Dupnista

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Dimitar Bozhilov

Date of Interview: July 2005

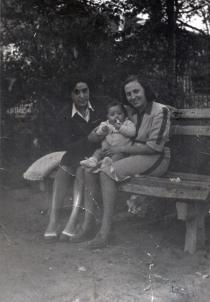

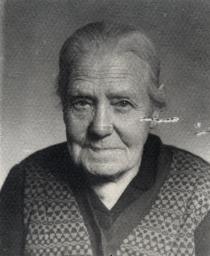

Ida Alkalai is a very polite, hospitable and warm, elderly lady. Her home is modestly furnished and is located on the central street of the town. She likes doing housework and is pleased with the recent renovation of her kitchen. She’s very attached to her family and relies on her husband’s opinion. She thinks that old people shouldn’t meddle into the lives of their children unless the children need it. Some years ago both her children left for Israel and her husband and she are very sad about it and are thinking whether they should follow them.

I come from the Sephardi Jews 1, who were banished from Spain in the 15th century 2. My mother’s family is from Kyustendil. My maternal grandfather’s name was Estrel Elazar and my grandmother’s name was Sara Elazar. My grandfather was a tinsmith and had a workshop in Kyustendil. My grandmother was a housewife. They were nice and modest people. We spoke with them in Bulgarian and Ladino 3. I can speak Ladino. I saw my maternal grandfather very rarely. I don’t remember him very well because he died when I was very young.

After my maternal grandfather died, every year my grandmother came from Kyustendil to spend two to three months with us so that she wouldn’t be alone. She lived by herself in Kyustendil. She was a talkative and easygoing woman. Unlike her, her sister, whose name was Reyna, was very strict and aristocratic. She wasn’t very talkative and looked very serious. I’ve vague memories about them from the time of my visits to Kyustendil. My grandmother was a little bit stooped and wore a kerchief, under which she had a braid. When I was a child, I visited my grandmother almost every year. I traveled by bus. Kyustendil was a beautiful town with nice mineral water spas. There were rich and very poor Jews living there. I usually visited my mother’s brothers and sisters when I went to Kyustendil on my summer vacations. I was still a pupil then. I had a very good time. We went to restaurants and had walks around the town. They asked me to sing and I did gladly.

My mother, Matilda Shekerdjiiska, was born in Kyustendil. She had three brothers and two sisters. The eldest one, Nissim Elazar, was a cobbler in Kyustendil. I don’t remember his wife. My mother’s second eldest brother was Estrel Elazar. He was a tinsmith in Kyustendil. His wife’s name was Vintura. They had four children, who left for Israel during the mass aliyah 4. They were very beautiful girls. I remember the names of two of them: Marika and Sarika. My mother’s third brother was Rahamim Elazar. He worked as a tailor and lived in Sofia. His family also left for Israel. I don’t know any details.

My paternal grandfather’s name was Haim Shekerdjiiski, and my grandmother’s name was Kadena Shekerdjiiska. My grandfather was related to Emil Shekerdjiiski, but I don’t know their exact relation. [Shekerdjiiski, Emil Mois (1912-1944): journalist, writer, literary critic. Born in Dupnitsa. A communist functionary and member of the Bulgarian Communist Party since 1932. Studied at ‘Kliment Ohridski’ Sofia University, as well as architecture in Belgrade (Serbia). Contributor to a number of Bulgarian newspapers and magazines. During World War II he was a partisan (with the nickname Stefan) in the Kyustendil squad. Killed as a partisan in a firing with the police in 1944.] I’m not sure where they were born, most probably in Dupnitsa. We never spoke about that. I only remember that four families in addition to my grandparents lived in the house in Dupnitsa, in which I was born. Apart from my father, the families of some of my father’s brothers also lived there.

When I was a child, probably at the end of the 1920s, my paternal grandparents left for Gyurgevo near Sapareva Banya, which is about 20 kilometers from Dupnitsa. My grandfather had a grocery store there. He sold everything: sugar, oil, flour, butter, ironware. Sapareva Banya is a resort village with a nice mineral water spa. Once, my grandfather decided to try the mineral water spa in Sapareva Banya and a bull passed through there, attacked and stabbed him. That’s how my grandfather died.

My grandfather liked his grandsons more than his granddaughters. He didn’t like me much because I was a girl. He didn’t pay much attention to me. He was a strict man. He was also quite a big man. He dressed in plain town clothes: he usually wore trousers and a jacket. I don’t remember him having a beard. After my grandfather died, Grandmother Kadena came to live with us in Dupnitsa. She lived alone in a room in the attic. She was a humble and short woman. Sometimes she had lunch with us or with some of my father’s brothers. I remember that she often sat on the big balcony and spent her time there.

My father’s name was Zhak [Haim] Shekerdjiiski. He was a dealer of second-hand clothes and goods. He had a small warehouse behind the house. He sold his goods there. He didn’t have a shop. My mother helped him. Villagers came and bought what they needed. They knew him and asked for him. That helped us during the time of the anti-Jewish laws, when Jews were forbidden to do business 5. Despite the bans the villagers continued to buy goods from us. We weren’t poor. My father went to Sofia every week and brought us nice food. But that was before the war [World War II]. After that my father got sick and stopped going to Sofia. We couldn’t afford to have a maid. My mother sewed custom-made clothes and my father’s business wasn’t too successful. We were a nice modest family. From my father’s brothers only Uncle Aron and Aunt Liza had a maid.

