economist. Their daughter Yulia is three.

My husband died in 1985. He felt ill in a tram all of a sudden, but the other passengers didn’t pay attention to him. When somebody finally noticed that there was something wrong with him and called the ambulance, it was too late. This was such a tragedy for me! We buried my husband at the Jewish cemetery.

There was only me and my elderly blind mother left. If it hadn’t been for Mama, I would have died from grief and loneliness. She had a strong will. She supported me and didn’t allow me to cry. Mama said that if I kept crying, it would be wet for Aron to lie in the ground. However, she also grieved and kept saying that she should have been the one to die. I only lived for the sake of Mama. She was completely blind and helpless, and I had to take care of her. Mama died in 1989, one month before turning 90. Her grave is beside my husband’s grave at the Jewish cemetery in Riga.

Recent years

When perestroika began, I liked what Mikhail Gorbachev 43 was doing. I was sorry that my husband had died before the time, when Jews could go to the synagogue and celebrate Jewish holidays freely, when it was no longer judged as a crime and anti-Soviet activity. It was allowed to correspond with people abroad and travel to different countries. Newspapers and TV and radio programs became interesting. I knew that it was no longer important for me, considering my age. My life was over, but I was happy for my son and grandchildren. It was good for them, no doubt.

The Jewish life was revived during perestroika. The Jewish community of Latvia was re-established, and also, the Latvian Association of Jewish Culture, LAJC 44, was opened. There was a Jewish family living nearby, and we were friends. They were going to emigrate, but they told me they wouldn’t move till they had taken me to the community. I didn’t feel like going anywhere, and they put me on the community list themselves. Volunteers started visiting me. I realized that somebody needed me and remembered about me, and this is very important for me, particularly after my mama died and I am absolutely alone. I began to regain my senses. I visit the community and have many acquaintances and friends there. This is my second home now.

I feel a bit sorry about the breakup of the USSR [in 1991]. This was a great state, and life was much easier than it is nowadays. When Latvia gained independence, life became more expensive. Pension is not sufficient to cover all needs. I remember life in Latvia before it was annexed to the USSR, and I hope that life will improve. I will not live that long, but it will be good for my son, my grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Their life has already changed and they are used to being free. Actually, one has to learn this as well.

Our Jewish choir is 15 years old, and all these years I’ve been its monitor. I remember how it all started. About ten of us got together in a park and started recalling the Jewish songs of our childhood. Someone had an accordion and started tuning up and playing quietly. We were recalling the forgotten songs by words and lines. A hooligan approached us yelling some anti-Semitic crap at us. We left the park and went to the LAJC where we stayed in the hallway. Hana Finkelstein, the chairman of the charity center, saw us there and suggested that we rehearsed in the center. She gave us shelter and supported the choir.

The center purchased costumes for our performances. We began to collect songs and music and also searched for people that wanted to sing in the choir. It was difficult in the first two years, but then our choir started growing and the repertoire was quite significant. My friends from Germany, Israel and Canada have sent me songs and notes. We rehearse a lot and tour Latvian towns that have a Jewish population.

The participants of the choir are old and ill, but when they sing you only see inspiration on their faces. They sing with their hearts, not with their throats. There were a number of men in the choir, they were beautiful soloists. There are few left: some passed away, and the others emigrated. However, we have newcomers, and our choir is alive. And, I guess, it will live on.

We are like a family. We celebrate birthdays and Jewish holidays. We recently celebrated the 85th birthday of Miron, our conductor. It was a nice party. Miron liked it. We live in different areas of the town, but we talk on the phone every day. I could never imagine that I would gain so many close people at my old age, when people usually only lose their dear ones.

I wouldn’t say I’m religious, but I pray every day. I didn’t remember the prayers of my childhood, but I have a prayer book for children, and it helps me to recall them. Every morning I thank the Lord for giving me another day, that I am healthy, can get out of my bed and talk to friends. Before going to bed in the evening I thank Him for the past day and that it was a good day. I pronounce the words of prayers in Hebrew and I understand what I am saying. I believe this helps.

Glossary: