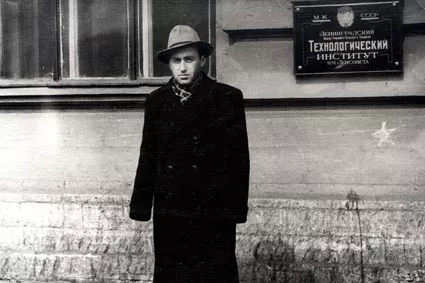

Igor Lerner

This photograph taken in 1954 shows me near the Leningrad Technological College. It was my fellow-student who photographed me. Here I’ll tell you what difficulties I had to overcome to become a student.

In fact I studied in the 10th class not long (before the beginning of the war) and received a paper about finishing school. But it was not a school-leaving certificate of official standard. And I had a dream to receive higher education. After 5 years in Austria I came back to Leningrad. I managed to retire only with assistance of the chief of our political department.

My family members were friends with Natalya Sergeevna Michurina, my former teacher of history. My father was a shop director and helped her with food. She worked as a teacher at the Pedagogical College. I told her that I would like to become a student of her College. She answered that it was impossible without a school-leaving certificate and I had to go to Moscow and change my paper for the certificate. I did not want to go there (I realized that I forgot everything during 8 years of my military service). Therefore I decided to enter the 10th class of an evening school. [Evening schools in the USSR were institutions of general educational for working people.] I became a schoolboy again, but they made it imperative that I should be employed.

Here my tortures started. About 2 months I ate nothing and could not sleep: I tried to find job, but they looked into my passport, saw the item 5 and used to say the following: 'No vacancy'. They did not permit me to become even a pupil of metalworker at a factory. But I was a very good rifleman: during the war they used to invite me to adjust captured weapon. At last I got fixed up in a job of shooting club instructor. I finished my school with a medal, i.e. I had the right to enter a college without entrance examinations (it was necessary only to pass an entrance interview.) I decided to enter the College for film-engineers.

I called them and asked if they took in medal winners. They said yes, I came and showed my documents. They said 'You know, we have no vacancies'. The same happened in many other colleges. One day I called a college entrance examination from telephone box situated close to the College door. They said 'Come to us please!' I appeared 5 minutes later and heard the following: 'Sorry, we have no vacancies'. At last I decided to make no more telephone calls and went to the Technological College. [The Technological College prepared specialists in the chemical sphere]. I showed them my documents 'You won't take me in, will you?' - 'Why? Leave your documents here and come tomorrow morning'. I came next morning, and they said 'You are accepted, but it is provisional. Tomorrow come to take part in the entrance interview'. Having come for the interview, I found out that all medal-winners were Jews.

So I became a student of the Technological College. I graduated from it with excellent marks. Besides I was an editor of the College newspaper, a former front-line soldier, a communist party member. Therefore notwithstanding the generally accepted mandatory job assignment, they suggested me to choose a place where I would like to work. There were 2 good places to work at and one of them was GIPH (the State Institute of Applied Chemistry). Everyone knew that at GIPH they never employed Jews, therefore I chose the 2nd one (not to receive refusal!). And what a surprise: I got to know that they invited me to GIPH! 2 weeks later I started working there. My first chief was a Jew, too. There I worked 42 years (from 1956 till 1998). I liked my work and was one of the top experts of my profession. My first position was a mechanic of experimental workshop. Later I became its chief and worked till I retired on pension. Nobody forced me to retire, on the contrary: they tried to persuade me to go on working.