Pesse Speranskaya

Tallinn

Estonia

Date of interview: September 2005

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

I stayed in a hotel in Tallinn, and that was where I invited Pesse Speranskaya for this interview. Pesse and her husband Alexandr visited me on Sunday. I appreciated it that they had shifted their initial plans to meet with me. Pesse looks young for her age. She is slim and dressed to the fashion. Pesse has auburn hair, nicely cut and done. She’s very sociable and friendly. She’s very special about talking to people: few minutes later I felt quite like I was talking to a friend, whom I’d known for long. Pesse had to go through many hard things in her life: the war took away her childhood, she became an orphan, when she was very young, and her only daughter died, but she’s never given up. She’s always there to help, when she may be needed, and lift up somebody’s spirit, when it’s down.

The Soviet invasion of the Baltics

After the fall of the Iron Curtain

My family background

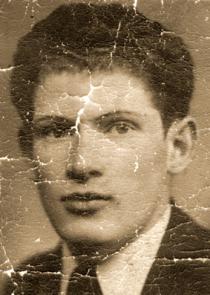

My father’s parents lived in Viljandi [about 130 km east of Tallinn], a small Estonian town. My grandfather Iosif Marjenburger, my grandmother Ella and their children were born in Viljandi. My grandfather was a tinsmith. He made buckets, pans, wash-tubs, buckets, etc. One a week he took his goods to a large market. His goods were in demand, and the family was well provided for. My grandmother took care of the children and housekeeping. The family had 13 children, which was many even at that time. I didn’t know the older children, and in our family, they never talked about them. They might have left for America or Palestine, looking for a better life. This was a common way many Jews undertook at the time. My father’s brother Max was the oldest of those, who stayed in Estonia. My future father Hermannn Marjenburger was born in 1914. After him his sisters Rebecca, Lina and Mary, his brothers Zalman and Leo and the youngest Bertha were born. It was difficult to support the family with so many children. My grandfather involved his sons in the tinsmith’s business as soon as they grew old enough to be of help to him. My father and his brothers were tinsmiths. As for the daughters, they were helping their mother about the house. All of the children were smart, bright, hardworking and handy.

My father’s mother tongue was Yiddish. The family spoke Yiddish, but they also spoke fluent Estonian. All residents of Estonia of whatever origin knew the official language of their country. My father’s parents were religious. I believe their generation was religious without exceptions. They strictly observed Jewish traditions, celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and went to the synagogue. It goes without saying that all of them followed the kashrut. As for their children, they were not so religious. They still observed Jewish traditions, but they only went to the synagogue on holidays. They did not spend so much time praying. Of course, there were exceptions to that, but I’m saying what it was like in general.

I don’t know what kind of education my father, his brothers and sisters received. I guess they must have studied somewhere. Perhaps, in a Jewish school. They could read and write, all of them, and my father liked reading.

I know little about my mother’s family. I don’t even know my grandfather’s name. He died in 1940, when I was just a little girl. My grandfather’s surname was Shajevich. My mother’s family lived in Tartu [second largest town in Estonia, 170 km east of Tallinn]. My grandfather and my grandmother Teresa Shajevich were born in Tartu. I don’t know what my grandfather did for a living, but I know that they were extremely poor. My mother didn’t tell me much about her childhood. I also know that they were starved at times. There were four children in the family. I have no information about my mother’s older brother. Mama didn’t tell me about him, and I don’t even know his name. My mother Hana, born in 1911, was the second child in the family. My mother’s sister Fanny, following my mother, was born in 1916. I don’t know, when Sonja, the youngest one, was born. My grandmother’s sister Rokhe-Leya also lived in Tartu with the Shajevich family. She was single.

My mother’s parents were very religious, and my grandmother was particularly religious. However poor the family was, my grandmother had crockery and utensils for eat and dairy products specifically. She also had a set of crockery for Pesach. My grandmother followed the kashrut. They always met Sabbath at home, and did no work on the day to follow. My grandmother and grandfather went to the synagogue on Sabbath and Jewish holidays, and they celebrated Jewish holidays at home in accordance with all rules. They spoke Yiddish and Estonian in the family. As for education they received, I know that my mother’s sister Fanny finished a Jewish gymnasium in Tartu. My mother also studied therefore some time, but she never finished it. Perhaps, the family didn’t have enough money to pay for her education. Her younger sister Sonja finished a Russian gymnasium.

My mother’s sister Fanny was a Zionist 1. She looked forward to moving to Palestine and help building up a Jewish state. She did go to Palestine with a group of young enthusiasts like her. This happened in 1933. Before 1941 my mother corresponded with her. Fanny took part in building up a kibbutz where she stayed to work. Se married a teacher from this same kibbutz. I don’t remember his first name, but his surname was Kharari. They had two children: son Robert, born in 1938, and daughter Miriam, born in 1943. Fanny wrote about her life and her family and sent pictures. I still have one. My mother’s second sister Sonja was single. She lived with her parents, and when my mother got married, she lived with our family.

My mother went to work for a store owner, when she was still very young. She had some training before she started working on her own. Mama was very committed to her job. A shop assistant was to use all his or her skills to make a customer buy something. Even if this customer just came in to look around and had no intention to buy anything initially, a good shop assistant would find out how to make him or her think that there is the thing he or she wanted to buy, indeed. Otherwise, if a customer leaves the store without a purchase once or twice, the store owner would doubt about his or her efficiency. However, my mother managed her job very well, and the store owner was very upset when she got married and had to quit her job.

My mama didn’t tell me any details about how she met my father, but what she did say was that they liked each other well from the very beginning. It didn’t take long before my father proposed to my mother. My father’s parents did not quite like the idea of this marriage. My father’s family was rather wealthier than my mother’s, and my grandfather Marjenburger did not think this was a proper arrangement from the family perspective. However, my father didn’t listen to his parents. They got married in Tartu, and my father left Viljandi for Tartu. They had a traditional Jewish wedding. Though my mother’s parents were poor, they did their best to arrange a good wedding party for my mother. After the wedding my mother and father rented a 3-room apartment with stove heating in Peek. My father was a tinsmith and my mother was a housewife.

Growing up

I was born in 1935. I was given the name of Pesse, and my full first name is Pesse-Sore. I have dim and fragmentary memories of my childhood. My mother told me many details, when I grew up. My father liked spending time with me. He liked playing with me. I remember how during our walks he used to hide away and I started crying from the fear that he got lost. I can still remember this childish fear of loosing my father. When I was born, my father bought a camera to take pictures of me, though this was an expensive thing to buy at the time. Unfortunately, these pictures were lost, when we evacuated. I loved my father dearly. I associated him with a holiday: walking, having ice-creams and playing games. Mama treated me more strictly than my father did. We were not quite wealthy, but we had sufficient food and clothes and everything we needed to live a decent life. My father pampered me. I had a sweet tooth, and my father brought me fresh cakes from the bakery round the corner every morning before going to work. I woke u in the morning, and there was a cake on my bedside board waiting for me. Each morning started from a little festivity. My father was a very kind and interesting person. He seemed to have attracted people. He had many friends and acquaintances.

I was a very independent girl. My mother told me that I already went to buy bread at the bakery, when I was 3 or 4 years old. My mother was watching me crossing the street from the window, and waved her hand to me, when I was on my way back. I can remember this.

My parents did observe Jewish traditions, but this was more a tribute to the public opinion rather than deep religiosity. They did it, because this was a common thing to do, and not because they felt like doing this. I don’t think we celebrated Sabbath at home. On big Jewish holidays my parents went to the synagogue. There was a large choral synagogue 2 in Tartu. It was visited by all Jewish residents of Tartu on Jewish holidays. Tartu was the second largest town in Estonia, and the Jewish community was numerous. There were many Jewish students in the Tartu University as well. In Estonia, even during the tsarist rule there was no Jewish admission quota 3 to universities. If intelligent young people could not afford to pay for their education, they could obtain support from the students’ foundation [the Jewish students’ foundation: established in Tartu in 1875. This was the first Jewish students’ organization in Estonia. Its initial objective was to provide assistance to Jewish students from poor families. Wealthier Jewish families made annual contributions to the foundation and the board of trustees allocated the funds to the needy students. In the 1930s Rector of the Tartu University noted the foundation for its efficient performance]. Public associations in Tartu often arranged students’ balls or charity events attended by all residents of the town.

We visited my mother’s parents to celebrate Jewish holidays. My grandmother made traditional Jewish food. She always observed the rules. She had special crockery for Pesach, which she kept in a particular cupboard. The family reunion included my grandmother, my grandfather, my grandmother’s sister Rokhe-Leya, our family and my mother’s younger sister Sonja. Sometimes we had some guests. There was a tradition in Tartu that if a visiting Jewish person had failed to go home on holiday and whatever circumstances forced him or her to stay, then he or she was invited to join a local Jewish family. My grandmother and grandfather used to have such guests every now and then. My mother’s parents treated my father well and loved and pampered me. I was their only granddaughter. The thing was, they could only enjoy the pictures of their daughter Fanny’s children. As for my father’s parents, there was some tension in relationships with them. Even when I was born, they did not visit Tartu to see their granddaughter. They could never forgive my father to have got married without having their consent.

In 1939 my mother’s younger sister Sonja got married. Her husband Yakov was a pharmacist. I can’t remember his last name. Sonja had a traditional Jewish wedding. I went to the wedding party with my parents, and I can remember the ceremony. Sonja and her husband were standing under the chuppah, and a rabbi kept reading some prayers. I though it was very tiring and exhausting. I felt thirsty and hungry and couldn’t wait till we could sit at the table. Then finally we could enjoy the party and the delicious and plentiful food. After this hearty treatment people danced. It was a lot of fun. After the wedding Sonja moved in with her husband.

The Soviet invasion of the Baltics

In 1940 the Soviet rule was established in [Occupation of the Baltic Republics] 4 Estonia. It introduced no changes into our way of living. None of our relatives had any riches, houses or any other property. We retained our apartment in Peek Street, and my father continued working as a tinsmith. The resettlement on 14 June 1941 5 did not affect or family either. One week after the resettlement, on 22 June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union 6 without declaring a war. My father and his brothers Max, Zalman and Leo were conscripted to the Soviet army almost immediately. I remember my mother and me accompanying my father to a gathering point, and how he held me. This happened on the first days of the war. After that mama started packing so that we could evacuate. Mama had a strong mind. She knew that Jews could not stay in Estonia. Mama convinced Grandmother Teresa, her mother, to evacuate with us. My grandfather was not there with us any longer. He died in 1940 and was buried according to Jewish rules in the Jewish cemetery in Tartu. Mama was telling my grandmother’s sister Rokhe-Leya to join us, but Rokhe-Leya intended to stay. She said she was too old to travel, and she wanted to stay in Tartu. She wanted to die in Tartu and be buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tartu. Many Jews stayed in the town. Unfortunately, so many refused to evacuate. Germans killed them all. When we returned after the war, people told us that some Estonians guided Germans to Jewish houses pointing at Jews. We don’t even know where Rokhe-Leya’s grave is.

During the war

My mother, my grandmother and I left. Aunt Sonja and her husband also left their home, but apart from us. Our family arrived at Andijоn [Uzbekistan, 250 km from Tashkent, about 3500 km south-east of Moscow], a small town in Uzbekistan, and Aunt Sonja ended up in Uvel’ka town, Cheliabinsk region, in Siberia. I have very vague memories of our trip. There was a train, a barge, and then a horse-driven wagon. It was very hot, and we were thirsty, there were lots of flies and midges without number. We were accommodated in a local house in Andijon. Our landlady, an older Uzbek woman, was very kind to us. My mother found a job at a storage facility in a typhoid department of the local hospital. This job entailed a lot of risk for my mother, my grandmother and me, since we were at risk of getting the infection, but there was no alternative job for my mother. We were very fortunate to have not got the infection, however weakened we were due to the circumstances. There were numbers of people in the evacuation in Andijon. Perhaps, this number even exceeded the number of local population. We were the only ones from Estonia, though. There were numbers of people from Russia, Byelorussia and Ukraine. I picked up some Russian easily, but it was rather a challenge for my mother. However, she managed to converse, though she spoke Russian with some accent. Uzbek was more difficult for us. I also managed to pick some Uzbek playing with our landlady’s children, but Mama could never manage it. I used to go to the market with her to help her to understand the Uzbek vendors.

We were very poor then. We had hardly any luggage with us, when leaving our home. My grandmother or I could not carry much, and all we had was what my mother could carry. She had packed a change of underwear for each of us, some outer garments and food for the road. Therefore, life was even more difficult for us in the evacuation. Other people had some valuables and nicer clothing that they could trade for food. We had no valuables even before the war, and all we could count on was what my mother could earn. Actually, there was only bread that my mother received for her bread cards 7. In hospital she was provided a bowl of soup once a day. Actually, this was a cup of boiling water with some cereal, carrots and cabbage in it. This was all food my mother had, and as for her ration of bread, she brought it home. My grandmother had a smaller share than I did. My grandmother often took my ration of bread, and my mother was very angry about it. Now I understand that my grandmother was not quite herself at the time. The only feeling that overwhelmed her was her feeling hungry. Sometimes I didn’t eat my ration at once. Then I felt starved at night. This woke me up and I cried helplessly. I put little pieces of bread under my pillow to eat it at night. My grandmother discovered this trick of mine and used to steal my bread from under my pillow. I didn’t tell my mother about this feeling very sorry for my grandmother. We felt very lucky, when my mother managed to get some mill cake fodder. This was compressed sunflower oilcake, oil production wastes. Thinking about it now, I can’t imagine how we could possibly eat it, but then there was no moment of doubt for us. We added this oilcake to some boiling water before we could eat it. It caused a lot of pain in the stomach, but we ignored such details at that time. The oilcake was rather filling, though.

Our landlady supported us a lot. She sympathized with my mother knowing how hard it was for her. She addressed her using the word ‘khanum’. It’s how they address married women in Central Asia. Our landlady often came into our room saying ‘khanum, there, take your daughter with you and come and have some plov (stewed rice and meat) with us’. Whenever our landlady made plov, she always invited us to a meal. We were lucky to have met such kind people. Their support saved our life in the evacuation. I had severe vitamin deficiency. There was something wrong with my legs. I could only walk on my toes. It only passed when we returned to Estonia and I could have proper medical treatment. While in Andijon, the only thing we cared about was to survive. I used to stay in bed for weeks: I was too weak to move. It was a bit easier in summer: there were vegetables and fruit just on the ground around. I used to play out with the neighbors’ children, and we went to bathe in irrigation canals in the village.

In December 1942 we received three notifications of death. My father and his younger brothers Zalman and Leo died in a battle near Velikiye Luki, [Pskov region, Russia, about 450 km west of Moscow]. They were in the Estonian Corps 8 of the Soviet army 9. According to witnesses of these battles, they were very severe. Only my father’s brother Max returned from the war. He also served in the Estonian Corps and participated in liberating Estonia.

In due time my mother’s sister Sonja found us. She and her husband lived in Uvel’ka where many Estonians found shelter. Sonja’s husband did not go to the front due to his health condition. He worked as a pharmacist in the evacuation. They had a better life than we did. They sent us few food parcels, and this was very helpful, considering our circumstances.

After the war

In November 1944 we heard that Estonia was liberated from fascists. We could start on our way home, but we had no money to buy tickets. We had to stay where we were until 1945. By that time aunt Sonja and her husband were back home in Estonia. They sent us money to buy tickets. My mother and I headed to Estonia. My grandmother died in 1943. She actually starved to death. We buried her in the local cemetery in Andijon. I don’t even know whether it was a Jewish or a common cemetery she was buried in. I was too young to know about such things.

We arrived in Tallinn wearing ragged boots and quilt jackets. My father’s parents met us at the station. They moved to Tallinn after the war. My grandmother and grandmother were in Uvel’ka, Cheliabinsk region, in the evacuation, like Aunt Sonja and her husband, but they did not communicate. They were very friendly. This was the first time in our life that they treated us kindly. We were starved, and my grandmother invited us to eat right away. She made many delicious things, and this meal was like a feast to us. We couldn’t stop eating, and Grandmother kept bringing more food. We stayed there overnight before going to Tartu.

My mother and I would have stayed to live in Tartu, had our house been intact. However, it was ruined like many other houses in Tartu during the war. Our acquaintances gave us shelter where we stayed for some time before moving to Tallinn. My mother’s sister Sonja, her husband and their baby daughter lived in a 26 square meter room in a shared apartment 10. Sonja had to go back to work. She worked as a shop-assistant. There were no nursery schools or kindergartens available at that time. Sonja talked us into moving in with them. She wanted Mama to be a babysitter. Having no other options, we agreed.

I attended no school in the evacuation. My mother believed the war wasn’t going to last long and then I would go back to an Estonian school. This was why I went to school in 1945, when I was about to turn 10. However, there were many overage children like me at that time. In the evacuation I almost forgot the Estonian language and mama sent me to a Russian school. I met Tsylia Perelman, a Jewish girl, in the first form, and we became close friends. We are still friends with Tsylia. Tsylia was two years younger than me, but this made no barrier to our friendship. When we were in the 4th form, Edith Umova came joined our class. Tsylia had known her before. Edith’s mother used to work for Tsylia’s grandmother at some point of time. We became friends, and we still are. However, Tsylia is a closer friend to me that Edith.

I became a pioneer at school 11. I did all right at school. I wasn’t a very active pioneer. I always preferred minding my own business. I wasn’t quite sociable, when a child. I was my mama’s girl. I never liked leaving mama. I remember, when my mother managed to obtain a ticket for me to go a pioneer camp near Tartu, when I was 11 or 12. Mama could not afford to take me on vacation out of town, and she was very happy that I had this opportunity to spend some time out of the town with other children. My classmates liked having vacations in pioneer camps. My friend Edith spent each summer in a camp. So, I went there, too. It was bad for me, though there were other children, and Edith was also there. Actually, the amp was not bad, but I missed my mother so much I couldn’t stand it. After two weeks in the camp, when there was just one week left, I ran away. My mother asked me what the matter was, and I frankly explained, that everything was all right, but I couldn’t help missing her. That was it. My mother never sent me to a camp again.

In 1947 Mama married Harold Kuuzik. She met him in our shared apartment. Harold was Estonian. He was single. He liked my mother at once. My mother liked him as well. Harold was kind to me. Harold asked me whether it was all right with me, if he married my mother. That they were asking my opinion was very flattering to me. Harold was born in 1915. He was much younger than my mother. My mother, though, always looked young for her age, and this age difference was not visible. I gave my consent. They registered their marriage in a registry office, and in the evening we had a quiet dinner, with Aunt Sonja and her family participating. Harold was a cabinet maker. Our neighbors used to say he was very handy and skilled. There were few things people could buy in stores then. Harold made furniture and never lacked clients. He earned well. My mother didn’t have to go to work for 5 years after they got married. He provided for my mother and me well. The only bad thing about him was that he liked drinking. Well, actually, when he drank, he went to sleep and caused no problems. My mother and Harold had no children. One day Harold decided to build a more spacious home for us. There was an old shed in the backyard. It was abandoned, and Harold made a small two-room apartment of it. The photo of it and our family having dinner was even published in a youth newspaper.

My mother always observed Jewish traditions. We celebrated all Jewish holidays. Harold celebrated with us. My mother liked cooking Jewish food. On holidays she used to make gefilte fish, staffed goose neck, chicken broth, forshmak, tsimes 12. We celebrated holidays together with Aunt Sonja and her family. Sonja didn’t like cooking, while my mother enjoyed it. On Purim she made lots of hamantashen pies. She shared them with Aunt Sonja. My mother was a terrific cook. I learned cooking from her, and I can cook and bake many things.

We kept in touch with my father’s family. My father’s brother Max married an Estonian woman after the war. She was 20 years younger than him. They had a daughter. I don’t know whether my grandmother and grandfather accepted this marriage well, but after the war such mixed marriages became a common thing with Jews. My father’s sister Lina also got married after the war. She was 55 then. I don’t remember her husband. All I remember is that he had never been married before. They had no children. Rebecca had a daughter. Mary also had a daughter. Her name was Maja, and she was the same age with me. My father’s younger sister Bertha, whose family name was Manova, had two children: son Yakov and daughter Galina. They were about the same age with me as well.

My mother went to work at the Kommunar shoe factory. She worked at a belt conveyor for 28 years, and only after my daughter was born she agreed to quit her job.

In March 1953 Stalin died. I was in the 8th form. I remember a meeting in the conference room of our school. Our principal was telling us about the great leadership of Stalin. We were sobbing. I can remember this well. There was a terrible feeling of total confusion. We didn’t know how we were going to live on, when Stalin was not there any longer. I was growing up during the Soviet rule, and at school we were raised to be patriots of our country. There were portraits of Stalin and slogans everywhere around at school. There was a poster ‘Stalin is our teacher!’ in our classroom. We were sobbing, and this was our frank grief. This grief gradually faded away, and after the 20th Party Congress 13 we discovered that Stalin was a true beast. Had he lived longer, all Jews would have been sent out of Estonia like they did to wealthier people back in 1941 and Estonian farmers in 1948. It was only some time later that I realized that Stalin couldn’t have been unaware of what was going on, but in 1953 I had no idea of such things.

After finishing the 8th form I turned 18. I was of age and I believed that my stepfather was not bound to support me and I gad to earn my own living. Harold and Mama had a different opinion, but I firmly decided I wasn’t going to be a burden to them. I became an apprentice in the Sanhygiene store. Later it became merely a perfumery store, but at the time I went to work there, they were selling washing powder, perfumery and even some plain drugs. My apprenticeship was over after two weeks, and director of the store appointed me to the position of a shop assistant. Director of the store was my school friend Masha Stumer’s stepfather Benjamin Kitt. I must have taken some natural skills after my mother. Of course, each period of time has its own specifics. While before the war the objective of a shop assistant was to convince a customer to buy a product, after the war stores hardly offered any products whatsoever. When there was something available in the store, there were long lines forming immediately. Shop assistants had to be smart, reserved, confident and be able to put down whatever conflicts at the start. People were spending hours standing in line. They grew angry and irritant, and were always ready to snap at a shop assistant. However, they never complained of my services. My customers even left their grateful notes in our blotter book. We had continuous contests for the title of the best shop assistant in the store, and I won numerous performance awards and thanks. We also received a rise to our salary for good performance. So, each of us was stimulated to perform better. I liked my job a lot. It wasn’t always easy, though. When a supply of deficit goods was delivered to our store, there were lines forming long before our opening hour. There were even fights, when we ran out of goods, when there were still people in line expecting to get what they wanted. However, we managed all right, and there were no complaints about our performance. I worked in this store for 16 years. My aunt Sonja worked in a commission store. When she decided to quit her job, she offered me her position. I worked there 16 years before retiring.