My father had five brothers and a sister: Buko, Aron, Adolf, Daniel, Nissim and Matilda. Uncles Aron, Adolf and Daniel lived in our yard. We were a very united family. Uncle Buko lived elsewhere and Uncle Nissim was in Sofia. Uncle Buko lived in the Jewish neighborhood. He had three sons: Haim, who was blind, Josko and Nissim. Haim was a basket-maker. All my father’s brothers were dealers. Uncle Buko sold flour. Uncle Nissim sold clothes in Sofia. Uncles Aron and Adolf also sold flour. Uncle Adolf went to Gyurgevo to help my grandfather, but after an accident he came back and became a dealer.

The eldest brother was Uncle Buko, and then my father was born. Aron was the third child, Nissim the fourth, Adolf the fifth, Daniel the sixth and Tanti [Aunt] Matilda was the youngest. She got married and lived in Sofia, but she didn’t have any children. Uncle Nissim’s wife was from Sofia. I don’t remember her name. Uncle Buko married Zumbul, nee Shimon, from Dupnitsa, Uncle Aron married Liza from Samokov, Uncle Daniel married Ester from Kyustendil, and Uncle Adolf married Vita, who was born in Sofia. Some of those families left for Israel. Unfortunately, I don’t remember the names of all my cousins and relatives. Uncle Daniel and Aunt Ester lived in Dupnitsa. They had two children: Rahamim, who became a professor in pharmacy in Sofia and Dinka, who became an accountant in Sofia.

There were a lot of Jewish houses in the center of Dupnitsa, but there was no Jewish neighborhood there. It was located not far from the center along the [Jerman] river 6, which passes through the town. There was no difference between the Jews living in the center and those along the river. You can’t say that those in the center were richer. We had a Jewish school called ‘Eliachi Hadjidavidov’ [Eliachi hadji David was a famous corn-dealer in Dupnitsa.]. The building of the Jewish municipality, the synagogue, which was massive and old, and the Jewish bank ‘Bratstvo’ [Brotherhood] 7 were in the center. The bank was governed by the Jewish municipality. It supported mostly Jews, and gave them credit for the purchase of apartments or education. Nissim Alkalai, my husband Aron Alkalai’s father, was a teller in that bank and was paying a mortgage there. We had a chazzan and shochet, who was in a separate building. Before the mass aliyah, after the state of Israel was founded [the big aliyah in 1948], the Jews in Dupnitsa were around 2000.

Our house had two floors and a big balcony. It was in the center of Dupnitsa, very close to the building of the Jewish municipality. It was built by Grandfather Haim. Each family had their own entrance. The house was old but the living conditions were good. There were two buildings in the yard. My family’s apartment was in one of the buildings and consisted of two rooms and a kitchen. We had water and electricity. We didn’t have a radio. One of the buildings faced the street and there were small shops on the ground floor. We lived in that building, but in the rooms facing the yard. The other building was further out in the yard. My father’s brothers, who lived in Dupnitsa, had separate shops with warehouses. All the shops were on the main street of the town.

My mother, Matilda Shekerdjiiska, nee Elazar, was born in Kyustendil. I suppose that my father saw her when he went to Kyustendil and that’s how they met. She worked as a seamstress. She had her own sewing machine. When I graduated from the vocational school, I started helping her with the sewing. She didn’t observe Sabbath because she had to work on Saturdays. I have seen her sew on Saturdays. But my grandmothers observed Sabbath very strictly.

My parents were humble people. They respected each other and loved us, the children, very much. My brother was also very modest. We never gave them much trouble. They weren’t very strict, but raised us warmly and lovingly.

My parents communicated mostly with Jews. Their environment was Jewish. They spoke more of Ladino than Bulgarian. In the past I heard people saying that Jews spoke Bulgarian with an accent. The interesting thing was that there were Bulgarians in the Jewish neighborhood who spoke Ladino. Their environment was Jewish, they communicated with Jews mostly and that’s how they learned Ladino. Some Bulgarians knew Ladino very well, because they had learned it when they were kids, during their games with the Jewish children. When I was a child, I was friends with all the children in the neighborhood, both Jewish and Bulgarian. We got along very well.

We had both Bulgarian and Jewish neighbors. During the Jewish holidays we welcomed our Bulgarian friends. Whole families came to visit us. My mother’s meals weren’t very different from the traditional Bulgarian cuisine, which includes a lot of vegetables and meat. But there were some differences, for example, Bulgarians didn’t make leak balls. My mother made very nice rice with chicken, okra with chicken, hotchpotch with aubergines and meat, pastries with cheese, minced meat, leaks, and spinach. She also made very nice crackers. My mother was a very good housewife. Grandmother Kadena also cooked very well.

All my father’s brothers got along very well. I saw my father and his brothers gather with friends and play poker. We were united. My mother gathered with her Jewish friends at home. I had a very good friend, Dinka, who was the daughter of Uncle Daniel. We played a lot along the river near the Jewish neighborhood. When we were a little older, I made her watch from the balcony whether Aron, my future husband, would enter the confectionery opposite the street so that I would go there to see him. Those were nice years. My husband and I met at a ‘jour:’ that’s how the gatherings of young people were called then. ‘Jours’ were for all young people, both Jews and Bulgarians. But my friends were Jews. ‘Jours’ were made in the houses. We listened to popular music and danced.

My husband and I flirted and grew closer to each other. We went out for about a year before we got married. We went together to restaurants and bars in Dupnitsa, but only after 9th September 1944 8. The synagogue was near our house. Jews visited it regularly. There was a small stream with drinking water in the yard. Weddings were also done there. My father didn’t go to the synagogue as he wasn’t religious. He liked doing the shopping. He was very good at housework and his business. Even during the greatest crisis in fascist times [during World War II] he managed to support our family. Every year we prepared winter supplies: raw and boiled pickles, flat sausages from mutton and pork. When I was a child, there was a small building next to the synagogue and we took hens there to be slaughtered by the shochet. But sometimes my father put on an apron and slaughtered the hen in the sink at home. Later when I got married, we asked someone from our Bulgarian neighbors to slaughter the chicken.

