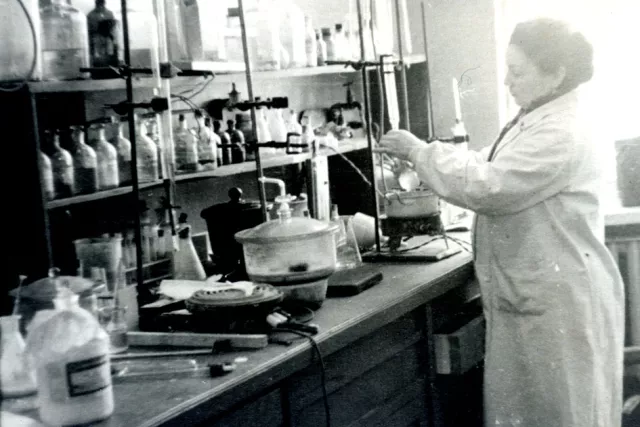

This photograph was taken in 1960 in Leningrad. It shows me in the chemical laboratory. Here I’ll tell you how I became a chemist.

I finished ten-year secondary school in Gomel and got only excellent marks. Having got excellent school-leaving certificate pupils were exempt from entrance examinations. I sent my documents to the Leningrad Technological College and became a student of the chemical department.

I finished 2 courses, and the war burst out. On July 19, 1942 the College was evacuated to Kazan, we studied and worked there. Some faculties organized production of saccharin.

As for me, I worked at the faculty of pyrotechnics; there we were engaged in getting of phosphorus. It was a harmful and dangerous process.

Every day I received a small amount of butter and 2 spoons of granulated sugar. It supported my organism a little.

In general, we lived in poverty. For dinner they gave us 2 spoons of mashed peas (we liked it very much). We added there an onion and ate it with a piece of brown bread.

We received worker's cards, therefore it was impossible to die having 800 g of bread a day. Every Sunday together with my friend we went to the market and bought half a kilogram of potatoes, boiled it, ate and drank the water.

Till now I can't permit myself pouring out water, where I had boiled potatoes. So, we lived that way, but it couldn't be helped! In Leningrad people starved more. We knew it for sure, because a lot of us had relatives there…

Winters were very hard in Kazan. And we had almost no clothes to put on. The Kazan girls had valenki. [Valenki - winter boots made of milled wool.] And so we wore those valenki by turns. I was lucky: I had a winter coat with me.

When we were at the railway station going to leave for Kazan, my mother-in-law almost threw it in my hands by force.

I remember that I was very indignant at it 'It is summer now, the war will be finished in 3 or 4 months, why should I take it with me?'

And she answered 'If you don't need it, give it somebody as a present. And now take it please, don't refuse, do as I ask you.' So I took it, because it would have been in bad taste to refuse.

Till now I cannot understand, how she managed to find me that day at the overcrowded railway station. She also brought me a wadded blanket.

It is incumbent upon me to mention that in Kazan we were received very well, though a lot of colleges were evacuated there. We never heard a word of reproach, while in fact not everywhere evacuated people were met affably.

We were lodged in the large basement of Kazan Chemical and Technological College. They placed there a hundred beds and a hundred bedside-tables. It was very warm there, that's why I did not unpack my blanket.

In 1943 or 1942 they sent us to dig entrenchments [during the war all people able to work were mobilized for earthwork construction around the cities].

At that moment I called my blanket to mind and took it with me. We were lodged in a premise with an earthen floor and I decided to unpack my blanket.

I undid the package and saw a blanket in a snow-white blanket cover. And you see, the blanket cover was beautifully embroidered.

Well, the girls saw it and immediately nicknamed me Countess Balonova. They called me Countess all the time we were together.