In 1956 my maternal grandmother Ella Marjenburger died. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn. My grandfather lived 10 years longer. He lived a long life. After my grandmother died he didn’t want to live alone and his daughters took turns to accommodate and look after him. My grandfather had a number of grandsons and granddaughters from his other children, and he spent more time with them than with me. He never forgave my mother marrying his son. He believed it was her fault that his son had disobeyed his parents. For this reason he treated me differently from his other grandchildren. My grandfather died from stroke in 1966. He was buried near my grandmother’s grave.

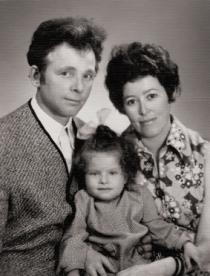

I met my husband Alexandr Speranskiy incidentally. Director of our store awarded me with a vacation in a recreation center in Iza, a resort on the Baltic Sea, for good performance. I was not very eager to go there. As I mentioned before, leaving my mother even for a short period of time was not appealing to me. However, my friends convinced me that I should go, and I decided I could live two weeks without Mama. I shared a room with a couple of ladies. We went to a café in the evening. We had coffee, ice-cream and danced. I liked dancing. I noticed a guy continuously watching me in this café. He invited me to dance and that was when we met. Alexandr and I saw each other every day. When it was time for me to leave, I told Alexandr where I worked. On my first day at work he came to see me at the end of my day. We saw each other for over three years before getting married. Alexandr was Russian, but this didn’t embarrass my mother. She liked Alexandr. Mama said he was quiet, intelligent and reliable. There have always been parents who don’t allow their children to marry people of different faith. I know few women, who are single only because their parents did not allow them to marry a Russian or an Estonian man. They spoiled their daughters’ lives of best intentions, according to how they saw it. My mother didn’t care about such things. Besides, she was married to an Estonian man as well. Alexandr and I got married in 1967, and he moved in with us.

Alexandr had a hard life. He was born in Gatchina near Leningrad, in 1933. Alexandr’s father Fyodor Speranskiy was a stableman, and his mother Anastasia Speranskaya was a laundress. Alexandr was the oldest of four children. His brother Vladimir was born in 1937, his sister Maria in 1939, and the youngest Boris in 1940. They did not join a kolkhoz 14, but lived out of the town, in a 2-storied building shared by 6 families. They had a common kitchen. They were very poor. Of all furniture they only had 2 beds: one for the parents and another one was where all children slept. Before the war Alexandr finished the 1st form. When the war began, his father was regimented to dig trenches, and before long he was conscripted to an artillery unit. He was to look after the horses that were used to pull cannons. There was a battlefield near where the family lived. They were hiding wherever they could find shelter. Having no food they were forced to pick roots and herbs. Boris, the youngest brother, was the first to starve to death. In spring 1942 Alexandr’s mother died. The children were left orphans. The house was ruined by a shell. They were wondering about the station. One day some civilians took them to a children’s home. This was a German children’s home in a 2-storied building in the outskirts of Gatchina. There was a doctor in the children’s home, and German officers used to visit it. Later they opened a school. The children were only allowed to come into the dining room, classrooms and into the bedroom. The children were provided sufficient food. Every day the doctor examined them in the presence of a German colonel. Alexandr’s sister fell ill with typhoid and died in the children’s home. In autumn 1942 Alexandr ran away. He roamed around until winter 1943, but then he came back to the children’s home. His brother told him that Germans were collecting blood from the children. There was a hospital in Gatchina, and they might have taken this blood for their wounded military. In spring 1943 the children were put on a train that headed in the direction of Pskov. They spent the summer in an abandoned mansion. There were no military, but there were 2 women looking after the children. There were partisans nearby, and one day German military came to the house looking for partisans. They chased the children away from the house. The children went to nearby villages looking for shelter. Then there came a rumor that Germans were looking for the children. The women looking after the children, found the partisans and asked then for protection. The partisans accommodated them in a village and later they took them to the children’s home in Sestroretsk. Alexandr finished the 4th form in the town. In 1947 the children were taken back to Tallinn. They were admitted to a vocational school. Alexandr was trained in the construction business and got a job assignment to the construction of a chemical enterprise in Kokhtla-Jarve. In 1950 he was transferred to the plywood/furniture factory in Tallinn to be a worker. He worked at the factory until 1952, when he was conscripted to the army. When his service was over, he became a sailor. After we got married Alexandr went to work in construction. Alexandr’s brother settled down in Nikolaev, Ukraine. He’s probably passed away, but his children still live in Ukraine.

Our only daughter was born in 1970. My pregnancy and delivery were hard on me. I was about 35, when our girl was born. We gave her the name of Marina. She was very little at birth, but she developed all right. I had to go back to work, and my mother agreed to retire and take care of Marina. Marina was a very pretty girl. She had thick heavy wavy hair with an auburn tint. When we walked in the street, her hair always drew attention. People thought I curled her hair. We adored Marina. She was the apple of our eyes. At the age of 5 she fell ill with scarlet fever, and had to take antibiotics. The girl started gaining weight. Before long we noticed that our former vivid and quick to laugh girl turned into a slow dumb girl. At that time Marina was in the first form. Initially she managed the school load, but later her teachers started complaining that she was far behind her classmates. They suggested that I took my daughter to a school for retarded children. I decided to be in no hurry in this regard and hired a teacher to give our daughter individual classes. This teacher spent a lot of time with my daughter. Gradually, my daughter’s performance at school improved, but then things grew worse. She couldn’t stay still 45 minutes in class. Her memory grew worse. I quit my job and stayed at home for 3 years to look after my daughter. She could go to school no longer. My mother helped me a lot. I can’t imagine what I would have done without her.