I studied in the Jewish school until the fourth grade. I think that there was also a nursery [cheder] at the Jewish school. It was for children up to pre-school age. We had a teacher at the Jewish school called Monsieur Revakh, who was very strict. He taught us Ivrit. When we didn’t know our work, he hit us with a small pencil and made us stand in the corner facing the wall. I wasn’t very good at Ivrit. Monsieur Revakh did his best to teach us the language, but I think we weren’t very hard working. There were also female teachers in the school who were Jewish. There was a stage at the Jewish school. We gathered in a big hall there to dance and party. The Jewish school was the only school in town which had a stage. On that stage I sang in the school choir.

Dupnitsa was a relatively developed town for its times. When I was a child there were carriages and buses to the nearby villages. I have traveled by carriage. There was a narrow-gauge line passing near Dupnitsa.

There were Jewish organizations in the town. The most popular were Maccabi 9 and ‘Saznanie’ [Conscience] 10. I was a member of Maccabi. I don’t remember doing gymnastics or any other sports. The association ‘Saznanie’ was a cultural and educational organization. There was a choir, library and theater group. They were all housed in the building of the Jewish municipality in the center of town. I also saw Bulgarians visit the ‘Saznanie’ community house. I don’t remember Maccabi having some concrete activities. We just gathered to see each other. Most of the Jews were members of ‘Saznanie.’ They had a rich cultural program. They put on opera performances, concerts and theater plays. They were much visited by the Jewish community in the town. You can say that the ‘Saznanie’ community house organized the cultural life of the whole town. My family also went to opera and theater performances.

When we were young, we often went to the theater and cinema. The movies were very popular and tickets were sold out quickly. The cinema was at the place of the military club in the center of the town. After my marriage we still went to the theater and cinema.

When I was a child, my parents and I often went on vacation by cart to Sapareva Banya. That is the village with the mineral water spa where my grandfather died. We usually spent 10-15 days there. My father hired a cart with a coachman; we took some luggage and went to Sapareva Banya. Usually only my family went, but sometimes we also took along other Jewish families. In Sapareva Banya we usually rented a private lodging during our stay. We did that once a year. Later, when I got married, my husband and I went to seaside resorts every year. I also often went to mineral water spa resorts.

When I was a child, we always celebrated Pesach and the other high Jewish holidays such as Frutas 11 and Chanukkah. On Pesach we weren’t allowed to eat bread. We strictly observed that for eight days. There was matzah and boyos [small flat loaves] on the table. We celebrated Pesach by ourselves. Usually some of my father’s relatives also visited us. My mother prepared a holiday dinner. We made burmolikos 12 from matzah. We put the matzah in water, then kneaded it, added eggs, and fried it in hot oil. We then dipped them in sugar syrup and ate them with a boiled egg. We also made pastel [pastry with meat]. We didn’t have separate dishes for Pesach, but before the holiday we cleaned the entire cutlery, and the house.\

When my father and uncles gathered at my grandfather’s for Pesach, the ritual was more closely followed. Firstly, they washed their hands, then said a prayer, and read the Haggadah. The observation of the rituals was done mostly by our grandparents. When I got married, my husband and I didn’t follow the Jewish rituals. After the mass aliyah in 1948-1950, not many Jews remained here.

On Yom Kippur, even nowadays, I observe the tradition of not eating anything from the evening of the previous day until 6pm the following day. I also do nothing on that day. On Frutas besides citrus fruit, my mother baked sunflower seeds, peanuts and hazelnuts. We all loved nuts at home and my father often bought them. On Purim we had small purses and went to our relatives who gave us coins. I went to my uncles and each of them put a lev in my purse. Children in fancy clothes also came and their parents gave them presents. There was a tradition on that day to give money to the children. That tradition is still being observed today. On Chanukkah there was a tradition for us to eat halva 13 and sweet things. The halva was made at home. We had a candlestick with eight candles and every day we lit a new one. Now we also have a candlestick for Chanukkah.

After three classes in a junior high school I enrolled in the vocational school in Dupnitsa. When I graduated from the junior high school, I wanted to study in a high school. Then my mother told me that I had to learn a craft and enrolled me in the vocational school. There I learned sewing and worked with my mother for some time. Sewing was what we did for a living. My mother sewed dresses and when I graduated from the vocational school I started giving her some advice. There were Jews and Bulgarians among my mother’s clients. I graduated with a master’s certificate in sewing. That was shortly before 1939. In school I didn’t have problems because of my origin. I remember that during the war [World War II] some Germans, civilians and military, were accommodated in the vocational school. I don’t know why. But they didn’t treat us badly.

At the beginning of the 1940s, when the anti-Jewish laws were adopted, we were very worried. My father continued working. He was close to a lot of villagers, who kept on buying goods from him. Otherwise, all the Jewish workshops, bank and organizations were closed. During the internment of Jews in 1943 14 in Sofia, a family of four came to live with us. That was the Kohen family. They were my mother’s relatives. We had a kitchen, living-room and one more room. We gave them the living-room. They stayed with us for some months.

From my father’s brothers only Uncle Daniel had a radio, a ‚Telefunken.’ During fascist times they hid it so that no one would see it. There was an order to confiscate all Jewish radio sets. We listened to the news on the war. During World War II, Uncle Rahamim, my mother’s brother, was interned from Sofia to Dupnitsa and lived at our place. I remember that he was with us during the bombardments. [On 13th September 1943 the British-American troops bombarded the Bulgarian towns Stara Zagora, Gorna Oryahovitsa and Kazanlak, as Bulgaria was allied with Germany. On 30th December 1943 they bombarded Sofia. In this air raid 70 people were killed and 95 wounded. The biggest air raid was in Sofia on 10th January 1944. 750 people were killed and nearly the whole city center was ruined]. He watched the planes passing through the sky and told me in Ladino that those were stars up there.

In January 1944 there were bombings in Dupnitsa. There were destroyed buildings. When we heard the sirens, we would all climb a hill near the town so that we wouldn’t get hurt. All the people from the town went there. As far as I know the American planes that went to Romania, I don’t know for what reason, didn’t throw their bombs, and when they were going back they threw their bombs over other parts of Bulgaria. It was good that they threw most of their bombs in the field. Before Uncle Rahamim came to us, he was in a labor camp in Kailuka 15 near Pleven. He was caught going outside during the forbidden hours and that’s why he was sent there. There was a fire at the place where the Jews were imprisoned and ten Jews died. My uncle survived. He lived in Sofia and died there.

When we weren’t allowed to go out, because we were being prepared for deportation 16, my father went out to sit for a while in front of the door. Then a fascist-oriented neighbor hit him and ordered him to go inside immediately. We weren’t allowed to go out even in front of our houses. There were shops with notices reading, ‘Forbidden for Jews.’ There were special shops for Jews. But we didn’t have notices on the doors of our houses. There were people in Dupnitsa who were against Jews even before the war. But most of the people supported us.

We got along very well with most of the Bulgarians. When we were about to be deported in 1943, all our belongings, everything which was stored for a girl who will get married such as sheets, towels, clothes, blankets, we gave to Bulgarians. But when they told us that we wouldn’t be deported, the Bulgarians gave us our belongings back. Then we had to stay in our houses and weren’t allowed to go out. Probably they waited for the trains to arrive to get us deported to the concentration camps.

The Aegean Jews, who were killed in the camps, passed through Dupnitsa 17. Some of those Jews spent a few days in Dupnitsa in some warehouse and the Bulgarians brought them food. I also remember that during fascist times Bulgarian friends visited my husband’s father to take him out to a friend’s house, when Jews were forbidden to go out after 8pm. He would take off the star [the interviewee means the yellow star worn obligatorily as a badge by Bulgarian Jews] 18 and they would hide him while walking on the street. During the war there was a curfew and we were allowed only to walk along the river.

On 9th September 1944 the partisans came to Dupnitsa from the Rila Mountain. I was at the square where a lot of people from the town had gathered. There wasn’t any fighting in the town, only the outright fascists were arrested and imprisoned. The authorities changed, the political prisoners were freed and we were very happy. There were speeches in the square.

My husband, Aron Alkalai, and I were very much in love. We have known each other ever since our adolescence. We had a large Jewish company. We got together and went to the cinema. We met at a hill near the town. He was very handsome and they called him ‘the baron.’ I was a very merry girl and sang very well. In September 1944 Aron went to the war front 19. He had enlisted as a volunteer. Then I gave him a lighter as a gift. Before that he had given me a bracelet. I had prepared my gift beforehand and hid it from my parents. Lighters were quite different then and we called them ‘tsigarnik’ [from ‘tsigara’ - ‘cigarette’ in Bulgarian]. I was very worried when Aron and my friends went to the labor camps 20 and after 9th September 1944, to the front. But the Jews in Bulgaria felt obliged to take part in the war against fascism and enlisted as volunteers. We got married in 1945. We only married before the registrar. I think that there were no religious weddings then. After we got married, Aron insisted that I shouldn’t work, so I stayed at home for some years. I did the housework and looked after our two children.

My husband was also born in Dupnitsa. He graduated from the vocational school in the town. He has a master’s certificate for a cobbler. His father, Nissim Alkalai, was a much respected man in the town. He worked as a clerk in the Jewish Bank until it was closed in 1940. His family members were very intelligent. His uncle, Mois Alkalai, was a headmaster and teacher in the Jewish school and the chairman of the Jewish municipality in Dupnitsa during World War II 21.

During the mass aliyah all my uncles left for Israel. That was the mass emigration of Jews from Bulgaria to Israel. My husband and I also wanted to leave. We did whatever my husband said. He didn’t want to leave because of his parents, because they had also decided to stay. It was very difficult to emigrate then because there was no one there to help you. You traveled by steamboat then. The people who emigrated packed their luggage in wooden boxes, so that they could use the wood to make sheds when they arrived. Now, with the help of relatives there, it’s much easier. It’s difficult to find a job in Israel, but it’s different from our times. Thanks to our older son, Nissim, our younger son, Zhak, managed to find a job. My father didn’t want to leave because of me, because my husband and I decided to stay. My parents also stayed in Dupnitsa and died here. Now my husband and I regret not leaving, because now we are alone without our kids, who are in Israel. We didn’t regret our decision earlier. We love Bulgaria and didn’t feel the need to emigrate. We often corresponded with our relatives in Israel. Now we keep in touch with my children by phone. The last time we visited Israel was four years ago.

In 1954 I started work in the Galenov Factory in Dupnitsa producing medicine. I started work when the factory was founded. My colleagues were very nice. Some of them were Jewish. The job wasn’t easy, we had quotas to fulfill.

I was respected at my workplace. I worked there for 21 years. It was later transformed into ‘Pharmahim.’ I retired from there with a small pension. I was easygoing and sang a lot. I was in the factory choir and had some solo performances in the community house of the town. I was also a soloist in the choir. I know songs in Ladino, which I learned from my mother.