In 1969 our house was included in the removal plan. We received a 2-room apartment in a panel apartment house. The construction of this type of apartment houses was initiated during the Khrushchev 15 rule, and these apartments were called ‘Khrushchevka’ apartments 16. It was a small apartment. At that time the standard floor space per person was 7.5 m2. There were four of us, and when my daughter was born, it became five of us sharing this apartment. In 1976 my stepfather died. Alexandr’s company started construction of apartments for the employees having insufficient living area. Alexandr was included in the list of those in need of an apartment, and in 1989 we received a 4-room apartment. We were so happy. My mother and my daughter had a room each. Unfortunately, our happiness did not last. When Marina was 20, she was paralyzed. She was taken to a hospital where she contracted some infection. She faded away within one month. She died in December 1990. My friends were telling me to sue the hospital, but I was too weak to deal with it. It wouldn’t have given me my little girl back. My mother and my daughter were very close. My mother could not bear to live after Marina died. She died 10 months later in 1991. The grandmother was buried next to her granddaughter in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn.

My husband and I were left on ourselves in our 4-room apartment. Everything reminded us of our irreparable loss, and it became too big for the two of us. We traded it for a 2-room apartment. This is where we live now. This was a reasonable move, considering that we wouldn’t be able to pay our bills for a 4-room apartment now.

When Israel was established in 1948, I didn’t pay much attention to it. I was growing up a Soviet child, and there was nobody to influence me. I was only interested in Israel as much, as my mother’s sister Fanny living there was concerned. My attitude changed in 1964, when Fanny visited Tallinn after many years. My mother and her sister Sonja remembered her, but Sonja’s daughter Tamara and I had never seen Fanny before. We were very happy to finally reunite. We spent a lot of time together. There was never enough time for us to talk. My aunt told us about her life, her children and about life in Israel. She told such amazing things. Since then Israel became a dream country for me. I wish I could visit this country at least once to see what it is like. In 1967 my aunt sent me a letter of invitation, but Soviet authorities did not allow me to visit her. I was not married yet, and their concern was probably that I might not come back. Besides, this was when the 6-Day War 17 was on in Israel. Late, when I got married, I did not want to start thinking about the trip again. I did not consider moving to Israel. As for me, Estonia is the best country in the world, and Tallinn is the best town to live in. I just cannot imagine living elsewhere, but in Estonia. Mama was the same. She did not like leaving home for long. She became homesick. I love Tallinn. I’ve never faced any anti-Semitism. I’ve never heard a single indecent word in my regard or about Jews. This even adds to my love of the country. However, I would love to visit my historical Motherland. This is how we referred to Israel during the Soviet time. Unfortunately, this dream is never to come true, considering my health condition. I used to correspond with Aunt Fanny. Her husband died in 1992, and my aunt lived 10 years longer. Fanny died in 2002. I don’t correspond with her children. I don’t know English or Ivrit, and they speak no Russian or Estonian. My cousin Tamara, living in New York, sees them every now and then. She told me they are very nice people. She visited them in Israel and was very happy about how they received her. Tamara also told them about me.

When in the 1970s Jews were officially allowed to leave the USSR for Israel, almost all our relatives moved there. My father’s sister Rebecca and Bertha and their families moved almost immediately. When Lina’s husband died, she followed her sisters to Israel. My mother’s sister Sonja and her husband also moved to Israel. Tamara and her husband lived in the USA. Sonja’s husband died shortly after they arrived in Israel. Perhaps, the climate was not quite agreeable with him. As for Sonja, she lived many years in Israel before she died in 2000. There are only Mary and Max of my father’s kin living in Tallinn now. We hardly kept in touch with Max, but as for Mary, we saw each other. Of our family, only my cousin Maja, Mary’s daughter, and I are left. Mary died in 2001 and Max died in 1995. They were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn. My aunt Bertha lives in Israel. Rebecca died in Israel in 2000, and Lina died in 2004. We corresponded with them a lot. However, we never considered moving there. In addition to what I have already mentioned, there were two other reasons: the climate, considering that I can’t bear the heat, and the language. It’s easier for young people to learn languages, but with older people, it sometimes becomes next to impossible.

We have no living relatives left in Tallinn. There are only graves. There are many graves, and there’s only my husband and me to look after them. We often visit my mother and daughter’s graves, and all other graves as well. We clean them up. The janitor of the Jewish cemetery once said tome: whoever gets what in heritage, but you’ve got graves. This is true. We are responsible for these graves. If we ever decided to leave Estonia, they would be abandoned.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain

My life did not change much with the breakup of the Soviet Union [1991]. I was already a pensioner, and I had lived my life. It’s a good time for young people. They have their perspectives. They can go to study or work to any country and they can start a business. I have no regrets about Estonia gaining independence and choosing its own way. Well, there were many new things we had to get used to. The only thing I feel sad when thinking about it is low prices for the lodging and public services during the Soviet rule. We had these supplies almost for free, while now we have water, gas and power meters installed and have to pay for the actual quantities of our consumption. It was difficult at the start. What it was like before was that we didn’t care about how much water had been wasted. At the beginning it was quite a challenge for me to turn off a tap or gas stove. Now this has improved. People get used to many things. Our accession to the European Union did not affect our life. I don’t feel any difference. Well, actually, there are more freedoms now, and there are no stupid bans or restrictions. There is plenty of everything in stores. We are now used to this state of things, but at first, we found many things surprising. The public authorities try to support us as much as they can. We lie on two pensions and can manage more or less. Last summer those who were in the evacuation received the same benefits as those, who were subject to resettlement. This resulted in some rise in our pensions and getting some benefits. Perhaps, when we switch to Euros, this will be more challenging, but I believe the state will take care of it then.