After 9th September 1944 my parents stayed in the house where I was born. We continued to celebrate the Jewish holidays, but we didn’t get together with them, but with my husband’s family. My brother, Josko, often visited us. My uncles and aunts, who lived there, before they left for Israel, always got together on holidays.

My brother’s name is Josko Shekerdjiiski. He’s a little younger than me. He was born in 1927 in Dupnitsa. He also studied in the Jewish school. As a child he worked for my cousin, Haim Shekerdjiiski, with whom he made baskets. Then my brother graduated from a technical school, in food processing. After 9th September he started work in the shoe factory in Dupnitsa, where he worked until he retired. My brother’s wife is Olga who was born in Sofia. They have two children: Madlen [Madlena] and Zhak. Their family moved to Israel in the 1990s. The children were the first to go. Then they invited their parents. Zhak graduated from a technical school in communication equipment in Sofia and worked as a technician in Israel. Madlen is a nurse. My brother feels nostalgia for Bulgaria and visits Dupnitsa every year. But this year he and his wife aren’t in very good health and won’t come. Their children are happy in Israel. I think they went there for economic reasons.

After September 1944 we didn’t go to the synagogue, although it was opened. But after, most of the Jews immigrated to Israel from 1948 to 1950. It was then closed and used as some kind of a warehouse. Later, unfortunately, it was demolished and the Home of Techniques was built in its place. As far as I know the synagogue was built in 1599. I don’t know who made the decision to demolish it. The decision was made in Sofia. The Jewish organization in Dupnitsa didn’t stop working though.

After we got married, our two children were born: Nissim and Zhak. They weren’t raised especially in the spirit of the Jewish traditions, although after 9th September 1944 we continued to celebrate the Jewish holidays. You can say that they know the Jewish traditions well. We always celebrated Pesach. We lived with the family of my husband. His father read the Haggadah. The other holidays weren’t very strictly observed, probably only Yom Kippur, when we fasted. Our children don’t understand and can’t speak Ladino.

Zhak graduated from the Pedagogical Institute in Dupnitsa and was assigned to work as a teacher in Dalgopol [near Varna]. There he met his wife Zhechka, who is Bulgarian. They got married before the registrar. When he came and told us that he chose a wife from Dalgopol, my husband and I didn’t object. The parents of my daughter-in-law came to us in Dupnitsa and approved us as the family in which their daughter would live. My daughter-in-law is very nice. They have a son, Aron.

Our older son Nissim is an electrical technician and was promoted to director of a telephone technical office in Sofia. There he married Roza, who is Jewish. They married before the registrar and the next day they went by themselves to the synagogue and had a religious wedding. They have three children: Kristina, Ronit and Suzana.

Nissim immigrated to Israel about twelve years ago. He learned Ivrit very fast there. Now he speaks it fluently. Zhak also left with his family a couple of years ago. My older son emigrated mainly because his wife wished so. He had a good job in Sofia as a director. In Israel he now works as a supporting technician. His wife wanted to emigrate out of curiosity and patriotic reasons. My younger son emigrated due to economic reasons because his salary as a teacher was very low.

My children were raised among Bulgarians. There are no other Jews in the neighborhood, where our house is. My children got along with the Bulgarians very well. We got on very well with our neighbors both before and after 9th September 1944. We were also welcomed by them. We can’t complain about anything. Our environment was mostly Bulgarian. When our sons were born, we celebrated the brit milah. But we didn’t celebrate their bar mitzvah. My mother-in-law sang songs in Ladino and Bulgarian to my children. I also sang to them.

It’s difficult for me to comment on the political events in Bulgaria and abroad in recent years. Now life is more expensive, but people have more opportunities. Although our pensions are small, thanks to Joint 22 we can cover our expenses. What I think about are my children. They ask us to go live with them all the time, but we haven’t decided yet. We have prepared our documents, but at our age it’s very difficult to go to another country, in which we would understand nothing.

Now I do only housework. I spend my time mostly at home. Sometimes I meet with the women from the Jewish municipality in the Jewish club. We celebrate birthdays and Jewish holidays, mostly Pesach.

Glossary1 Sephardi Jewry

Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin. Their ancestors settled down in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, South America, Italy and the Netherlands after they had been driven out from the Iberian peninsula at the end of the 15th century. About 250,000 Jews left Spain and Portugal on this occasion. A distant group among Sephardi refugees were the Crypto-Jews (Marranos), who converted to Christianity under the pressure of the Inquisition but at the first occasion reassumed their Jewish identity. Sephardi preserved their community identity; they speak Ladino language in their communities up until today. The Jewish nation is formed by two main groups: the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi group which differ in habits, liturgy their relation toward Kabala, pronunciation as well in their philosophy.2 Expulsion of the Jews from Spain

The Sephardi population of the Balkans originates from the Jews who were expelled from the Iberian peninsula, as a result of the ‘Reconquista’ in the late 15th century (Spain 1492, and Portugal 1495). The majority of the Sephardim subsequently settled in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, mainly in maritime cities (Salonika, Istanbul, Smyrna, etc.) and also in the ones situated on significant overland trading routes to Central Europe (Bitola, Skopje, and Sarajevo) and to the Danube (Adrianople, Philipopolis, Sofia, and Vidin).3 Ladino

also known as Judeo-Spanish, it is the spoken and written Hispanic language of Jews of Spanish and Portugese origin. Ladino did not become a specifically Jewish language until after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 (and Portugal in 1495) - it was merely the language of their province. It is also known as Judezmo, Dzhudezmo, or Spaniolit. When the Jews were expelled from Spain and Portugal they were cut off from the further development of the language, but they continued to speak it in the communities and countries to which they emigrated. Ladino therefore reflects the grammar and vocabulary of 15th century Spanish. In Amsterdam, England and Italy, those Jews who continued to speak ‘Ladino’ were in constant contact with Spain and therefore they basically continued to speak the Castilian Spanish of the time. Ladino was nowhere near as diverse as the various forms of Yiddish, but there were still two different dialects, which corresponded to the different origins of the speakers: ‘Oriental’ Ladino was spoken in Turkey and Rhodes and reflected Castilian Spanish, whereas ‘Western’ Ladino was spoken in Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia, Serbia and Romania, and preserved the characteristics of northern Spanish and Portuguese. The vocabulary of Ladino includes hundreds of archaic Spanish words, and also includes many words from different languages: mainly from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, French, and to a lesser extent from Italian. In the Ladino spoken in Israel, several words have been borrowed from Yiddish. For most of its lifetime, Ladino was written in the Hebrew alphabet, in Rashi script, or in Solitro. It was only in the late 19th century that Ladino was ever written using the Latin alphabet. At various times Ladino has been spoken in North Africa, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, France, Israel, and, to a lesser extent, in the United States and Latin America.4 Mass Aliyah

Between September 1944 and October 1948, 7,000 Bulgarian Jews left for Palestine. The exodus was due to deep-rooted Zionist sentiments, relative alienation from Bulgarian intellectual and political life, and depressed economic conditions. Bulgarian policies toward national minorities were also a factor that motivated emigration. In the late 1940s Bulgaria was anxious to rid itself of national minority groups, such as Armenians and Turks, and thus make its population more homogeneous. More people were allowed to depart in the winter of 1948 and the spring of 1949. The mass exodus continued between 1949 and 1951: 44,267 Jews immigrated to Israel until only a few thousand Jews remained in the country.5 Law for the Protection of the Nation

A comprehensive anti-Jewish legislation in Bulgaria was introduced after the outbreak of World War II. The ‘Law for the Protection of the Nation’ was officially promulgated in January 1941. According to this law, Jews did not have the right to own shops and factories. Jews had to wear the distinctive yellow star; Jewish houses had to display a special sign identifying it as being Jewish; Jews were dismissed from all posts in schools and universities. The internment of Jews in certain designated towns was legalized and all Jews were expelled from Sofia in 1943. Jews were only allowed to go out into the streets for one or two hours a day. They were prohibited from using the main streets, from entering certain business establishments, and from attending places of entertainment. Their radios, automobiles, bicycles and other valuables were confiscated. From 1941 on Jewish males were sent to forced labor battalions and ordered to do extremely hard work in mountains, forests and road construction. In the Bulgarian-occupied Yugoslav (Macedonia) and Greek (Aegean Thrace) territories the Bulgarian army and administration introduced extreme measures. The Jews from these areas were deported to concentration camps, while the plans for the deportation of Jews from Bulgaria proper were halted by a protest movement launched by the vice-chairman of the Bulgarian Parliament.6 Jerman River

Dupnitsa is a town in Southwest Bulgaria. It is located at an important crossroads on the way from Sofia to Thessaloniki and Plovdiv – Skopje. The town is 535 m above sea level. It is in the Dupnitsa valley at the foot of the western slopes of the Rila Mountain and the southern slopes of Veria. The biggest river which passes through the valley is Struma. The river Jerman, which originates from the Seven Rila Lakes passes through Dupnitsa. The Jewish neighborhood in Dupnitsa is located near the Jerman River under the Karshia hill near Sharshiiska Street. Jews settled here as early as the 16th century. In fact, the river divides the Jewish neighborhood from the Bulgarian one.7 Jewish bank 'Bratstvo' [Brotherhood]

Co-operative bank 'Bratstvo' in Dupnitsa exists since 1st January 1925. It was officially registered on 12.12.1924 in the District Court in Kyustendil. Before that the association existed for many years under the name 'Dupnitsa mutual benefit association 'Bratstvo', but since it did not correspond to the law of co-operative associations, it was closed down and founded on the basis of the principles written in the law. A new statute was prepared, which was approved by the Bulgarian People's Bank. The object of the co-operative bank 'Bratstvo' was to help its members with an accessible credit in the form of three-month loans, saving accounts and other bank operations. The bank was governed by a board of directors, consisting of nine people; a director and an accountant. At the official registration of the bank Haim Alkalai was elected chairman of the board of directors and its members were Buko Leonov and Leon Levi. St. Hristov, a long-time teacher and clerk in the Bulgarian Agricultural and Cooperative Bank, was the director of the bank. The bank was housed on the second floor of the Jewish municipality in Ruse. Despite the large number of Jews in that bank, it was not a part of the Jewish municipality. It was subordinate to the co-operative association, whose goal was to give credits to its members, to arrange the transactions with its goods, provide machines and equipments for the development of crafts. The bank existed until 1947 when it was nationalized by law.8 9th September 1944

The day of the communist takeover in Bulgaria. In September 1944 the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria. On 9th September 1944 the Fatherland Front, a broad left-wing coalition, deposed the government. Although the communists were in the minority in the Fatherland Front, they were the driving force in forming the coalition, and their position was strengthened by the presence of the Red Army in Bulgaria.9 Maccabi World Union