The Jewish community of Estonia 18 was established in 1985. My mother was still with us. Gramburg, a Jewish man from Tallinn, was the head of the community. The community was just making its first steps, but their primary concern was to take care of older people. They delivered food packages, and my mother was one of those they were delivered to. Some time later Gramburg refused to lead the community. This job was too much for him. My school friend Tsylia Perelman, whose family name is Laud, replaced him. Tsylia worked in the community since the first days. She was a volunteer in the community then. She always had good organizational skills. When Tsylia became the leader and could dedicate all her efforts to the community, she made it very different for the community. Our community regained the old building of the Jewish gymnasium. There was annex and old sheds there as well. Tsylia decided to renovate these annex buildings. Now the community has its offices and a synagogue. They also started construction of a new synagogue in the yard. Tsylia improved the social services. Hot meals or food packages were delivered to older people. The service of visiting nurses also improved. Tsylia invited a rabbi to Tallinn. This position was vacant since fascists killed Abu Homer 19, the rabbi of Tallinn before the war. Since then we had a gabe, who could recite a prayer, conduct a holiday, mourning ritual or a chuppah. However, none of these gabes had special education. Our current rabbi Shmuel Kott finished a yeshivah in Israel. He likes Tallinn and our community. I believe he will stay long here.

It’s not only the food packages that our community provides. My husband is a pensioner, but he’s still full of energy and doesn’t feel like just staying home. Our community invited Alexandr to work as a janitor. They don’t pay much for this work, and his salary does not add much to our family budget. However, while he is still strong, why not work? He talks to people. Besides, he is used to physical work, and there’s not much to do at home. I believe, this job helps Alexandr to remain fit, and we are grateful to the community for giving us this chance.

We’ve always celebrated Jewish holidays. While my mother was with us, she always cooked special food for holidays and observed traditions. After my mother’s death, I took up this responsibility. I invite my friends. They are alone now. I cook meals, and we celebrate together with my friends. My husband is always with us. He knows about Jewish holidays and traditions. We also visit the community. The community members and the rabbi make all arrangements. At times I feel down and don’t feel like going out, but then I pull myself together and go visit the community. They always lift up my spirits and make me forget about depression. I watch what’s going in the Jewish life in the world. The community is so much involved in our life that I cannot imagine life without it.

Glossary:

1 Revisionist Zionism

The movement founded in 1925 and led by Vladimir Jabotinsky advocated the revision of the principles of Political Zionism developed by Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism. The main goals of the Revisionists was to put pressure on Great Britain for a Jewish statehood on both banks of the Jordan River, a Jewish majority in Palestine, the reestablishment of the Jewish regiments, and military training for the youth. The Revisionist Zionists formed the core of what became the Herut (Freedom) Party after the Israeli independence. This party subsequently became the central component of the Likud Party, the largest right-wing Israeli party since the 1970s.2 The Tartu Synagogue was built in 1903 by R

Pohlmann, architect. This Synagogue was destroyed by fire in 1944. The ritual artifacts of the Tartu Synagogue and the books belonging to Jewish societies were saved during WW II by two prominent Estonian intellectuals – Uki Masing and Paul Ariste. A part of synagogue furnishing has been preserved in the Estonian Museum of Ethnography.3 Five percent quota

In tsarist Russia the number of Jews in higher educational institutions could not exceed 5% of the total number of students.4 Occupation of the Baltic Republics (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania)

Although the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact regarded only Latvia and Estonia as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe, according to a supplementary protocol (signed in 28th September 1939) most of Lithuania was also transferred under the Soviets. The three states were forced to sign the ‘Pact of Defense and Mutual Assistance’ with the USSR allowing it to station troops in their territories. In June 1940 Moscow issued an ultimatum demanding the change of governments and the occupation of the Baltic Republics. The three states were incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republics.5 Deportations from the Baltics (1940-1953)

After the Soviet Union occupied the three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) in June 1940 as a part of establishing the Soviet system, mass deportation of the local population began. The victims of these were mainly but not exclusively those unwanted by the regime: the local bourgeoisie and the previously politically active strata. Deportations to remote parts of the Soviet Union continued up until the death of Stalin. The first major wave of deportation took place between 11th and 14th June 1941, when 36,000, mostly politically active people were deported. Deportations were reintroduced after the Soviet Army recaptured the three countries from Nazi Germany in 1944. Partisan fights against the Soviet occupiers were going on all up to 1956, when the last squad was eliminated. Between June 1948 and January 1950, in accordance with a Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR under the pretext of ‘grossly dodged from labor activity in the agricultural field and led anti-social and parasitic mode of life’ from Latvia 52,541, from Lithuania 118,599 and from Estonai 32,450 people were deported. The total number of deportees from the three republics amounted to 203,590. Among them were entire Lithuanian families of different social strata (peasants, workers, intelligentsia), everybody who was able to reject or deemed capable to reject the regime. Most of the exiled died in the foreign land. Besides, about 100,000 people were killed in action and in fusillade for being members of partisan squads and some other 100,000 were sentenced to 25 years in camps.6 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.7 Card system

The food card system regulating the distribution of food and industrial products was introduced in the USSR in 1929 due to extreme deficit of consumer goods and food. The system was cancelled in 1931. In 1941, food cards were reintroduced to keep records, distribute and regulate food supplies to the population. The card system covered main food products such as bread, meat, oil, sugar, salt, cereals, etc. The rations varied depending on which social group one belonged to, and what kind of work one did. Workers in the heavy industry and defense enterprises received a daily ration of 800 g (miners - 1 kg) of bread per person; workers in other industries 600 g. Non-manual workers received 400 or 500 g based on the significance of their enterprise, and children 400 g. However, the card system only covered industrial workers and residents of towns while villagers never had any provisions of this kind. The card system was cancelled in 1947.8 Estonian Rifle Corps

military unit established in late 1941 as a part of the Soviet Army. The Corps was made up of two rifle divisions. Those signed up for the Estonian Corps by military enlistment offices were ethnic Estonians regardless of their residence within the Soviet Union as well as men of call-up age residing in Estonia before the Soviet occupation (1940). The Corps took part in the bloody battle of Velikiye Luki (December 1942 - January 1943), where it suffered great losses and was sent to the back areas for re-formation and training. In the summer of 1944, the Corps took part in the liberation of Estonia and in March 1945 in the actions on Latvian territory. In 1946, the Corps was disbanded.9 Soviet Army