International Jewish sports organization whose origins go back to the end of the 19th century. A growing number of young Eastern European Jews involved in Zionism felt that one essential prerequisite of the establishment of a national home in Palestine was the improvement of the physical condition and training of ghetto youth. In order to achieve this, gymnastics clubs were founded in many Eastern and Central European countries, which later came to be called Maccabi. The movement soon spread to more countries in Europe and to Palestine. The World Maccabi Union was formed in 1921. In less than two decades its membership was estimated at 200,000 with branches located in most countries of Europe and in Palestine, Australia, South America, South Africa, etc.10 'Saznanie' [Conscience]

a Jewish self-educational association. It was founded in Dupnitsa on 7th January 1902. Its founders were mostly members of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party. They were: Israel Yako Levi – a tobacco worker, Israel Daniel – a tailor, Moshe Alkalai – a tailor, Aron Luna – a merchant, Yako Yusef Komfort – a merchant. The goal of the association was to improve the culture and education of its members, help poor students with books, clothes and money. Another goal of the association was also the fight against nationalism and chauvinism of the Zionist organization, 'which poisons the mind of youths and strives to detach them from the class fight of the laborers.' The number of the members of 'Saznanie' reached 150 at one point. The leadership consisted of seven people – a chairman, a secretary, a treasurer, a cultural teacher, and three people as supervisory council. There were different sections in the association – a temperance one, a tourist one, a sports one with their own groups, which educated the members. The association in Dupnitsa had a library with mostly fiction and Marxist literature. There was also a choir, an orchestra and a theater group. The operetta 'Natalka-Poltavka' was staged in Dupnitsa, as well as the following plays: 'The High Laugh' by Victor Hugo, 'Intrigue and Love' by Schiller, 'The Barber of Seville' by Beaumarchais, 'The Victim' and 'The Dowery' by Albert Michael, 'Tevie The Milkman' by Sholom Aleichem, 'Les' by Ostrovsky, 'George Dandin' by Moliere. The members of 'Saznanie' such as Mois Alkalai, Kalina Alkalai, Mair Levi, who was the choir conductor, Buko Revakh, Roza Chelebi Levi were some of the best amateur actors. The main role in the play 'Tevie The Milkman' was performed by Mois Alkalai. Everyone admired his acting and the distinguished actor Leo Konforti (also of Jewish origin) was among his students. Some of the plays were performed in Judesmo-Espanol (Ladino), and the others in Bulgarian. The association was closed under the Law for Protection of the Nation. With its activities it contributed to the development of culture and education and left a permanent trace in the minds of the people in Dupnitsa.11 Fruitas

The popular name of the Tu bi-Shevat festival among the Bulgarian Jews.12 Burmoelos (or burmolikos, burlikus)

A sweetmeat made from matzah, typical for Pesach. First, the matzah is put into water, then squashed and mixed with eggs. Balls are made from the mixture, they are fried and the result is something like donuts.13 Halva

A sweet confection of Turkish and Middle Eastern origin and largely enjoyed throughout the Balkans. It is made chiefly of ground sesame seeds and honey.14 Internment of Jews in Bulgaria

Although Jews living in Bulgaria where not deported to concentration camps abroad or to death camps, many were interned to different locations within Bulgaria. In accordance with the Law for the Protection of the Nation, the comprehensive anti-Jewish legislation initiated after the outbreak of WWII, males were sent to forced labor battalions in different locations of the country, and had to engage in hard work. There were plans to deport Bulgarian Jews to Nazi Death Camps, but these plans were not realized. Preparations had been made at certain points along the Danube, such as at Somovit and Lom. In fact, in 1943 the port at Lom was used to deport Jews from Aegean Thrace and from Macedonia, but in the end, the Jews from Bulgaria proper were spared.15 Kailuka camp

Following protests against the deportation of Bulgarian Jews in Kiustendil (8th March 1943) and Sofia (24th May 1943), Jewish activists, who had taken part in the demonstrations, and their families, several hundred people, were sent to the Somovit camp. The camp had been established on the banks of the Danube, and they were deported there in preparation for their further deportation to the Nazi death camps. About 110 of them, mostly politically active people with predominantly Zionist and left-wing convictions and their relatives, were later redirected to the Kailuka camp. The camp burned down on 10th July 1944 and 10 people died in the fire. It never became clear whether it was an accident or a deliberate sabotage.16 Plan for deportation of Jews in Bulgaria

In accordance with the agreement signed on 22nd February 1943 by the Commissar for Jewish Affairs Alexander Belev on the Bulgarian side and Teodor Daneker on the German side, it was decided to deport 20,000 Jews at first. Since the number of the Aegean and Macedonian Jews, or the Jews from the 'new lands,' annexed to Bulgaria in WWII, was around 12,000, the other 8,000 Jews had to be selected from the so-called 'old borders', i.e. Bulgaria. A couple of days later, on 26th February Alexander Belev sent an order to the delegates of the Commissariat in all towns with a larger Jewish population to prepare lists of the so-called 'unwanted or anti-state elements.' The 'richer, more distinguished and socially prominent' Jews had to be listed among the first. The deportation started in March 1943 with the transportation of the Aegean and the Thrace Jews from the new lands. The overall number of the deported was 11,342. In order to reach the number 20,000, the Jews from the so-called old borders of Bulgaria had to be deported. But that did not happen thanks to the active intervention of the citizens of Kyustendil Petar Mihalev, Asen Suichmezov, Vladimir Kurtev, Ivan Momchilov and the deputy chairman of the 25th National Assembly Dimitar Peshev and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Before the deportation was canceled, the Jews in Plovdiv, Pazardzhik, Kyustendil, Dupnitsa, Yambol and Sliven were shut in barracks, tobacco warehouses and schools in order to be ready to be transported to the eastern provinces of The Third Reich. The arrests were made on the eve of 9th March. Thanks to the intervention of the people, the deportation of the Jews from the old borders of Bulgaria did not happen. The Jews in Dupnitsa were also arrested to be ready for deportation.17 Annexation of Aegean Thrace to Bulgaria in WWII

The Treaty of Neuilly, imposed by the Entente on Bulgaria after WWI, deprived the country alongside with its WWI gains (Macedonia) also of its outlet to the Aegean Sea (Aegean Thrace) that had been a part of the country since the Balkan Wars (1912/13). King Boris III (1918-43) joined the Axis in 1941 with the hope to be able to regain the lost territories. Bulgarian troops marched into the neighboring Yugoslav Macedonia and Greek Thrace. Although the territorial gains were initially very popular in Bulgaria, complications soon arose in the occupied territories. The oppressive Bulgarian administration resulted in uprisings in both occupied lands. Jews were persecuted, their property was confiscated and they had to do forced labor. Although the Jews in Bulgaria proper were saved they were exterminated in the newly gained territories. Over 11.000 Jews from the Bulgarian administered northern Greek lands (Thrace and Macedonia), mainly from Drama, Seres, Dedeagach (Alexandroupolis), Gyumyurdjina (Komotini), Kavala and Xanthi were deported and murdered in death camps in Poland. About 2.200 Jews survived.18 Yellow star in Bulgaria

According to a governmental decree all Bulgarian Jews were forced to wear distinctive yellow stars after 24th September 1942. Contrary to the German-occupied countries the stars in Bulgaria were made of yellow plastic or textile and were also smaller. Volunteers in previous wars, the war-disabled, orphans and widows of victims of wars, and those awarded the military cross were given the privilege to wear the star in the form of a button. Jews who converted to Christianity and their families were totally exempt. The discriminatory measures and persecutions ended with the cancellation of the Law for the Protection of the Nation on 17th August 1944.19 Bulgarian Army in World War II

On 5th September 1944 the Soviet government declared war to Bulgaria which was an ally to Hitler Germany. In response to that act on 6th September the government of Konstantin Muraviev took the decision to cut off the diplomatic relations between Bulgaria and Germnay and to declare war to Germany. The Ministry Council made it clear in the decision that it came into effect from 8th September 1944. On 8th September the Soviet armies entered Bulgaria and the same evening a coup d'etat was organized in Sofia. The power was taken by the coalition of the Fatherland Front, consisting of communists, agriculturalists, social democrats, the political circle 'Zveno' (a former Bulgarian middleclass party). The participation of the Bulgarian army in the third stage of World War II was divided into two periods. The first one was from September to November 1944. 450 000 people were enlisted under the army flags and three armies were formed out of them, which were deployed on the western Bulgarian border. Those armies took place in the Nis and Kosovo advance operations and defeated a number of enemy units from the Nazi forces, parts of the 'E' group of armies and liberated significant territories from Southeast Serbia and Vardar Macedonia. The second period of the Bulgarian participation in the war was from December 1944 to May 1945. The specially formed First Bulgarian Army, including 130 000 soldiers took part in it. After regrouping the army took part in the fighting at Drava – Subolch. In the end of March the Bulgarian army started advancing and then pursuing the enemy until they reached the foot of the Austrian Alps. The overall Bulgarian losses in the war were 35 000 people.20 Forced labor camps in Bulgaria

Established under the Council of Ministers’ Act in 1941. All Jewish men between the ages of 18–50, eligible for military service, were called up. In these labor groups Jewish men were forced to work 7-8 months a year on different road constructions under very hard living and working conditions.21 Jewish municipalities in Bulgaria during World War II

Ever since the liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in 1878, Jewish municipalities have been formed if there were 20 Jewish families in a town. The municipality was headed by a synagogue board, which took care of charity and religious matters. Its mandate was three years and it included 5-6 people. There was also a school board selected in accordance with the Law on Education and the municipality council. The specific thing about Jewish municipalities was that they were not only religious, but also answered the educational, cultural, national and social needs of the Jews. In Bulgaria in 1936 the Jewish municipalities were 33. The largest one was the Sofia one, followed by the Plovdiv one, the Kyustendil one, the Vidin one, the Dupnitsa one, etc. Most of the Bulgarian Jews are Sephardi-Spanish-Portugal Jews and Ashkenazim Jews from Western Europe. Both communities believe in Judaism. The Jewish municipalities were supported by: 1) a religious tax – araha; 2) fees for various services and rituals; 3) fees for the issuing of documents. In the period of World War II and more specifically after the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs was created in Bulgaria in 1942, article 7 of its statute says: ‘The Jewish municipalities are governed by the Commissariat on Jewish Affairs. The Jewish municipalities are governed by consistories, consisting of a chairman and 4-6 Jewish members, all of them appointed by the Commissar on Jewish Affairs. Each consistory has a delegate appointed by the Commissar on Jewish Affairs. The delegate can be an official. In Sofia there is a central consistory consisting of a chairman and six Jewish members and a delegate of the Commissar. The orders of the delegate are obligatory for the consistory; they can be appealed by the consistory in front of the delegate of the central consistory, respectively, in front of the Commissar on Jewish Affairs. The Jewish municipalities are defined and act in accordance with regulations and instructions developed by the council on Jewish Affairs.The task of the Jewish municipalities is to prepare the Jewish population for deportation. All Jewish non-profit initiatives such as synagogues, schools, charitable and sociable events for Jews, etc. are now under the supervision of the Jewish municipalities and their responsibility.’

In this way, from 1941 onwards with the adoption of the Law for Protection of the Nation and the Commissariat on Jewish Affairs, whose goal was to prepare the Jews for deportation, the function and the definition of the Jewish municipality in Bulgaria was changed. Before 1940 it had a social function, and after that it was used as an organizational structure implementing the anti-Jewish laws.