The armed forces of the Soviet Union, originally called Red Army and renamed Soviet Army in February 1946. After the Bolsheviks came to power, in November 1917, they commenced to organize the squads of worker’s army, called Red Guards, where workers and peasants were recruited on voluntary bases. The commanders were either selected from among the former tsarist officers and soldiers or appointed directly by the Military and Revolutionary Committy of the Communist Party. In early 1918 the Bolshevik government issued a decree on the establishment of the Workers‘ and Peasants‘ Red Army and mandatory drafting was introduced for men between 18 and 40. In 1918 the total number of draftees was 100 thousand officers and 1.2 million soldiers. Military schools and academies training the officers were restored. In 1925 the law on compulsory military service was adopted and annual drafting was established. The term of service was established as follows: for the Red Guards- 2 years, for junior officers of aviation and fleet- 3 years, for medium and senior officers- 25 years. People of exploiter classes (former noblemen, merchants, officers of the tsarist army, priest, factory owner, etc. and their children) as well as kulaks (rich peasants) and cossacks were not drafted in the army. The law as of 1939 cancelled restriction on drafting of men belonging to certain classes, students were not drafted but went through military training in their educational institutions. On the 22nd June 1941 Great Patriotic War was unleashed and the drafting in the army became exclusively compulsory. First, in June-July 1941 general and complete mobilization of men was carried out as well as partial mobilization of women. Then annual drafting of men, who turned 18, was commenced. When WWII was over, the Red Army amounted to over 11 million people and the demobilization process commenced. By the beginning of 1948 the Soviet Army had been downsized to 2 million 874 thousand people. The youth of drafting age were sent to the restoration works in mines, heavy industrial enterprises, and construction sites. In 1949 a new law on general military duty was adopted, according to which service term in ground troops and aviation was 3 years and in navy- 4 years. Young people with secondary education, both civilian and military, with the age range of 17-23 were admitted in military schools for officers. In 1968 the term of the army service was contracted to 2 years in ground troops and in the navy to 3 years. That system of army recruitment has remained without considerable changes until the breakup of the Soviet Army (1991-93).10 Communal apartment

The Soviet power wanted to improve housing conditions by requisitioning ‘excess’ living space of wealthy families after the Revolution of 1917. Apartments were shared by several families with each family occupying one room and sharing the kitchen, toilet and bathroom with other tenants. Because of the chronic shortage of dwelling space in towns communal or shared apartments continued to exist for decades. Despite state programs for the construction of more houses and the liquidation of communal apartments, which began in the 1960s, shared apartments still exist today.11 All-Union pioneer organization

a communist organization for teenagers between 10 and 15 years old (cf: boy-/ girlscouts in the US). The organization aimed at educating the young generation in accordance with the communist ideals, preparing pioneers to become members of the Komsomol and later the Communist Party. In the Soviet Union, all teenagers were pioneers.12 Tsimes

Stew made usually of carrots, parsnips, or plums with potatoes.13 Twentieth Party Congress

At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin’s leadership.14 Kolkhoz

In the Soviet Union the policy of gradual and voluntary collectivization of agriculture was adopted in 1927 to encourage food production while freeing labor and capital for industrial development. In 1929, with only 4% of farms in kolkhozes, Stalin ordered the confiscation of peasants' land, tools, and animals; the kolkhoz replaced the family farm.15 Khrushchev, Nikita (1894-1971)

Soviet communist leader. After Stalin’s death in 1953, he became first secretary of the Central Committee, in effect the head of the Communist Party of the USSR. In 1956, during the 20th Party Congress, Khrushchev took an unprecedented step and denounced Stalin and his methods. He was deposed as premier and party head in October 1964. In 1966 he was dropped from the Party's Central Committee.16 Khrushchovka

Five-storied apartment buildings with small one, two or three-bedroom apartments, named after Nikita Khrushchev, head of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death. These apartment buildings were constructed in the framework of Khrushchev’s program of cheap dwelling in the new neighborhood of most Soviet cities.17 Six-Day-War: The first strikes of the Six-Day-War happened on 5th June 1967 by the Israeli Air Force. The entire war only lasted 132 hours and 30 minutes. The fighting on the Egyptian side only lasted four days, while fighting on the Jordanian side lasted three. Despite the short length of the war, this was one of the most dramatic and devastating wars ever fought between Israel and all of the Arab nations. This war resulted in a depression that lasted for many years after it ended. The Six-Day-War increased tension between the Arab nations and the Western World because of the change in mentalities and political orientations of the Arab nations.

18 Jewish community of Estonia – on the 30th of March 1988 the meeting of Jews of Estonia consisting of 100 people, convened by David Slomka, made a resolution to establish community of Jewish Culture of Estonia (KJCE) and in May 1988 the community was registered in Tallinn municipal Ispolkom. KJCE was the first independent Jewish cultural organization in USSR to be officially registered by the Soviet authorities. In 1989 first Ivrit courses were opened up, although the study of Ivrit was equaled to Zionist propaganda and was considered to be anti-Soviet activity. The contacts with Jewish organizations of other countries were made. KJCE was the part of Peoples’ Front of Estonia, struggling for state independence. In December 1989 the first issue of KJCE paper Kashachar (Dawn) was released in Estonian and Russian languages. In 1991 the first radio program about Jewish culture and activity of KJCE ‘Sholom Aleichem’ came out in Estonia. In 1991 Jewish religious community and KJCE had a joined meeting, where it was decided to found Jewish Community of Estonia.